There was a time (up until the late 19th century) when Africans owned cattle and land of their own choosing in South Africa – it was their right. Then came the advent of European settlers and by the 1950s, it was all taken away from them with no compensation under the Group Areas Act. This legislation held that South Africa’s apartheid government could choose certain areas to be used by a single race.

Time has a way of changing things, though. In the early 1990s, South Africa’s new constitution allowed for land (previously taken from black farmers under apartheid) to be returned to them. What is often overlooked (purposely or otherwise) is that the constitution was conceived with care and due diligence – not punitive intent.

For some, however, progress on land reform has been too slow – too little too late. In January, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed into law a measure (Expropriation Act 13 of 2024) that allows, in some circumstances, land to be seized by the state without compensation.

Opponents argue it is a threat to the principle of private ownership. And among those opponents is Donald Trump. He has said the new bill constituted “hateful rhetoric” towards “racially disfavored landowners.”

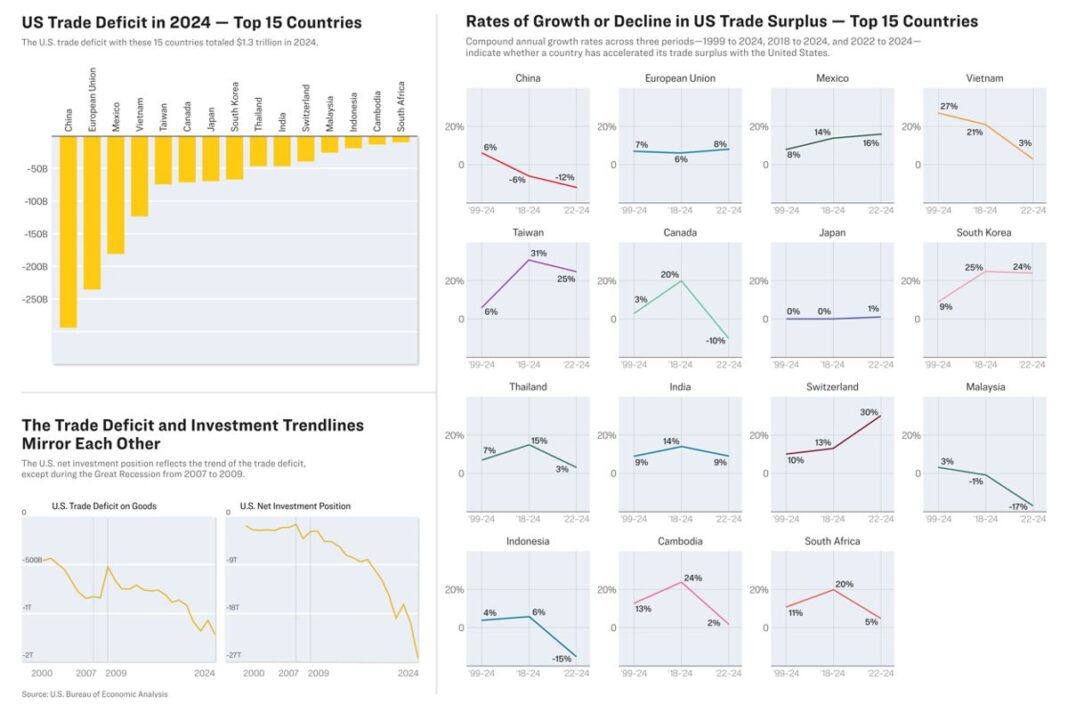

Moreover, Mr. Trump announced he would pause all aid to South Africa, valued at roughly $320 million (£253 million) according to the US Agency for International Development. Some worry he might eventually exclude South Africa from a trade agreement, estimated by the Office of the US Trade Representative to be worth $14.7 billion (£11.6 billion) a year.

The challenge facing Ramaphosa is daunting, indeed. Can he implement land reform in a way to appease friend and foe alike, without sacrificing the US as a critical trading partner?

Property rights and compensation

There are, of course, a large contingent of Afrikaner farmers, descendants of Huguenots who once fled France. Many work and live on farms as descendants of families having previously “acquired” the land. They grow a variety of crops: maize, soybeans, etc., as well as graze sheep and cattle. In some cases, farms are spread across hundreds or even thousands of hectares.

Many Afrikaner farmers were born on these farms and have worked them for decades; they contend that the new expropriation act threatens property rights and is a source of great concern for them.

Yet, expropriation need not be a problem if there’s compensation, but the compensation must be just, fair and equitable. Moreover, without private property rights, farmers will not be able to borrow money and finance their crops.

Farmers say it becomes an economic issue for South Africa, itself: it is not economically viable to invest in the country if property rights are not protected.

In agriculture, private property is critical to accessing capital; farmers need to finance their purchases via banks or from agricultural corporations to cover operating costs. If property rights are not available, access to capital is limited.

The impact the law could have on foreign investment is, of course, of concern to AfriForum, a group that seeks to protect the rights of Afrikaners. AfriForum CEO Kallie Kriel asserts that international investors, if they hear the phrase “no compensation,” will defer investment in South Africa.

On the other hand, the constitution and new expropriation act are genuine efforts to redress generations of inequity. Land reform in South Africa, contrary to some views, is not necessarily a governmental “land grab.” What the president is proposing is a constitutionally-managed process of land reform for the public good – the European Afrikaner and native people of South Africa must share in the land.

Structural apartheid

Professor Ruth Hall of the University of the Western Cape argues: the issue of access to land in South Africa dates back to before the start of formal apartheid in 1948.

In fact, by the end of the 19th Century, most of the land that is currently South Africa had been taken over by Europeans.

The Natives’ Land Act of 1913 defined less than one-tenth of South Africa as “Black reserves” and prohibited any purchase or lease of land by the native population outside these areas.

The subsequent Group Areas Act only reinforced the division and further reduced economic opportunities for black people.

Too much land in too few hands

Agriculture remains one of the main sources of economic revenue for the country. Unfortunately, the majority of commercial agricultural land remains in the hands of the predominately European Afrikaner minority which constitutes roughly 7.3% of the population.

A critical issue is whether the “no-compensation clause” in the law breaches section 25 of the South African Constitution, which establishes property rights for all South Africans.

The time for change is overdue

In 1996, the South African government launched its land reform program. It promised to settle all claims for redistribution by 2005 and redistribute 30% of Afrikaner-owned commercial agricultural land to black South Africans by 2014.

The fact that neither target was met helps explain the pressure for the more restrictive legislation.

To be clear, no large-scale land seizures have taken place, and the majority of land still remains in the hands of the predominately European Afrikaner minority.

The US president responds

As of this writing, the debate around land ownership has transcended the borders of South Africa with the recent intervention of US President Donald Trump. The president issued an executive decision on the land issue in early February just a few weeks after taking the oath of office. The order claimed the expropriation act would “enable the government of South Africa to seize ethnic minority Afrikaners’ agricultural property without compensation.”

The executive order further claimed that the act was part of a number of discriminatory policies and “hateful rhetoric” directed towards “racially disfavored landowners.”

The American president also accused Pretoria of taking aggressive positions towards the United States and its allies; he stated that the South African government is strengthening its relations with Iran and has falsely accused Israel (at the International Court of Justice (ICJ)) of genocide in Gaza..

As a result of these actions, Trump said he would pause all aid to South Africa and offered to resettle all “Afrikaner refugees escaping government-sponsored race-based discrimination.”

To date, there have been almost 70,000 South Africans seeking (from the US Embassy in Pretoria) more information about refugee status.

Pretoria’s case against Israel is seen by some as evidence that it supports Hamas and seeks closer ties with Iran.

South Africa is attempting to sustain a relationship with the US and Europe, while also trying to build on its relationship with its partners in the Global South – a monumental task.

Every year, the US president reviews which African countries should continue to be part of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). It allows some African countries to export goods to the US duty free and is credited with creating thousands of jobs across the continent, including in South Africa.

There are fears that Donald Trump’s promise to cut all “future funding to South Africa” may see South Africa excluded from AGOA.

Is what is necessary possible?

Can the South African government, and President Cyril Ramaphosa specifically, satisfy those who believe further land reform is a must without being frozen out economically by the US and losing foreign investors?

After Mr. Trump’s funding freeze, Mr. Ramaphosa said South Africa will not be bullied. It’s one of the few positions with which all his coalition partners seem to agree. There appears to be little indication that the South African government will reverse its position on the new law.

The Expropriation Act was passed by a democratic parliament and signed into law by the South African president – it seems inevitable now that Ramaphosa feels obligated to implement the statute.

South Africa is already feeling the effects of US diplomatic pressure: both the US secretary of state and the treasury secretary have refused to join their counterparts at the recent G20 meetings hosted by South Africa.

Moreover, South Africa’s Ambassador to the US, Ebrahim Rasool, has recently been declared “persona non grata” in the US and has been ordered to leave the country forthwith. US Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, took issue with remarks made by the ambassador allegedly directed at both President Trump and Starlink CEO Elon Musk — who has his own issues with South Africa.

President Ramaphosa has promised to send envoys to the US and other countries to explain South Africa’s position on the expropriation act, the war in the Middle East, as well as some of its other foreign policy initiatives (e g. BRICS+).

Whether South Africa can quell the current hostility emanating from Washington, without compromising on its national priorities, is a formidable test for a country essentially trying to fulfill its obligations as a true democracy.