KEY TAKEAWAYS

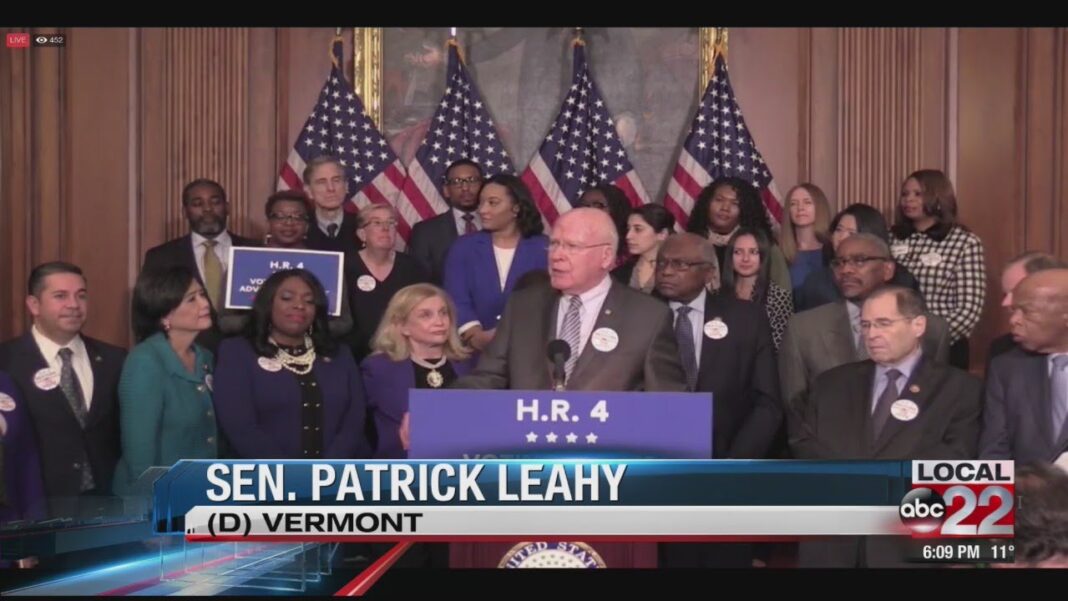

- In the latest attempt to amend the Voting Rights Act, Senator Patrick Leahy (D., Vt.) recently introduced the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

- The real aim is to reverse the 2013 SCOTUS decision in Shelby County v. Holder and to give the political allies of Democrats control over state election rules.

- The Leahy bill is unjustified and unneeded, and would be a dangerous violation of state sovereign

In the latest attempt to amend the Voting Rights Act, Senator Patrick Leahy (D., Vt.) recently introduced the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. It sounds great until you realize it will be used to achieve partisan political gains rather than prevent racial discrimination.

The real aim is to reverse the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder and to give the political allies of Democrats—the radicals who inhabit the career ranks of the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Justice Department (where I used to work), and advocacy groups such as the ACLU—control over state election rules.

It is a dangerous bill that violates basic principles of federalism. It also illustrates what could happen if Democrats gain control of Congress and the White House, to the detriment of secure, fair elections administered by the states.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) is probably one of the most successful pieces of legislation ever passed by Congress. It helped eliminate the widespread discriminatory practices that were preventing African Americans from registering and voting in the 1960s. There are no longer any such barriers or practices that block black Americans (or anyone else) from registering and voting, despite the mythical claims of “voter suppression” promulgated by the Left. In the 2012 presidential election, for example, blacks voted at a higher rate than whites nationally (66.2 percent vs. 64.1 percent), according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The main provision of the VRA is Section 2, which prohibits any voting “standard, practice or procedure . . . which results in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color” or membership in certain language-minority groups. It is permanent, applies nationwide, and can be enforced by the Justice Department as well as private parties. It was also completely unaffected by the Shelby County decision and remains in full force today.

Shelby County was—and the Leahy bill is—about another provision in the VRA: Section 5. Section 5 was originally an emergency five-year provision that required “covered” jurisdictions to get preapproval of any changes in their voting laws and practices (even simple changes such as the location of a polling place) from the U.S. Department of Justice or a federal court in Washington, D.C., a process known as “preclearance.” Section 5 was renewed for an additional five years in 1970; for an additional seven years in 1975; for an additional 25 years in 1982; and finally for an additional 25 years in 2006. At the time of the Shelby County decision in 2013, Section 5 covered nine states and parts of six others.

Shelby County dealt specifically with Section 4 of the VRA, which determined the states and smaller jurisdictions that were subject to Section 5 preclearance. The coverage formula was based on a jurisdiction’s having voter registration and turnout by all voters of less than 50 percent in the 1964, 1968, or 1972 elections. The formula was designed to capture states engaging in blatant discrimination by taking into account black voters’ low registration and turnout caused by those discriminatory practices.

Congress did not update the coverage formula in 2006. Why not? Perhaps because, if it had, all of the covered jurisdictions—mostly (but not exclusively) southern states—would have dropped out of the Section 5 preclearance requirement owing to the vast improvement of voting conditions since 1972. By 2006, the registration and turnout rates of black voters were on par with or even exceeded those of white voters in many of the covered states. So states such as Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi remained under the onerous preclearance requirement based on information that was almost 40 years out of date.

But the Left loved Section 5 because of the central role played in its enforcement by its friends and political allies in the career ranks of the Civil Rights Division, many of whom were hired from the ACLU, the NAACP, and other groups allied with the Democratic Party. They could easily refuse to preclear any voting change opposed by the Left—such as voter-ID laws—without having to go to court with a Section 2 lawsuit, where they would have to prove that a law was discriminatory.

The Supreme Court ruled that Section 5 was unconstitutional because it had not been updated in 2006 to reflect modern conditions. The Supreme Court said, “History did not end in 1965, . . . yet the coverage formula that Congress reauthorized in 2006 . . . ke[pt] the focus on decades-old data relevant to decades-old problems, rather than current data reflecting current needs.”There’s another reason Section 5 preclearance was needed. Prior to 1965, states were actively evading federal-court decrees ordering them to stop discriminatory practices. And the only way a state could overcome an objection by the Justice Department was to file a lawsuit in the District of Columbia—no other federal court—because Congress did not trust federal judges in the southern states to enforce the VRA.

According to the Supreme Court in Shelby County, because Section 5 blatantly invades state sovereignty over elections, Congress would, in order to justify its continuation, have to show that there were still “blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees,” “voting discrimination on a pervasive scale,” or “flagrant” or “rampant” voting discrimination. None of that was present in 2013 when the case was before the Supreme Court, and there is no evidence of such behavior today, either.

Yet the Leahy bill would reimpose the Section 5 preclearance based on a new coverage formula even more onerous than the prior one and keep the D.C.-court requirement as if it were still 1965. States would be covered in their entirety for ten years if the attorney general determined that ten “voting-rights violations” occurred during a 25-year period, even if the state was responsible for only one of them and the rest were committed by city or county governments over which the state had no authority.

Voting-rights violations would include objections made by the attorney general, which don’t require any finding of intentional discrimination. A claimed discriminatory effect based purely on a statistical disparity would count as a violation. Such “disparate impact” liability has been misused in many areas besides voting. The Justice Department has a troubling history under Section 5 of making unwarranted objections and being castigated by courts for its behavior, as evidenced by a 2012 federal-court decision overturning the DOJ’s frivolous objection to South Carolina’s voter-ID law.

Consent decrees and lawsuit settlements would also count as voting-rights violations. This would provide an incentive for the Justice Department and advocacy groups to file as many lawsuits as possible against states, even if they had little or no merit, in order to obtain quick settlements that could then be used to trigger preclearance coverage.Certain voting changes would automatically trigger preclearance requirements for jurisdictions. These would include any change in political boundaries during redistricting that resulted in reducing the population of a particular racial-minority group by three or more percentage points. They would also include any change requiring “proof of identity to vote” or “proof of identity to register to vote,” as well as any “change that reduces, consolidates, or relocates voting locations” in jurisdictions with a certain minimum percentage of minority voters. This is an obvious attempt to outlaw state voter-ID requirements.

In addition, the Leahy bill would make it almost impossible for any state or local jurisdiction to defend itself against a lawsuit filed by the Justice Department or an advocacy group such as the ACLU. It would create a unique and novel legal standard for injunctive relief. Courts would be directed to grant an injunction under the VRA if the plaintiff had “raised a serious question”—as opposed to providing actual evidence—about whether the challenged voting change violated the VRA or the Constitution. This is like requiring a defendant in a criminal case to prove his innocence because the government simply claims he violated the law.

Since the Shelby decision, there has been a false clamor about a supposed loss of voting rights. That is a myth created by the Left and abetted by the media. That myth has been perpetuated as a way of opposing reforms intended to improve the integrity of the election process, such as voter-identification requirements and the cleanup of statewide voter-registration lists, and to justify the reimposition of federal control over state election procedures by reviving the Section 5 preclearance requirement.

There is no voter-suppression epidemic. Americans today have an easier time registering and voting than at any time in our nation’s history. On the increasingly rare occasions when discrimination actually occurs, Section 2 of the VRA provides a more than adequate remedy. The Leahy bill is unjustified and unneeded, and would be a dangerous violation of state sovereignty.

This piece originally appeared in National Review on October 15, 2020

About Hans von Spakovsky

Election Law Reform Initiative and Senior Legal Fellow, Hans von Spakovsky is an authority on a wide range of issues—including civil rights, civil justice, the First Amendment, immigration.