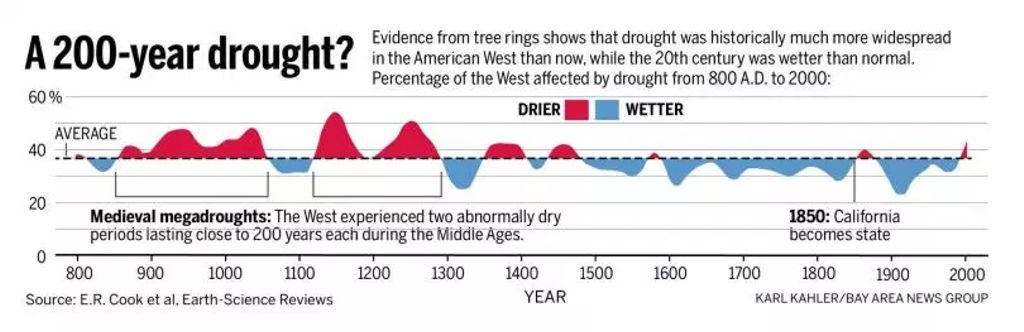

The Mercury News ~ California’s current drought is being billed as the driest period in the state’s recorded rainfall history. But scientists who study the West’s long-term climate patterns say the state has been parched for much longer stretches before that 163-year historical period began.

And they worry that the “megadroughts” typical of California’s earlier history could come again.

Through studies of tree rings, sediment and other natural evidence, researchers have documented multiple droughts in California that lasted 10 or 20 years in a row during the past 1,000 years — compared to the mere three-year duration of the current dry spell. The two most severe megadroughts make the Dust Bowl of the 1930s look tame: a 240-year-long drought that started in 850 and, 50 years after the conclusion of that one, another that stretched at least 180 years.

“We continue to run California as if the longest drought we are ever going to encounter is about seven years,” said Scott Stine, a professor of geography and environmental studies at Cal State East Bay. “We’re living in a dream world.”

California in 2013 received less rain than in any year since it became a state in 1850. And at least one Bay Area scientist says that based on tree ring data, the current rainfall season is on pace to be the driest since 1580 — more than 150 years before George Washington was born. The question is: How much longer will it last?

A megadrought today would have catastrophic effects.

California, the nation’s most populous state with 38 million residents, has built a massive economy, Silicon Valley, Hollywood and millions of acres of farmland, all in a semiarid area. The state’s dams, canals and reservoirs have never been tested by the kind of prolonged drought that experts say will almost certainly occur again.

Stine, who has spent decades studying tree stumps in Mono Lake, Tenaya Lake, the Walker River and other parts of the Sierra Nevada, said that the past century has been among the wettest of the last 7,000 years.

Looking back, the long-term record also shows some staggeringly wet periods. The decades between the two medieval megadroughts, for example, delivered years of above-normal rainfall — the kind that would cause devastating floods today.

The longest droughts of the 20th century, what Californians think of as severe, occurred from 1987 to 1992 and from 1928 to 1934. Both, Stine said, are minor compared to the ancient droughts of 850 to 1090 and 1140 to 1320.

Modern megadrought

What would happen if the current drought continued for another 10 years or more?

Without question, longtime water experts say, farmers would bear the brunt. Cities would suffer but adapt.

The reason: Although many Californians think that population growth is the main driver of water demand statewide, it actually is agriculture. In an average year, farmers use 80 percent of the water consumed by people and businesses — 34 million of 43 million acre-feet diverted from rivers, lakes and groundwater, according to the state Department of Water Resources.

“Cities would be inconvenienced greatly and suffer some. Smaller cities would get it worse, but farmers would take the biggest hit,” said Maurice Roos, the department’s chief hydrologist. “Cities can always afford to spend a lot of money to buy what water is left.”

Roos, who has worked at the department since 1957, said the prospect of megadroughts is another reason to build more storage — both underground and in reservoirs — to catch rain in wet years.

In a megadrought, there would be much less water in the Delta to pump. Farmers’ allotments would shrink to nothing. Large reservoirs like Shasta, Oroville and San Luis would eventually go dry after five or more years of little or no rain.

Farmers would fallow millions of acres, letting row crops die first. They’d pump massive amounts of groundwater to keep orchards alive, but eventually those wells would go dry. And although deeper wells could be dug, the costs could exceed the value of their crops. Banks would refuse to loan the farmers money.

The federal government would almost certainly provide billions of dollars in emergency aid to farm communities.

“Some small towns in the Central Valley would really suffer. They would basically go away,” said Jay Lund, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis.

“But agriculture is only 3 percent of California’s economy today,” Lund said. “In the main urban economy, most people would learn to live with less water. It would be expensive and inconvenient, but we’d do it.”

Farmers with senior water rights would make a huge profit, he noted, selling water at sky-high prices to cities. Food costs would rise, but there wouldn’t be shortages, Lund said, because Californians already buy lots of food from other states and countries and would buy even more from them.

Fallback plans

In urban areas, most cities would eventually see water rationing at 50 percent of current levels. Golf courses would shut down. Cities would pass laws banning watering or installing lawns, which use half of most homes’ water. Across the state, rivers and streams would dry up, wiping out salmon runs. Cities would race to build new water supply projects, similar to the $50 million wastewater recycling plant that the Santa Clara Valley Water District is now constructing in Alviso.

If a drought lasted decades, the state could always build dozens of desalination plants, which would cost billions of dollars, said law professor Barton “Buzz” Thompson, co-director of Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment.

Saudi Arabia, Israel and other Middle Eastern countries depend on desalination, but water from desal plants costs roughly five times more than urban Californians pay for water now. Thompson said that makes desal projects unfeasible for most of the state now, especially when other options like recycled wastewater and conservation can provide more water at a much lower cost.

But in an emergency, price becomes no object.

“In theory, cities cannot run out of water,” Thompson said. “All we can do is run out of cheap water, or not have as much water as we need when we really want it.”

Over the past 10 years, he noted, Australia has been coping with a severe drought. Urban residents there cut their water demand massively, built new supply projects and survived.

“I don’t think we’ll ever get to a point here where you turn on the tap and air comes out,” he said.

Megadrought now

Some scientists believe we are already in a megadrought, although that view is not universally accepted.

Bill Patzert, a research scientist and oceanographer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, says that the West is in a 20-year drought that began in 2000. He cites the fact that a phenomenon known as a “negative Pacific decadal oscillation” is underway — and that historically has been linked to extreme high-pressure ridges that block storms.

Such events, which cause pools of warm water in the North Pacific Ocean and cool water along the California coast, are not the result of global warming, Patzert said. But climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels has been linked to longer heat waves. That wild card wasn’t around years ago.

“Long before the Industrial Revolution, we were vulnerable to long extended periods of drought. And now we have another experiment with all this CO2 in the atmosphere where there are potentially even more wild swings in there,” said Graham Kent, a University of Nevada geophysicist who has studied submerged ancient trees in Fallen Leaf Lake near Lake Tahoe.

Already, the 2013-14 rainfall season is shaping up to be the driest in 434 years, based on tree ring data, according to Lynn Ingram, a paleoclimatologist at UC Berkeley.

“It’s important to be aware of what the climate is capable of,” she said, “so that we can prepare for it.”

By Paul Rogers who covers resources and environmental issues. Contact him at 408-920-5045. Follow him at Twitter.com/PaulRogersSJMN.