Franklin Delano Roosevelt is one of the most lauded and adored of the U.S. Presidents. His charming personality and fireside chats are an inseparable part of the 1930s and 40s. He pulled the country out of a depression, granted jobs to millions, and guided the United States to victory in World War II. Or did he? Only when we dig for the facts do we really see how many people were wrong about Roosevelt. Quite wrong.

“I am opposed to any dole”

Before the 1932 Democratic Convention, a poll showed that F.D.R. was the choice candidate of bank presidents and corporation directors. Roosevelt, former governor of New York, had many friends on Wall Street. During the presidential campaign F.D.R. arranged (if elected) to initiate the National Recovery Administration in return for the backing of big business (Wall Street).

As he campaigned, Roosevelt criticized Republican President Herbert Hoover’s management of the Great Depression. Roosevelt complained about Hoover’s “excessive spending” saying: “We are spending altogether too much money for government services that are neither practical nor necessary. . . . We are attempting too many functions. We need to simplify what the federal government is giving to the people.” F.D.R. whined about growing piles of “bureaus and bureaucrats” and stated firmly “I am opposed to any dole.” None of these statements seemed to make any difference during his own presidency.

Once officially the president-elect, Roosevelt became authoritative and careless. In response to an important question from the press, F.D.R. brushed it off with “That’s not my baby.” And though Hoover was still in office, Roosevelt was already taking charge of the Democratic Congress, guiding them to oppose legislation Hoover needed.

The New Deal

Author Eugene Lyons makes the point in The Herbert Hoover Story that in 1932 the people “voted against Hoover and for Roosevelt overwhelmingly, but they certainly did not vote for the New Deal. Indeed, if words have any meaning, if election speeches are anything more than trickery, they voted against the New Deal.” A “new deal” is exactly what the people got. In fact, the term comes from a Mark Twain novel: “When six men out of a thousand crack the whip over their own fellows’ backs, then what the other nine hundred ninety-four dupes need is a new deal.” By the end of Roosevelt’s twelve-year presidency, the question was, who was cracking the whip over whom? Roosevelt’s postmaster general, James Farley, would say in reference to F.D.R., “He was more popular than the New Deal itself.”

Happy Days are Here Again

With Franklin D. Roosevelt in the White House, the Democrats made it clear that they were the ones who were going to get America out of the depression—unlike Hoover who, they said, had done nothing to help the people. (F.D.R. would later refer to the depression as “the mess that was dumped in our laps.) The Roosevelt administration despised Hoover so much, they took away his Secret Service protection; they also renamed Hoover Dam, calling it Boulder Dam instead. At the same time Roosevelt attempted to stay in the good graces of liberal Republicans, placing three in his Cabinet.

Roosevelt wielded his power with a flourish. “There is not a single power I have that Hoover and Coolidge did not have,” he remarked. Says Eugene Lyons: “Roosevelt scored magnificently as a showman. He rallied mass sympathy and provided a three-ringed circus. Jovially, almost as if it were an ingenious solution of all problems, he reconciled the country to a ‘permanent emergency’.” Before long F.D.R. had charmed the nation into following his every whim. One of the first things he did was to abandon the gold standard. He used the veto 635 times; only nine times did Congress override his veto. In 1937 there was a bad recession which Roosevelt blamed on businessmen. Ironically, in spite of the Democrat’s song “Happy Days are Here Again”, unemployment continued to climb. Roosevelt merely continued to paint a picture of prosperity and pose as a champion of the people. He fooled many.

Big Government Takes Over

Roosevelt began pumping out various government agencies and programs with what seemed like every possible arrangement of the letters of the alphabet: F.E.R.A., C.W.A., N.I.R.A., W.P.A., P.W.A., N.R.A., N.L.R.B., A.A.A., C.C.C., T.V.A.—several of which were later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. For an example of what one of these programs accomplished, take the W.P.A. (Works Progress Administration). This was a program for the unemployed that put 8,500,000 people to work for a whopping $11,000,000,000. According so some New Deal critics, the W.P.A. was also rumored to stand for “We Putter Around.”

Earlier Roosevelt had been “opposed to any dole.” Now he led people to believe deficits were investments in human welfare. Between 1933 and 1936 the federal government doled $3,694,000,000. Hoover was sickened. “Upon coming into office the New Deal Administration claimed that millions of people were starving and that nothing had been done in the way of real relief,” Hoover said. “Had that been true, they would not have failed to say so during the presidential campaign [of 1932]. It would have been the best possible vote getter.”

World War II

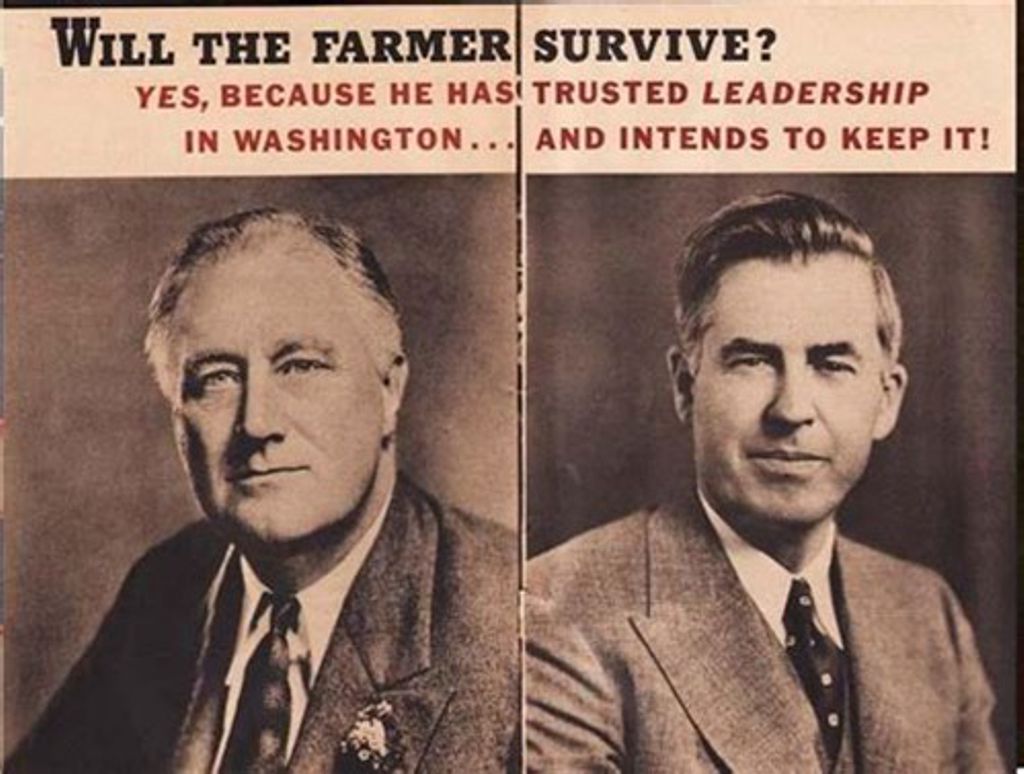

Now we come to another chapter of the Roosevelt era, that of the second world war. In the 1940 election, Democratic party bosses pressured F.D.R. to decry the idea of America’s entering the war because Republican candidate Wendell Wilkie was garnering support with such a stance. As a result, Roosevelt gave a speech, pumping up the emotions of crowds with “I have said this before, but I will say it again and again and again: ‘Your boys are not going to be sent into foreign wars!”

In the latter half of November 1941, President Roosevelt knew a Japanese fleet was at sea and that an attack on American soil was probable. (The U.S. had already broken the Japanese code.) Pearl Harbor was attacked shortly after; America went to war. Near the end of his presidency President Roosevelt would have the F.B.I. investigate prominent persons who opposed America’s entering World War II. And at the end of 1944, Roosevelt instructed the executive departments and certain agencies not to make public announcements indicating an early end of World War II. These facts make it appear that the Democrats wished not only to enter the war, but prolong it.

Regarding the atomic bomb, Roosevelt was aware of the project as early as 1939. Not even Vice President Truman knew about it until he was sworn in as President following F.D.R.’s death in 1945. Thus, the bomb could have been used much earlier on in the war, avoiding a tremendous loss of life. And despite the beliefs of many, the war, not Roosevelt, rescued the nation from the depression. It stepped up production and provided real jobs for the 4,000,000 Americans still unemployed on Pearl Harbor Day.

Communism in the Roosevelt White House

During the Roosevelt era, rumors flew that the President had Communist sympathies. In 1940 the newspapers were saying that electing Roosevelt for a third term would be “the end of free elections.” William Randolph Hearst of the Journal labeled Roosevelt and some of the President’s cronies as Communists, and spoke of the “Red New Deal.” Meanwhile, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was an active supporter of the American Youth Congress which later identified with Communism.

During the 1944 presidential campaign Republican candidate Thomas Dewey charged that F.D.R. had sold himself over to the Communists in order to stay in office. The Communist-dominated Political Action Committee (P.A.C.) had been organized to re-elect Roosevelt in 1944. This committee played a major role in the election persuading voters to choose Roosevelt for a fourth term. The P.A.C.’s chairman, Sidney Hillman, was so powerful that he “approved” the vice-presidential choice (Truman).

F.D.R. vs. Supreme Court

Another highlight of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency was his cuffuffle with the Supreme Court. President Roosevelt believed the party in power could control the court, and was irritated when much of his legislation was branded as unconstitutional. He knew his administration would be sapped of power this way. To combat this he lobbied for an increase of nine to fifteen Supreme Court justices. This way he could “pack” the court with justices who would sanction his agenda. The plan never became reality. However, by this time the conservatives on the bench caved in and began validating Roosevelt’s programs. Some said it was a defeat; Roosevelt marked it as a victory.

“… Again and again and again!”

Roosevelt occupied the White House from 1933 to 1945, being elected four times. It was soon after he took the oath of office for the second time that a reporter asked F.D.R. whether he would run for a third term. The President’s undignified answer was: “Put on a dunce cap and stand in the corner.” Roosevelt was approached with the same question two years later. “Of course I will not,” he responded. Later the war in Europe changed his mind, he explained; Roosevelt announced he had put aside “all private plans” to “offer himself” as a candidate in 1940. When the next election year (1944) rolled around, no one seemed to consider replacing Roosevelt. “I am glad to be here on this election day again,” he beamed, “and I might say again and again and again!” One wonders how many times he planned to run had he lived longer. He seemed undefeatable.

On April 12, 1945, F.D.R. died, bringing an end to one of the most powerful presidencies in U.S. history. Franklin Roosevelt’s administration redefined the powers of the presidency at a whole new level—that of the federal government.

Bibliography:

Lorant, Stefan. The Presidency. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952.

Lyons, Eugene. The Herbert Hoover Story. Washington, D.C.: Human Events, 1959.

The New Encyclopedia Britannica, 15th edition. University of Chicago, 1989.

Taylor, Tim. The Book of Presidents. New York: Arno Press, 1972.