The legally binding agreement is structured in such a way that it sidesteps U.S. Senate approval for the United States to join, which is required for treaties.

As the May deadline approaches for finalizing negotiations between the World Health Organization (WHO) and its 194 member nations over how much authority they will cede to the WHO once it declares a global health emergency, many health and policy experts are urging the Biden administration not to sign the United States up to the agreement.

In February 2023, WHO member states negotiated the “Zero Draft” of a new treaty, which wasn’t identified as a treaty but rather as the “WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response (WHO CA+).”

This WHO CA+, which functions as a treaty, has gone through an opaque process of negotiation and amendments ever since, from which the public has been essentially excluded, with the goal of signing it this year.

Among the goals for the United States, as set by the Biden administration, are to “strengthen the global health security architecture, including WHO strengthening, and engage in ongoing negotiations to amend the IHR and develop a Pandemic Accord.”

A Dec. 30, 2023, White House fact sheet states, “Global health security is vital for international security and solidarity, and cannot be achieved alone.”

When a Treaty Isn’t a Treaty

Reggie Littlejohn, president of Women’s Rights Without Frontiers, criticized the WHO draft document for being crafted in a way that the Biden administration can sign the United States up to it without Senate approval.

“The WHO refuses to call the pandemic treaty a treaty,” she said at a press conference organized by Rep. Chris Smith (R-N.J.), chairman of the Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Subcommittee.

“It calls it an agreement, an accord, a framework—anything else. Likely because it does not want it to be submitted to the treaty process in the United States and worldwide,” Ms. Littlejohn said.

According to the WHO, the agreement, once signed by members, will be legally binding.

“Conventions, framework agreements, and treaties are all examples of international instruments, which are legal agreements made between countries that are binding,” the WHO states.

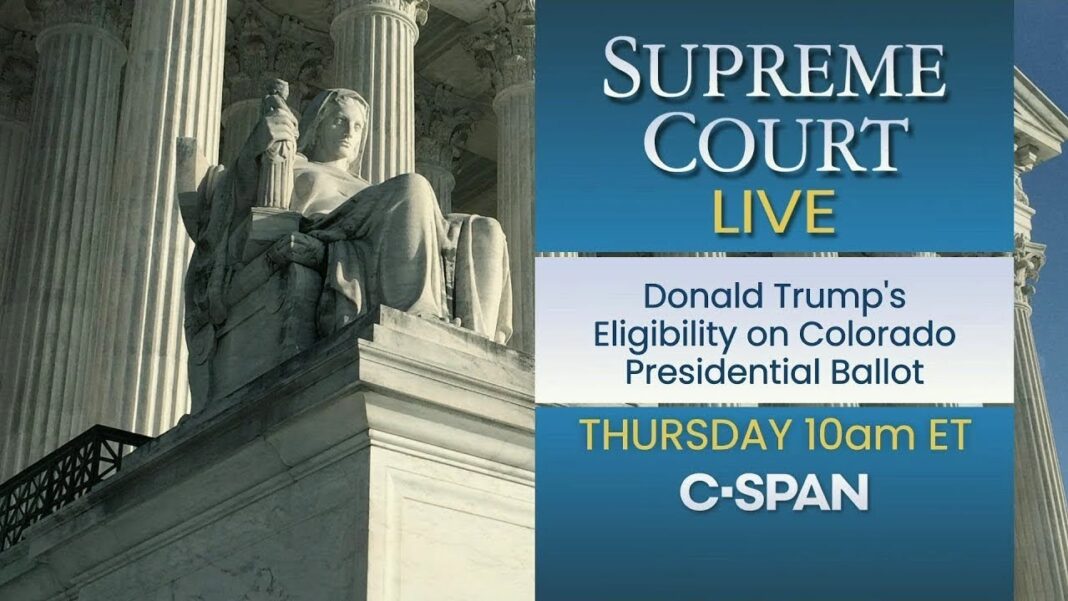

The U.S. Constitution gives the president the authority to enter into treaties, which are agreements between the United States and foreign entities, “provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.”

Given the opposition to the WHO treaty, particularly from Republicans, it seems unlikely it would pass the Senate.