Tariffs are a component in the toolkit Trump is using to achieve his goal of restoring domestic manufacturing, experts say.

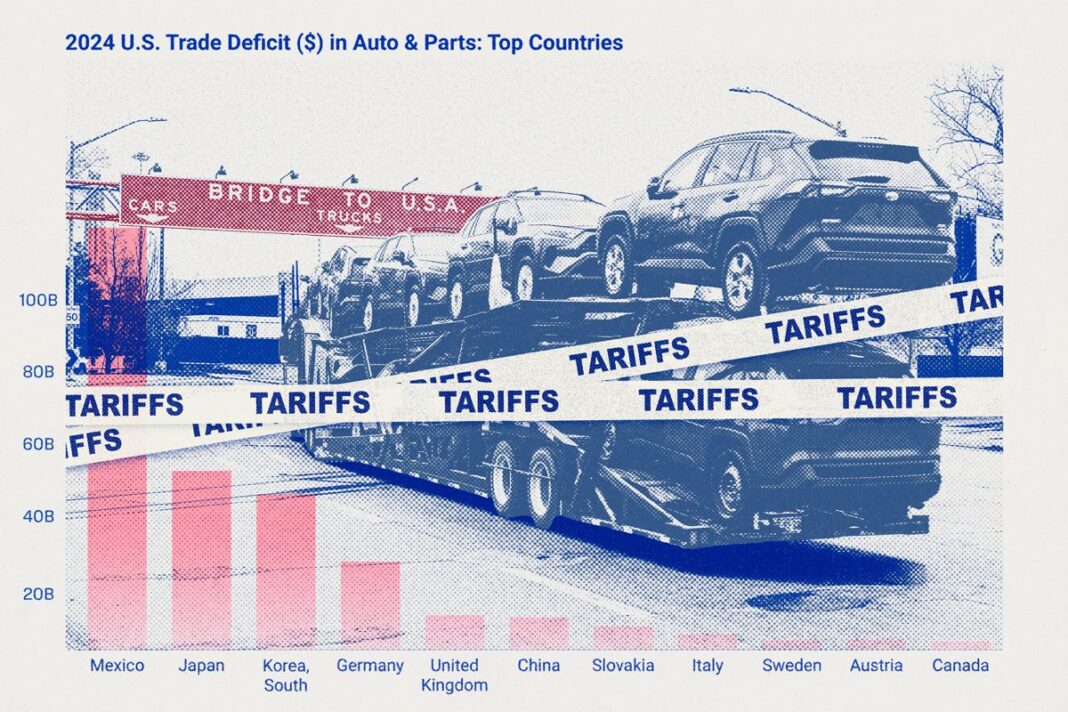

The U.S. trade deficit reached a record high of more than $1.2 trillion in 2024. Automobiles and parts accounted for nearly a quarter of that.

In a bid to reverse the trade imbalance, President Donald Trump in February introduced a plan to impose reciprocal tariffs to “level the playing field” on trade and address what his administration called unfair trade practices imposed by other countries.

The tariffs are set to go into effect on April 2, after officials determine the individual tariff rate for each country.

Trump has repeatedly highlighted the automobile industry as a potential sector for tariffs.

Automakers in the United States have undergone a rollercoaster ride since Trump announced a universal 25 percent tariff on Canadian and Mexican imports in February.

Ultimately, the auto industry obtained a one-month exemption after the big three automakers—Stellantis, Ford, and General Motors—spoke to Trump over the phone. However, this reprieve won’t shelter them from the impending reciprocal tariffs.

When announcing the exemption, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said the president expected automakers to start moving production to the United States.

“He told them that they should get on it, start investing, start moving, shift production here to the United States of America, where they will pay no tariff,” she said on March 5. “That’s the ultimate goal.”

How Did the US Get Here?

At the heart of the United States’ chronic trade deficit are countless businesses that have moved manufacturing outside the United States because of high labor costs in the country, said Yao-Yuan Yeh, professor of international studies at the University of St. Thomas in Houston.

When overseas businesses ship manufactured goods to sell in the United States, such imports usually incur a net trade deficit because the value of the goods bought will far exceed those sold.

Take the example of the auto industry.

Over the years, the sector has arranged its supply chain to take advantage of cheaper resources in other countries. According to the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association, auto parts may cross national borders as many as eight times before final assembly.

As a result, the imbalance between domestic and foreign investments shows up in the trade deficit tallies.

In 2024, automobiles and auto parts contributed $274 billion to the total U.S. trade deficit.

Nearly half of the negative balance in auto industry trade is from Mexico ($117 billion), which is followed by Japan ($50 billion) and South Korea ($43 billion). China ranked sixth in terms of its auto industry trade surplus with the United States at $9 billion, while Canada ranked 11th at $2 billion.

By Terri Wu