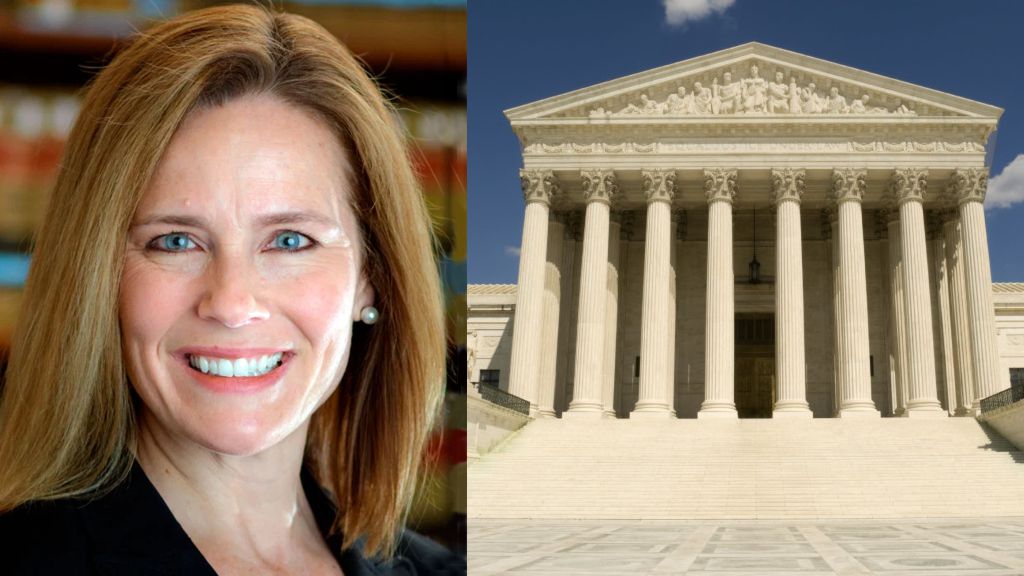

President Donald Trump nominated a woman, Amy Coney Barrett, to fill the vacancy left by the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Judge Amy Coney Barrett is a judge on the Chicago-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit.

Amy Coney Barrett was reportedly also on the shortlist to fill the vacancy created by the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy in 2018. Although that seat was eventually filled by now-Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Trump reportedly told advisers that he was “saving” Barrett in case Ginsburg stepped down during his presidency. Barrett became a hero to many religious conservatives after her 2017 confirmation hearing for her seat on the court of appeals, when Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee – most notably, Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California – grilled her on the role of her Catholic faith in judging.

Early life and career

The 48-year-old Barrett grew up in Metairie, Louisiana, a suburb of New Orleans, and attended St. Mary’s Dominican High School, a Catholic girls’ school in New Orleans. Barrett graduated magna cum laude from Rhodes College, a liberal arts college in Tennessee affiliated with the Presbyterian Church, in 1994. (Other high-profile alumni of the school include Abe Fortas, who served as a justice on the Supreme Court from 1965 to 1969, and Claudia Kennedy, the first woman to become a three-star general in the U.S. Army.) At Rhodes, she was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and was also recognized as the most outstanding English major and for having the best senior thesis.

After graduating from Rhodes, Barrett went to law school at Notre Dame on a full-tuition scholarship. She excelled there as well: She graduated summa cum laude in 1997, received awards for having the best exams in 10 of her courses and served as executive editor of the school’s law review.

Barrett then held two high-profile conservative clerkships, first with Judge Laurence Silberman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, from 1997 to 1998, and then with the late Justice Antonin Scalia, from 1998 to 1999. After leaving her Supreme Court clerkship, she spent a year practicing law at Miller, Cassidy, Larroca & Lewin, a prestigious Washington, D.C., litigation boutique that also claims as alumni former U.S. solicitor general Seth Waxman, former deputy attorney general Jamie Gorelick, and John Elwood, the head of Arnold & Porter’s appellate practice and a regular contributor to SCOTUSblog. In 2001, Miller Cassidy merged with Baker Botts, a larger, Texas-based firm, and Barrett spent another year there before leaving for academia. To the chagrin of Democratic senators during her confirmation process for the 7th Circuit, Barrett was able to recall only a few of the cases on which she worked, and she indicated that she never argued any appeals while in private practice.

A prolific stint in academia

Barrett spent a year as a law and economics fellow at George Washington University before heading to her alma mater, Notre Dame, in 2002 to teach federal courts, constitutional law and statutory interpretation. Barrett was named a professor of law at the school in 2010; four years later, she became the Diane and M.O. Research Chair of Law. Barrett was named “distinguished professor of the year” three times.

While at Notre Dame, Barrett signed a 2012 “statement of protest” condemning the accommodation that the Obama administration created for religious employers who were subject to the Affordable Care Act’s birth control mandate. The statement lamented that the accommodation “changes nothing of moral substance and fails to remove the assault on individual liberty and the rights of conscience which gave rise to the controversy.” Barrett was also a member of the Federalist Society, the conservative legal group, from 2005 to 2006 and then again from 2014 to 2017. In response to written questions from Democratic senators during her 7th Circuit confirmation process, Barrett indicated that she had rejoined the group because it gave her “the opportunity to speak to groups of interested, engaged students on topics of mutual interest,” but she added that she had never attended the group’s national convention.

During her 15 years as a full-time law professor, Barrett’s academic scholarship was prolific. Several of her articles, however, drew fire at Barrett’s confirmation hearing, with Democratic senators suggesting that they indicate that Barrett would be influenced by her Catholic faith, particularly on the question of abortion.

Barrett co-wrote her first law review article, “Catholic Judges in Capital Cases,” with Notre Dame law professor John Garvey (now the president of the Catholic University of America); the article was published in the Marquette Law Review in 1998, shortly after her graduation from Notre Dame. It explored the effect of the Catholic Church’s teachings on the death penalty on federal judges, and it used the church’s teachings on abortion and euthanasia as a comparison point, describing the prohibitions on abortion and euthanasia as “absolute” because they “take away innocent life.” The article also noted that, when the late Justice William Brennan was asked about potential conflict between his Catholic faith and his duties as a justice, he responded that he would be governed by “the oath I took to support the Constitution and laws of the United States.” Barrett and Garvey observed that they did not “defend this position as the proper response for a Catholic judge to take with respect to abortion or the death penalty.”

When questioned about the article at her 7th Circuit confirmation hearing, Barrett stressed that she did not believe it was “lawful for a judge to impose personal opinions, from whatever source they derive, upon the law,” and she pledged that her views on abortion “or any other question will have no bearing on the discharge of my duties as a judge.” She acknowledged that, if she were instead being nominated to serve as a federal trial judge, she “would not enter an order of execution,” but she assured senators that she did not intend “as a blanket matter to recuse myself in capital cases if I am confirmed” and added that she had “fully participated in advising Justice Scalia in capital cases as a law clerk.”

Barrett’s responses did not mollify Feinstein, who suggested that Barrett had a “long history of believing that religious beliefs should prevail.” In a widely reported exchange, Feinstein told Barrett that, based on Barrett’s speeches, “the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you. And that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for years in this country.”

In another article, “Stare Decisis and Due Process,” published in the University of Colorado Law Review, Barrett discussed the legal doctrine that generally requires courts to follow existing precedent, even if they might believe that it is wrong. Barrett wrote that courts and commentators “have thought about the kinds of reliance interests that justify keeping an erroneous decision on the books”; in a footnote, she cited (among other things) Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 decision reaffirming Roe v. Wade. Barrett’s detractors characterized the statement as criticism of Roe itself, while supporters such as conservative legal activist Ed Whelan countered that the statement did not reflect Barrett’s views on Roe itself, but instead was just an example of competing opinions on the reliance interests in Roe.

Path to the federal bench

Trump nominated Barrett to the 7th Circuit on May 8, 2017. Despite some criticism from Democrats, she garnered bipartisan support at her confirmation hearing. A group of 450 former students signed a letter to the Senate Judiciary Committee, telling senators that their support was “driven not by politics, but by the belief that Professor Barrett is supremely qualified.” And she had the unanimous support of her 49 Notre Dame colleagues, who wrote that they had a “wide range of political views” but were “united however in our judgment about Amy.”

After Barrett’s confirmation hearing but before the Senate voted on her nomination, The New York Times reported that Barrett was a member of a group called People of Praise. Group members, the Times indicated, “swear a lifelong oath of loyalty to one another, and are assigned and accountable to a personal adviser.” Moreover, the Times added, the group “teaches that husbands are the heads of their wives and should take authority for their family.” The newspaper quoted legal experts who worried that such oaths “could raise legitimate questions about a judicial nominee’s independence and impartiality.”

Barrett declined the Times’ request for an interview about People of Praise, whose website describes the group as an “ecumenical, charismatic, covenant community” modeled on the “first Christian community.” “Freedom of conscience,” the website says, “is a key to our diversity.” In 2018, Slate interviewed the group’s leader, a physics and engineering professor at Notre Dame, who explained that members of the group “often make an effort to live near one another” and agree to donate 5% of their income to the group.

On Oct. 31, 2017, Barrett was confirmed to the 7th Circuit by a vote of 55 to 43. Three Democratic senators – her home state senator, Joe Donnelly; Tim Kaine of Virginia; and Joe Manchin of West Virginia – crossed party lines to vote for her, while two Democratic senators (Claire McCaskill of Missouri and Robert Menendez of New Jersey) did not vote.

Barrett as a judge: Gun rights and abortion

In a story in the National Review in August 2020, conservative legal activist Carrie Severino described Barrett as a “champion of originalism” during her short tenure so far on the 7th Circuit. In the 2019 case Kanter v. Barr, the court of appeals upheld the mail fraud conviction of the owner of an orthopedic footwear company. He argued that federal and state laws that prohibit people convicted of felonies from having guns violate his Second Amendment right to bear arms. The majority rejected that argument. It explained that the government had shown that the laws are related to the government’s important goal of keeping guns away from people convicted of serious crimes.

Barrett dissented. At the time of the country’s founding, she said, legislatures took away the gun rights of people who were believed to be dangerous. But the laws at the heart of Kanter’s case are too broad, she argued, because they ban people like Kanter from having a gun without any evidence that they pose a risk. Barrett stressed that the Second Amendment “confers an individual right, intimately connected with the natural right of self-defense and not limited to civic participation.”

During her time on the court of appeals, Barrett has grappled with the issue of abortion twice – both times in dealing with requests for the full court of appeals to rehear a case, rather than as part of a three-judge panel. In 2018, the full court ordered rehearing en banc in a challenge to an Indiana law requiring fetal remains to be either buried or cremated after an abortion but then vacated that order and reinstated the original opinion blocking the state from enforcing the law.

Barrett joined a dissent from the denial of rehearing en banc written by Judge Frank Easterbrook. Easterbrook began by addressing a separate provision of the law that had also been struck down but was not at issue in the rehearing proceedings: It would bar abortions based on the race, sex or disability (such as Down syndrome) of the fetus. Characterizing the provision as a means of preventing prospective parents from “[u]sing abortion as a way to promote eugenic goals,” Easterbrook expressed doubt that the Constitution bars states from enacting such laws.

Indiana later went to the Supreme Court, which reversed the 7th Circuit’s opinion on the provision governing fetal remains. States have an interest in the proper disposal of fetal remains, the justices reasoned, and this law “is rationally related to” that interest. But the justices did not weigh in on the part of the 7th Circuit’s decision that struck down the ban on abortions based on race, sex or disability, leaving the state unable to enforce that provision.

In 2019, Barrett indicated that she wanted the full 7th Circuit to hear a challenge to an Indiana law requiring young women to notify their parents before obtaining an abortion after a three-judge panel ruled that the law was unconstitutional. She joined a dissent from the denial of rehearing by Judge Michael Kanne, who wrote that “[p]reventing a state statute from taking effect is a judicial act of extraordinary gravity in our federal structure.” The state asked the Supreme Court to weigh in, and the justices sent the case back to the lower courts this summer for another look in light of their ruling in June Medical Services v. Russo, which struck down a Louisiana law that requires doctors who perform abortions to have the right to admit patients at nearby hospitals.

Also in 2019, Barrett joined an opinion that upheld a Chicago ordinance that bars anti-abortion “sidewalk counselors” from approaching women entering an abortion clinic. The Chicago ordinance was modeled after a Colorado law that the Supreme Court upheld in 2000 in Hill v. Colorado, but challengers argued that later decisions by the Supreme Court “have so thoroughly undermined Hill’s reasoning that we need not follow it.” Judge Diane Sykes – who is also on Trump’s list of potential nominees, although now an unlikely candidate at age 62 – wrote that “[t]hat’s a losing argument in the court of appeals. The Court’s intervening decisions have eroded Hill’s foundation, but the case still binds us; only the Supreme Court can say otherwise.” The Supreme Court denied the challengers’ petition for review in July 2020.

Barrett as a judge: Sex discrimination on campus and immigration policy

In Doe v. Purdue University, Barrett wrote for a three-judge panel that reinstated a lawsuit filed against the university and its officials by a student who had been found guilty, through the university’s student discipline program, of sexual violence. One expert who advises colleges and universities on compliance with Title IX, a federal law that bars gender discrimination in education, told The Washington Post that the opinion was a “trendsetter” that would make it easier for students to bring lawsuits against universities to trial.

The student, known as John Doe, was suspended from school, which in turn led to his expulsion from the Navy ROTC program, the loss of his scholarship and the end of his plans to join the Navy after graduation. The court of appeals agreed with the student that he should be allowed to pursue his claim alleging that the process used to determine his guilt or innocence violated the Constitution. “Purdue’s process,” Barrett wrote, “fell short of what even a high school must provide to a student facing a days-long suspension.”

The court also revived the student’s statutory claim under Title IX. Barrett observed that although a 2011 letter from the Department of Education to colleges and universities warning schools to vigorously investigate and punish sexual misconduct or risk losing federal funds would give Doe “a story about why Purdue might have been motivated to discriminate against males accused of sexual assault,” it might not, she observed, standing alone, be enough for his case to go forward. However, she continued, the combination of the letter and facts suggesting that university officials had chosen to believe his alleged victim “because she is a woman and to disbelieve John Doe because he is a man” would suffice for his case to continue.

In June 2020, Barrett dissented from a decision that upheld a district court order blocking the Trump administration from enforcing the “public charge” rule, which bars noncitizens from receiving a green card if the government believes they are likely to rely on public assistance. The district court had put the administration’s 2019 interpretation of the rule on hold, ruling that it likely exceeded the scope of the underlying “public charge” statute, which according to the district court requires a longer and more substantial dependence on government assistance before someone may be considered a “public charge.” In February, a divided Supreme Court issued an emergency order allowing the federal government to begin enforcing the rule while its appeals were pending.

In her dissent, Barrett rejected the challengers’ efforts to portray the public charge statute as narrow. The current law, she explained, “was amended in 1996 to increase the bite of the public charge determination.” As a result, she continued, it is “not unreasonable to describe someone who relies on the government to satisfy a basic necessity for a year, or multiple basic necessities for a period of months, as falling within the definition of a term that denotes a lack of self-sufficiency.” What the challengers are really objecting to, she suggested, is “this policy choice” or even the very idea of excluding legal immigrants who are deemed likely to depend on government assistance. But, she concluded, litigation “is not the vehicle for resolving policy disputes.”

In Yafai v. Pompeo, Barrett wrote for a three-judge panel that agreed that the wife of a U.S. citizen could not challenge the denial of her visa application. A consular officer rejected the application by Zahoor Ahmed, a Yemeni citizen, on the ground that she had attempted to smuggle two children into the United States. Ahmed and her husband told the embassy that the children she was accused of smuggling had died in a drowning accident and provided documentation, at the embassy’s request.

Relying on a doctrine known as consular nonreviewability, which prohibits courts from reviewing visa decisions made by consular officials overseas, Barrett concluded that it was enough that the consular officer cited the provision of federal immigration law on which he relied and the basic facts at the heart of her case. Because Ahmed and her husband did not show that the consular officer had acted in bad faith in denying her visa application, courts could not look behind that decision. If anything, Barrett suggested, the fact that consular officers had asked for additional documents “suggests a desire to get it right,” and she said that an email from an embassy officer to Ahmed’s lawyer “reveals good-faith reasons for rejecting the plaintiffs’ response to the smuggling charge.”

Barrett as a judge: Other cases

One case that would almost certainly draw attention if she were nominated came shortly after she took the bench: EEOC v. AutoZone, in which the federal government asked the full court of appeals to reconsider a ruling against the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in its lawsuit against AutoZone, an auto parts store. The EEOC had argued that the store violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which bars employees from segregating or classifying employees based on race, when it used race as a determining factor in assigning employees to different stores – for example, sending African American employees to stores in heavily African American neighborhoods. A three-judge panel (that did not include Barrett) ruled for AutoZone; Barrett joined four of her colleagues in voting to deny rehearing by the full court of appeals.

Three judges – Chief Judge Diane Wood and Judges Ilana Diamond Rovner and David Hamilton – would have granted rehearing en banc. Those three also had strong words in the dissenting opinion they filed. They alleged that, under “the panel’s reasoning, this separate-but-equal arrangement is permissible under Title VII as long as the ‘separate’ facilities really are ‘equal’” – a conclusion, they continued, that is “contrary to the position that the Supreme Court has taken in analogous equal protection cases as far back as Brown v. Board of Education.”

In Schmidt v. Foster, Barrett dissented from the panel’s ruling in favor of a Wisconsin man who admitted that he had shot his wife seven times, killing her in their driveway. Scott Schmidt argued that he had been provoked, which would make his crime second-degree, rather than first-degree, homicide. The trial judge in a state court reviewed that claim at a pretrial hearing that prosecutors did not attend, and at which Schmidt’s attorney was not allowed to speak. The judge rejected Schmidt’s claim of provocation, and Schmidt was convicted of first-degree homicide and sentenced to life in prison. When Schmidt sought to overturn his conviction in federal court, the panel agreed that Schmidt had been denied his Sixth Amendment right to counsel, and the court of appeals sent the case back to the lower court.

Barrett disagreed with her colleagues. Her dissent began by emphasizing that the standard for federal post-conviction relief is “intentionally difficult because federal habeas review of state convictions” interferes with the states’ efforts to enforce their own laws. In this case, she contended, the state court’s decision rejecting Schmidt’s Sixth Amendment claim could not have been “contrary to” or “an unreasonable application of” clearly established federal law (the requirement for relief in federal court) because the Supreme Court has never addressed a claim that a defendant has a right to counsel in a pretrial hearing like the one at issue in this case. While acknowledging that “[p]erhaps the right to counsel should extend to a hearing like the one the judge conducted in Schmidt’s case,” she warned that federal law “precludes us from disturbing a state court’s judgment on the ground that a state court decided an open question differently than we would — or, for that matter, differently than we think the [Supreme] Court would.”

In Akin v. Berryhill, Barrett joined an unsigned decision in favor of a woman whose application for Social Security disability benefits had been denied by an administrative law judge. The panel agreed with the woman, Rebecca Akin, that the judge had incorrectly “played doctor” by interpreting her MRI results on his own, and it instructed the judge to take another look at his determination that Akin was not credible. The panel indicated that it was “troubled by the ALJ’s purported use of objective medical evidence to discredit Akin’s complaints of disabling pain,” noting that fibromyalgia (one of Akin’s ailments) “cannot be evaluated or ruled out by using objective tests.” It added that, among other things, the administrative law judge should not have discredited Akin’s choice to go with a more conservative course of treatment when she explained that “she was afraid of needles and that she wanted to wait until her children finished school before trying more invasive treatment.”

Barrett has been married for over 18 years to Jesse Barrett, a partner in a South Bend law firm who spent 13 years as a federal prosecutor in Indiana. They have seven children (only two fewer than her old boss, Scalia). At her 7th Circuit confirmation hearing, Barrett introduced three of her daughters, who were sitting behind her. She told senators that one daughter, then-13-year-old Vivian, was adopted from Haiti at the age of 14 months, weighing just 11 pounds; she was so weak at the time that the Barretts were told she might never walk normally or talk. The Barretts adopted a second child, Jon Peter, from Haiti after the 2011 earthquake, and Barrett described their youngest child, Benjamin, as having special needs that “present unique challenges for all of us.” Since becoming a judge, Barrett has reportedly commuted from her home in South Bend to Chicago, roughly 100 miles away, a few days a week. If she were nominated and confirmed to fill Ginsburg’s seat, she would likely move her family to the Washington, D.C., area and trade that commute for a shorter one to 1 First Street, N.E.

Source: Scotusblog.com