Let’s face it. The marriage of superpowers looked great on paper. Globalists and free market proponents, seeking earnings growth and the prospects of slowly democratizing the People’s Republic of China, eagerly arranged it. The courtship began in 1972 when Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger first set foot on the soil of China’s 4,000-year-old nation. The relationship then blossomed for decades, culminating in the 2008 story-book wedding, the Beijing Summer Olympics. American sponsors Coca-Cola, General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, McDonald’s, Nike, and Visa, as well as athletes like LeBron James and Michael Phelps, arrived with great fanfare to represent our nation’s nuptial commitment to China. Hollywood’s presence was absent, but that was to be short-lived.

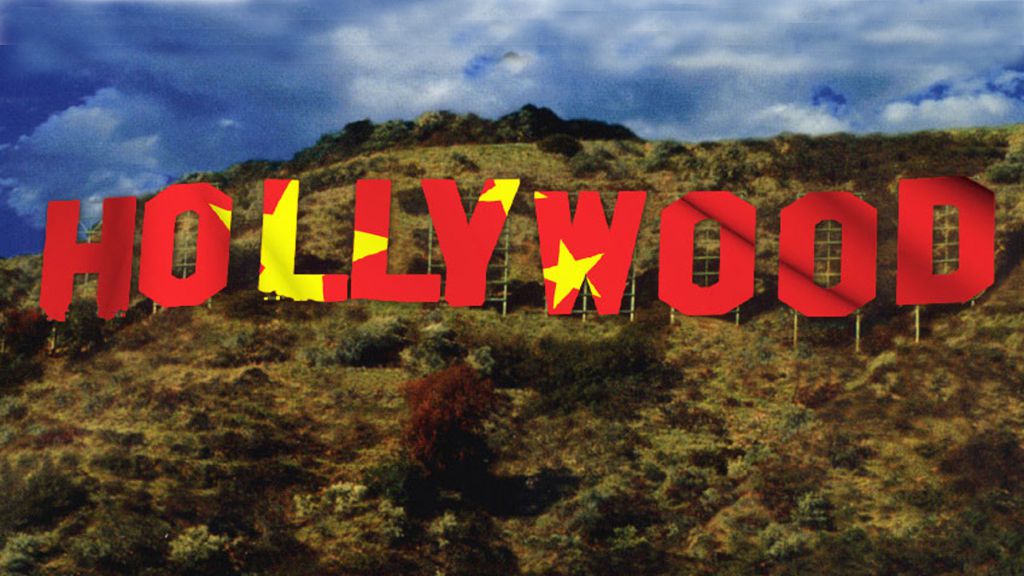

Though many of our great nation’s companies and athletes, particularly from the NBA, had substantial histories with China by that point, the movie studios had not. After those Summer Games ended, China’s Communist Party prioritized the growth of various industries, aiming to boost their middle class. The film industry was one of those, and Hollywood jumped in. China soon had 5,000 movie screens, and they multiplied dramatically over the next decade to the more than 70,000 today. Hollywood’s share of China’s box office riches followed similar course.

Other American companies in various industries experienced identical growth trajectories. China’s 1.4 billion customers were just as hungry for world-class movies as they were for Buicks, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Starbucks. Even better, consumers absorbed the soft power influence of aspirational democratic values and principles emanating from each product, though none could compare to the stories produced by our fabled studios. Movies, by far, were the strongest and most engaging form of Western propaganda. The CCP understood that. To them, movies weren’t just a product of commercial exchange. They were also a vehicle for cultural exchange. Films mixed the two evenly and potently.

By Chris Fenton