Each year, The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength employs a standardized, consistent set of criteria, accessible both to government officials and to the American public, to gauge the U.S. military’s ability to perform its missions in today’s world.

2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength

“As currently postured, the U.S. military is at growing risk of not being able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests. It is rated as weak relative to the force needed to defend national interests on a global stage against actual challenges in the world as it is rather than as we wish it were. This is the logical consequence of years of sustained use, underfunding, poorly defined priorities, wildly shifting security policies, exceedingly poor discipline in program execution, and a profound lack of seriousness across the national security establishment even as threats to U.S. interests have surged.”

The United States maintains a military force to protect the homeland from attack and to protect its interests abroad. There are other uses, of course—for example, to assist civil authorities in times of emergency or to deter enemies—but this force’s primary purpose historically has been to make it possible for the U.S. to physically impose its will on an enemy when necessary.

It is therefore critical that the American people understand the condition of the United States military with respect to America’s vital national security interests, threats to those interests, and the context within which the U.S. might have to use “hard power” to protect those interests. Because changes can have substantial implications for defense policies and investment, knowing how these three areas change over time is likewise important. Of the three, the condition of the military is the most important to understand because it is the only one over which the U.S. has complete control, and it underwrites the ability of all other aspects of national power to flourish or fail.

Each year, The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength employs a standardized, consistent set of criteria, accessible both to government officials and to the American public, to gauge the U.S. military’s ability to perform its missions in today’s world. The inaugural 2015 edition established a baseline assessment on which each annual edition builds, one that both assesses the state of affairs for its respective year and measures how key factors have changed during the preceding year.

The Index is not an assessment of what might be, although the trends that it captures may well imply both concerns and opportunities that can guide decisions that are germane to America’s security. Rather, the Index should be seen as a report card for how well or poorly conditions, countries, and the U.S. military have evolved during the assessed year. The past cannot be changed, but it can inform, just as the future cannot be predicted but can be shaped.

2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength

What the Index Assesses

The Index of U.S. Military Strength assesses the ease or difficulty of operating in key regions based on existing alliances, regional political stability, the presence of U.S. military forces, and the condition of key infrastructure. Threats are assessed based on the behavior and physical capabilities of actors that pose challenges to vital U.S. national interests. The condition of America’s military power is measured in terms of its capability or modernity, capacity for operations, and readiness to handle assigned missions. This framework provides a single-source reference for policymakers and other Americans who seek to know whether our military is up to the task of defending our national interests.

Any discussion of the aggregate capacity and breadth of the military power needed to protect U.S. security interests requires a clear understanding of precisely what interests must be defended. Three vital interests have been specified consistently (albeit in varying language) by a string of Administrations over the past few decades:

- Defense of the homeland;

- Successful conclusion of a major war that has the potential to destabilize a region of critical interest to the U.S.; and

- Preservation of freedom of movement within the global commons (the sea, air, outer space, and cyberspace domains) through which the world conducts its business.

To defend these interests effectively on a global scale, the United States needs a military force of sufficient size: what is known in the Pentagon as capacity. The many factors involved make determining how big the military should be a complex exercise, but successive Administrations, Congresses, Department of Defense staffs, and independent commissions have managed to arrive at a surprisingly consistent force-sizing rationale: an ability to handle two major conflicts simultaneously or in closely overlapping time frames.

At its root, the current National Defense Strategy (NDS) implies the same force requirement.1 undefinedundefined Its emphasis on a return to long-term competition with major powers, explicitly naming Russia and China as primary competitors,2 undefined reemphasizes the need for the United States to have:

- Sufficient military capacity to deter or win against large conventional powers in geographically distant regions,

- The ability to conduct sustained operations against lesser threats, and

- The ability to work with allies and maintain a U.S. presence in regions of key importance that is sufficient to deter behavior that threatens U.S. interests.

No matter how much America desires that the world be a simpler, less threatening place that is more inclined to beneficial economic interactions than violence-laden friction, the patterns of history show that competing powers consistently emerge and that the U.S. must be able to defend its interests in more than one region at a time. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s dramatic expansion of its military and its provocative behavior far beyond the Indo-Pacific region, North Korea’s intransigence with respect to even discussing its nuclear capabilities, and Iran’s dogged pursuit of a nuclear weapon capability and sustained support for terrorist groups illustrate this point. Consequently, this Index embraces the two-war or two-contingency requirement.

Since its founding, the U.S. has been involved in a major “hot” war every 15–20 years. Since World War II, the U.S. has also maintained substantial combat forces in Europe and other regions while simultaneously fighting major wars as circumstances demanded. The size of the total force roughly approximated the two-contingency model, which has the inherent ability to meet multiple security obligations to which the U.S. has committed itself while also modernizing, training, educating, and maintaining the force. Accordingly, our assessment of the adequacy of today’s U.S. military is based on the ability of America’s armed forces to engage and defeat two major competitors at roughly the same time.

We acknowledge that without a dramatic change in circumstances such as the onset of a major conflict, a multitude of competing interests that evolve during extended periods of peace and prosperity will cause Administrations and Congresses to favor spending on domestic programs rather than investing in defense. Extended peace leads to complacency, which can lead to distraction and less willingness to invest in defense. The result: a weakened military, competitors that are emboldened, and a nation at risk. Consequently, winning the support needed to increase defense spending to the level that a force with a two-war capacity requires is admittedly difficult politically. But this does not change the patterns of history, the behavior of competitors, or the reality of what it takes to defend America’s interests in an actual war.

This Index’s benchmark for a two-war force is derived from a review of the forces used for each major war that the U.S. has undertaken since World War II and the major defense studies completed by the federal government over the past 30 years. We concluded that a standing (Active Component) two-war–capable force would consist of:

- Army: 50 brigade combat teams (BCTs);

- Navy: 400 battle force ships and 624 strike aircraft;

- Air Force: 1,200 fighter/ground-attack aircraft;

- Marine Corps: 30 battalions; and

- Space Force: metric not yet established.

This recommended force does not account for homeland defense missions that would accompany a period of major conflict and are generally handled by Reserve and National Guard forces. Nor does it constitute the totality of the Joint Force, which includes the array of supporting and combat-enabling functions that are essential to the conduct of any military operation: logistics; transportation (land, sea, and air); health services; communications and data handling; and force generation (recruiting, training, and education) to name only a few. Rather, these are combat forces that are the most recognizable elements of America’s hard power but that also can be viewed as surrogate measures for the size and capability of the larger Joint Force.

2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength

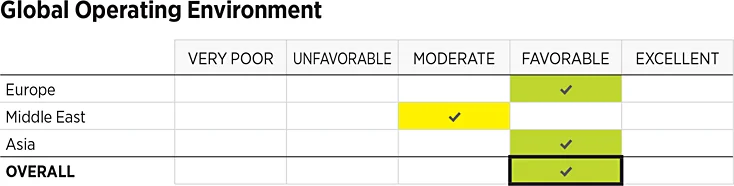

The Global Operating Environment

The United States is a global power with global security interests, and its military must be able to protect those interests anywhere they are threatened. While this may occur in any region, three regions—Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—stand apart because of the scale and scope of U.S. interests associated with them and the significance of competitors that are able to pose commensurately large threats. Aggregating the three regional scores provides a global operating environment score of FAVORABLE in the 2023 Index.

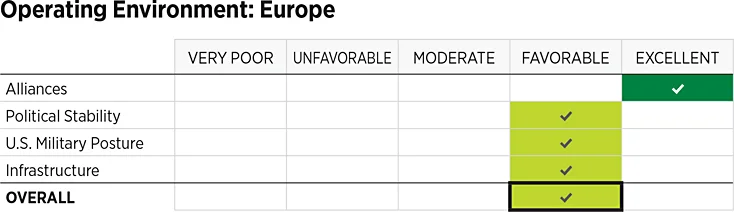

Europe. Overall, the European region remains stable, mature, and friendly to U.S. military operational requirements. Russia remains the preeminent military threat to the region, both conventionally and unconventionally, and its invasion of Ukraine marks a serious escalation in its efforts to exert influence on its periphery. China continues to have a significant presence in Europe and, by mitigating sanctions, has been a key enabler of the Russian government’s ability to conduct the war in Ukraine.

The past year saw continued U.S. reengagement with the continent along with increases in European allies’ defense budgets and capability investment spurred by alarm over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and related threats to countries that are supporting Ukraine’s defense.

It is difficult to predict whether NATO’s renewed emphasis on collective defense and its reinvigorated defense spending will continue in the long term or whether this is a short-term response to Russia’s invasion. We hope for the former but must plan against the latter.

For Europe, scores this year remained steady, as they did in 2021 (assessed in the 2022 Index), with no substantial changes in any individual categories or average scores. The 2023 Index again assesses the European operating environment as “favorable.”

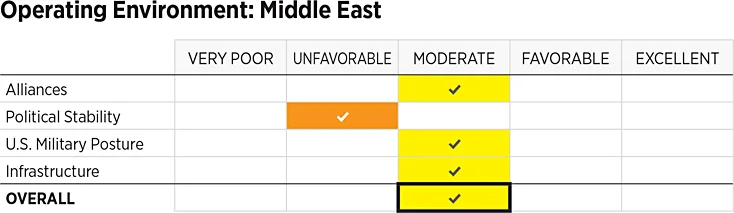

The Middle East. The Middle East region is now highly unstable, both because its authoritarian regimes have eroded and because it continues to serve as a breeding ground for terrorism. Overall, regional security has continued to deteriorate. Although Iraq has restored its territorial integrity since the defeat of ISIS, the political situation and future relations between Baghdad and the United States will remain difficult as long as a government that is sympathetic to Iran is in power. U.S. relations in the region will remain complex, but this has not stopped the U.S. military from operating as needed.

The region’s primary challenges—continued meddling by Iran and surging transnational terrorism—are made more difficult by Sunni–Shia sectarian divides, the more aggressive nature of Iran’s Islamist revolutionary nationalism and its open pursuit of nuclear weapon capabilities, and the proliferation of Sunni Islamist revolutionary groups.

In the Middle East, the U.S. benefits from operationally proven procedures that leverage bases, infrastructure, and the logistical processes needed to maintain a large force forward deployed thousands of miles away from the homeland. The personal links between allied armed forces are also present, and joint training exercises improve interoperability and give the U.S. an opportunity to influence some of the region’s future leaders.

America’s relationships in the region are pragmatic, based on shared security and economic concerns. As long as these issues remain relevant to both sides, the U.S. is likely to have an open door to operate in the Middle East when its national interests require that it do so.

Although circumstances in all measured areas vary throughout the year, in general terms, the 2023 Index assesses the Middle East operating environment as “moderate,” but the region’s political stability continues to be “unfavorable” and will remain a dark cloud over everything else.

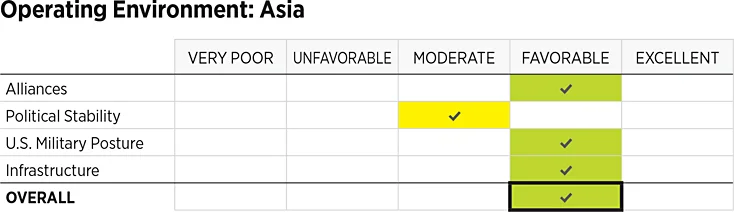

Asia. The Asian strategic environment includes half of the globe and is characterized by a variety of political relationships among states with wildly varying capabilities. This makes Asia far different from Europe, which in turn makes America’s relations with the region different from its relations with Europe. American conceptions of Asia must recognize the physical limitations imposed by the tyranny of distance and the need to move forces as necessary to respond to challenges from China and North Korea.

The complicated nature of intra-Asian relations and the lack of an integrated, regional security architecture along the lines of NATO make defense of U.S. security interests more challenging than many Americans appreciate. However, the U.S. has strong relations with allies in the region, and their willingness to host bases helps to offset the vast distances that must be covered.

The militaries of Japan and the Republic of Korea are larger and more capable than European militaries, and both countries are becoming more interested in developing missile defense capabilities that will be essential in combatting the regional threat posed by North Korea. In Japan, the growing public awareness of the need to adopt a more “normal” posture militarily in response to China’s increasingly aggressive actions indicates a break with the pacifist tradition among the Japanese since the end of World War II. This could lead to improved military capabilities and the prospect of joining the U.S. in defense measures beyond the immediate vicinity of Japan.

We continue to assess the Asia region as “favorable” to U.S. interests in terms of alliances, overall political stability, militarily relevant infrastructure, and the presence of U.S. military forces.

Summarizing the condition of each region enables us to get a sense of how they compare in terms of the difficulty that would be involved in projecting U.S. military power and sustaining combat operations in each one. As a whole, the global operating environment maintains a score of “favorable,” which means that the United States should be able to project military power anywhere in the world to defend its interests without substantial opposition or high levels of risk other than those imposed by a capable enemy.

2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength

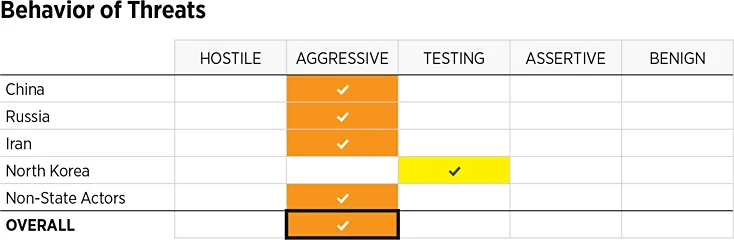

Threats to U.S. Interests

America faces challenges to its security at home and interests abroad from countries and organizations that have:

- Interests that conflict with those of the United States;

- Sometimes hostile intentions toward the U.S.; and

- In some cases, growing military capabilities that are leveraged to impose an adversary’s will by coercion or intimidation of neighboring countries, thereby creating regional instabilities.

The government of the United States constantly faces the challenge of employing the right mix of diplomatic, economic, public information, intelligence, and military capabilities to protect and advance its interests. Because this Index focuses on the military component of national power, its assessment of threats is correspondingly an assessment of the military or physical threat posed by each entity addressed in this section.

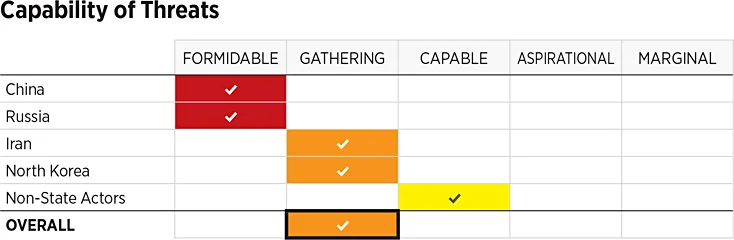

Russia remains the primary threat to American interests in Europe as well as the most pressing threat to the United States. Its invasion of Ukraine reintroduced conventional war to Europe. It also is the largest conflict on that continent since the end of the Second World War, and its many economic and security repercussions are felt across the globe. Moscow also remains committed to massive pro-Russia propaganda campaigns in other Eastern European countries as well as disruptive activities around its periphery and across the Middle East.

The 2023 Index again assesses the threat emanating from Russia as “aggressive” in its behavior and “formidable” (the highest category on the scale) in its growing capabilities. Though Russia is consuming its inventory of munitions, supplies, equipment, and even military personnel in its war against Ukraine, it is also replacing those items and people. Unlike Ukraine’s, Russia’s industrial capacity remains untouched by the war, and will allow Moscow to replace older equipment lost in the conflict with newly manufactured items. Russia’s military is also gaining valuable combat experience. Consequently, the war may actually serve to increase the challenge that Russia poses to U.S. interests on the continent.

China, the most comprehensive threat the U.S. faces, remained “aggressive” in the scope of its provocative behavior and earns the score of “formidable” for its capability because of its continued investment in the modernization and expansion of its military and the particular attention it has paid to its space, cyber, and artificial intelligence capabilities. The People’s Liberation Army continues to extend its reach and military activity beyond its immediate region and engages in larger and more comprehensive exercises, including live-fire exercises in the East China Sea near Taiwan and aggressive naval and air patrols in the South China Sea.

China also continues to conduct probes of the South Korean and Japanese air defense identification zones, drawing rebukes from both Seoul and Tokyo, and its statements about Taiwan and exercise of military capabilities in the air and sea around the island have been increasingly belligerent. China is taking note of the war in Ukraine and U.S. military developments and has been adjusting its own posture, training, and investments accordingly.

Iran represents by far the most significant security challenge to the United States, its allies, and its interests in the greater Middle East. Its open hostility to the United States and Israel, sponsorship of terrorist groups like Hezbollah, and history of threatening the commons underscore the problem it could pose. Today, Iran’s provocations are of primary concern to the region and America’s allies, friends, and assets there. Iran relies heavily on irregular (to include political) warfare against others in the region and fields more ballistic missiles than any of its neighbors.

Iran’s development of ballistic missiles and its potential nuclear capability also make it a long-term threat to the security of the U.S. homeland. In addition, Iran has continued its aggressive efforts to shape the domestic political landscape in Iraq, adding to the region’s general instability. The 2023 Index extends the 2022 Index’s assessment of Iran’s behavior as “aggressive” and its capability as “gathering.”

North Korea’s military poses a security challenge for American allies South Korea and Japan, as well as for U.S. bases in those countries and on the island territory of Guam. North Korean officials are belligerent toward the United States, often issuing military and diplomatic threats. Pyongyang also has engaged in a range of provocative behavior that includes nuclear and missile tests and tactical-level attacks on South Korea. It has used its missile and nuclear tests to enhance its prestige and importance domestically, regionally, and globally and to extract various concessions from the U.S. in negotiations on its nuclear program and various aid packages.

Such developments also improve North Korea’s military posture. U.S. and allied intelligence agencies assess that Pyongyang has already achieved nuclear warhead miniaturization, the ability to place nuclear weapons on its medium-range missiles, and the ability to reach the continental United States with a missile. North Korea also uses cyber warfare as a means of guerilla warfare against its adversaries and international financial institutions. This Index therefore assesses the overall threat from North Korea, considering the range of contingencies, as “testing” for level of provocation of behavior and “gathering” for level of capability.

A broad array of terrorist groups remain the most hostile of any of the threats to America examined in the Index. The primary terrorist groups of concern to the U.S. homeland and to Americans abroad are the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda and its branches remain active and effective in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and the Sahel of Northern Africa. Though no longer a territory-holding entity, ISIS also remains a serious presence in the Middle East, in South and Southeast Asia, and throughout Africa, threatening stability as it seeks to overthrow governments and impose an extreme form of Islamic law. Its ideology continues to inspire attacks against Americans and U.S. interests. Fortunately, Middle East terrorist groups remain the least capable threats facing the U.S., but they cannot be dismissed.

Just as there are American interests that are not covered by this Index, there may be additional threats to American interests that are not identified here. This Index focuses on the more apparent sources of risk and those that appear to pose the greatest threat.

Compiling the assessments of these threat sources, the 2023 Index again rates the overall global threat environment as “aggressive” and “gathering” in the areas of threat actor behavior and material ability to harm U.S. security interests, respectively, leading to an aggregated threat score of “high.”

2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength

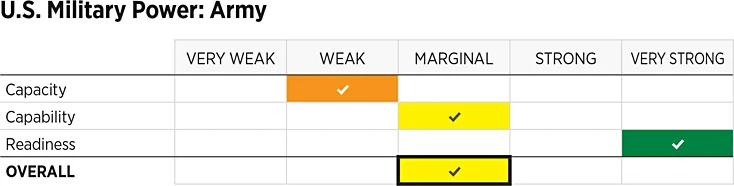

The Status of U.S. Military Power

Finally, we assessed the military power of the United States in three areas: capability, capacity, and readiness. We approached this assessment service by service as the clearest way to link military force size; modernization programs; unit readiness; and (in general terms) the functional combat power (land, sea, air, and space) that each service represents.

We treated the United States’ nuclear capability as a separate entity because of its truly unique characteristics and constituent elements, from the weapons themselves to the supporting infrastructure that is fundamentally different from the infrastructure that supports conventional capabilities. While not fully assessing cyber as we do the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force, we acknowledge the importance of new tools and organizations that have become essential to deterring hostile behavior and winning wars.

These three areas of assessment (capability, capacity, and readiness) are central to the overarching questions of whether the U.S. has a sufficient quantity of appropriately modern military power and whether military units are able to conduct military operations on demand and effectively.

As reported in all previous editions of the Index, the common theme across the services and the U.S. nuclear enterprise is one of force degradation caused by many years of underinvestment, poor execution of modernization programs, and the negative effects of budget sequestration (cuts in funding) on readiness and capacity in spite of repeated efforts by Congress to provide relief from low budget ceilings imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011. The services have undertaken efforts to reorient from irregular warfare to large-scale combat against a peer adversary, but such shifts take time and even more resources.

Because of the rising costs of fuel, munitions, and repair parts and the lack of qualified maintainers and maintenance facilities, much of the progress in regaining readiness that had been made in 2020 and 2021 has been lost in 2022. The forecast for 2023 is likewise gloomy given a proposed defense budget for FY 2023 that will not be sufficient to keep pace with ongoing and dramatic increases in inflation.

Experience in warfare is ephemeral and context-sensitive. Valuable combat experience is lost as servicemembers who individually gained experience leave the force, and it retains direct relevance only for future operations of a similar type: Counterinsurgency and adviser support operations in Iraq, for example, gained over the past two decades are fundamentally different from major conventional operations against a state like Iran or China.

Although portions of the current Joint Force are experienced in some types of operations, the force as a whole lacks experience with high-end, major combat operations of the sort being seen in Ukraine and toward which the U.S. military services have only recently begun to redirect their training and planning. Additionally, the force is still aged and shrinking in its capacity for operations even if limited quantities of new equipment like the F-35 Lightning II fighter are being introduced.

We characterized the services and the nuclear enterprise on a five-category scale ranging from “very weak” to “very strong,” benchmarked against criteria elaborated in the full report. These characterizations should not be construed as reflecting either the competence of individual servicemembers or the professionalism of the services or Joint Force as a whole; nor do they speak to the U.S. military’s strength relative to the strength of other militaries around the world in direct comparison. Rather, they are assessments of the institutional, programmatic, and material health or viability of America’s hard military power benchmarked against historical instances of use in large-scale, conventional operations and current assessments of force levels likely needed to defend U.S. interests against major enemies in contemporary or near-future combat operations.

Our analysis concluded with these assessments:

- Army as “Marginal.” The Army’s score remains “marginal” in the 2023 Index, and significant challenges that have arisen during the year call into question whether it will improve its status in the year ahead. Though the Army has sustained its commitment to modernizing its forces for great-power competition, its modernization programs are still in their development phase, and it will be a few years before they are ready for acquisition and fielding. In other words, the Army is aging faster than it is modernizing. It remains “weak” in capacity with only 62 percent of the force it should have. However, 25 of its 31 Regular Army BCTs are at the highest state of readiness, thus earning a readiness score of “very strong” and conveying the sense that the service knows what it needs to do to prepare for the next major conflict. Nevertheless, the Army’s internal assessment must be balanced against its own statements that unit training is focused on company-level operations rather than battalion or brigade operations. Consequently, how these “ready” brigade combat teams would actually perform in combat is an open question.

- Navy as “Weak.” This worrisome score, a drop from “marginal” assessed in the 2022 Index, is driven by problems in capacity (“very weak”) and readiness (“weak”). This Index assesses that the Navy needs a battle force of 400 manned ships to do what is expected of it today. The Navy’s current battle force fleet of 298 ships and intensified operational tempo combine to reveal a service that is much too small relative to its tasks. Contributing to a lower assessment is the Navy’s persistent inability to arrest and reverse the continued diminution of its fleet as adversary forces grow in number and capability. If its current trajectory is maintained, the Navy will shrink further to 280 ships by 2037. Current and forecasted levels of funding will prevent the Navy from altering its decline unless Congress undertakes extraordinary efforts to increase assured funding for several years.

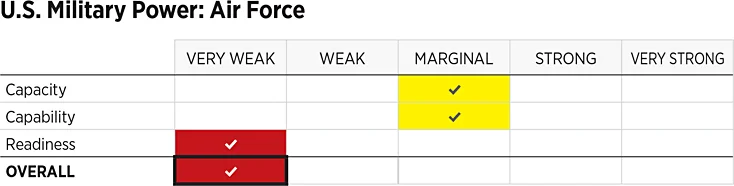

- Air Force as “Very Weak.” The Air Force has been downgraded once again, the second, time in the past two years. The Air Force was assessed as “marginal” in the 2021 Index but, with public reporting of the mission readiness and physical location of combat aircraft implying that it would have a difficult time responding rapidly to a crisis, fell to a score of “weak” in the 2022 Index. During FY 2022, the year assessed for this Index, problems with pilot production and retention, an extraordinarily small amount of time in the cockpit for pilots, and a fleet of aircraft that continues to age compounded challenges even more, leading to the current score of “very weak,” the lowest on our scale. The USAF currently is at 86 percent of the capacity required to meet a two-MRC benchmark, it is short 650 pilots, the average age of its fighter aircraft fleet is 32 years old, and pilots are flying barely more than once per week across all types of aircraft. New aircraft like the F-35 and KC-46 are being introduced, but the pace is too slow. Although there is a chance the Air Force might win a single MRC in any theater, there is little doubt that it would struggle in war with a peer competitor. Both the time required to win such a conflict and the attendant rates of attrition would be much higher than they would be if the service had moved aggressively to increase high-end training and acquire the fifth-generation weapon systems required to dominate such a fight.

- Marine Corps as “Strong.” The score for the Marine Corps was raised to “strong” from “marginal” in the 2022 Index and remains “strong” in this edition for two reasons: (1) because the 2021 Index changed the threshold for capacity, lowering it from 36 infantry battalions to 30 battalions in acknowledgment of the Corps’ argument that it is a one-war force that also stands ready for a broad range of smaller crisis-response tasks, and (2) because of the Corps’ extraordinary, sustained efforts to modernize (which improves capability) and enhance its readiness during the assessed year. Of the five services, the Corps is the only one that has a compelling story for change, has a credible and practical plan for change, and is effectively implementing its plan to change. However, in the absence of additional funding that would enable the Corps to maintain higher end strength while also pursuing its modernization and reorientation efforts, the Corps will reduce the number of its battalions even further to just 21, and this reduction will limit the extent to which it can conduct distributed operations as envisioned and replace combat losses (thus limiting its ability to sustain operations). Though the service remains hampered by old equipment in some areas, it has nearly completed modernization of its entire aviation component, is making good progress in fielding a new amphibious combat vehicle, and is fast-tracking the acquisition of new anti-ship and anti-air weapons. Full realization of its redesign plan will require the acquisition of a new class of amphibious ships, for which the Corps needs support from the Navy.

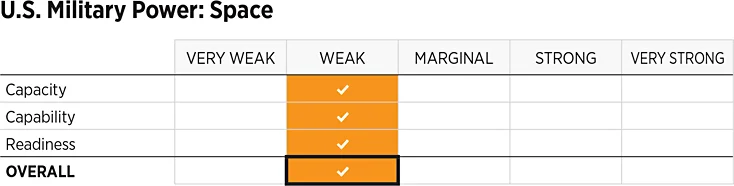

- Space Force as “Weak.” The mission sets, space assets, and personnel that have transitioned to the Space Force from the other services since its establishment in December 2019 and that have been added over the past two years have enabled the service to sustain its support to the Joint Force. However, there is little evidence that the USSF has improved its readiness to provide nearly real-time support to operational and tactical levels of force operations or that it is ready in any way to execute defensive and offensive counterspace operations to the degree envisioned by Congress when it authorized the creation of the Space Force. The majority of its platforms have exceeded their life span, and modernization efforts to replace them are slow and incremental. The service’s two counterspace weapons systems (Meadowlands and Bounty Hunter) cover only a fraction of the offensive and defensive capabilities required to win a conflict in space. Other counterspace systems are likely being developed or, like cyber, are already in play without public announcement. Nevertheless, the USSF’s current visible capacity is not sufficient to support, fight, or weather a war with a peer competitor.

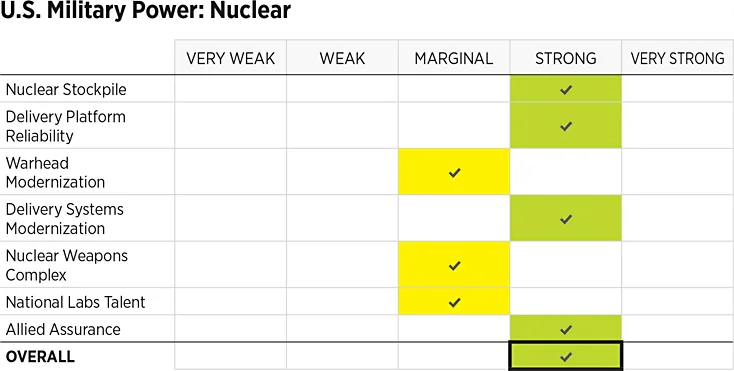

- Nuclear Capabilities as “Strong” but Trending Toward “Marginal” or Even “Weak.” This conclusion is sustained from the 2022 Index. The scoring for U.S. nuclear weapons must be considered in the context of a threat environment that is significantly more dangerous than it was in previous years. Until recently, U.S. nuclear forces needed to address one nuclear peer rather than two. Given senior leaders’ reassurances with respect to the readiness and reliability of U.S. nuclear forces, as well as the strong bipartisan commitment to modernization of the entire nuclear enterprise, this year’s Index retains its grade of “strong,” but only for now. U.S. nuclear forces face many risks that, without a continued commitment to a strong deterrent, could warrant a decline to an overall score of “marginal” or “weak.” The reliability of current U.S. delivery systems and warheads is at risk as they continue to age and the threat continues to advance. Iran, for example, has announced an ability to enrich uranium to 60 percent (90 percent is needed for a weapon), and Russia and China are aggressively expanding the types and quantities of nuclear weapons in their inventories. Nearly all components of the nuclear enterprise are at a tipping point with respect to replacement or modernization and have no margin left for delays in schedule. Future assessments will need to consider plans to adjust America’s nuclear forces to account for the doubling of peer nuclear threats. While capacity was not assessed this year, it is clear that the change in threat warrants a reexamination of U.S. force posture and the adequacy of current modernization plans. Failure to keep modernization programs on track while planning for a three-party nuclear peer dynamic could lead inevitably to a decline in the strength of U.S. nuclear deterrence.

In the aggregate, the United States’ military posture can only be rated as “weak.” The Air Force is rated “very weak,” the Navy and Space Force are “weak,” and the U.S. Army is “marginal.” The Marine Corps and nuclear forces are “strong,” but the Corps is a one-war force, and its overall strength is therefore not sufficient to compensate for the shortfalls of its larger fellow services. And if the United States should need to employ nuclear weapons, the escalation into nuclear conflict would seem to imply that handling such a crisis would challenge even a fully ready Joint Force at its current size and equipped with modern weapons. Additionally, the war in Ukraine, which threatens to destabilize not just Europe but the economic and political stability of other regions, shows that some actors (in this case Russia) will not necessarily be deterred from conventional action even though the U.S. maintains a strong nuclear capability. Thus, strong conventional forces of necessary size are essential to the ability of the U.S. to respond to emergent crises in areas of special interest.

The 2023 Index concludes that the current U.S. military force is at significant risk of not being able to meet the demands of a single major regional conflict while also attending to various presence and engagement activities. The force would probably not be able to do more and is certainly ill-equipped to handle two nearly simultaneous MRCs—a situation that is made more difficult by the generally weak condition of key military allies.

In general, the military services continue to prioritize readiness and have seen some improvement over the past few years, but modernization programs, especially in shipbuilding, continue to suffer as resources are committed to preparing for the future, recovering from 20 years of operations, and offsetting the effects of inflation. In the case of the Air Force, some of its limited acquisition funds are being spent on aircraft of questionable utility in high-threat scenarios while R&D receives a larger share of funding than efforts meant to replace quite aged aircraft are receiving. As observed in both the 2021 and 2022 editions of the Index, the services have normalized reductions in the size and number of military units, the forces remain well below the level needed to meet the two-MRC benchmark, and substantial difficulties in recruiting young Americans to join the military services are frustrating even modest proposals just to maintain service end strength.

Congress and the Administration took positive steps to stabilize funding in the latter years of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). This mitigated the worst effects of BCA-restricted funding, but sustained investment in rebuilding the force to ensure that America’s armed services are properly sized, equipped, trained, and ready to meet the missions they are called upon to fulfill will be critical. At present, the Administration’s proposed defense budget for FY 2023 falls far short of what the services need to regain readiness and to replace aged equipment, and Congress’s intention to increase the proposed budget by 5 percent accounts for barely half of the current rate of inflation, which is nearing 10 percent.

As currently postured, the U.S. military is at growing risk of not being able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests. It is rated as weak relative to the force needed to defend national interests on a global stage against actual challenges in the world as it is rather than as we wish it were. This is the logical consequence of years of sustained use, underfunding, poorly defined priorities, wildly shifting security policies, exceedingly poor discipline in program execution, and a profound lack of seriousness across the national security establishment even as threats to U.S. interests have surged.

Endnotes

[1] Though issued during President Donald J. Trump’s Administration, the 2018 NDS has not yet been superseded by a similar document, focused on the military, from the Administration of President Joseph R. Biden. However, the Biden Administration has released interim guidance in which it sets out the broad outlines and priorities of its national security agenda. In particular, President Biden’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance reiterates the same core national security interests and the same set of major competitor countries posing challenges to U.S. interests that the preceding Administration identified and places them in a global context wherein the U.S. military must be ready to handle several problems in geographically separated locations. See President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, The White House, March 2021, pp. 8–9, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf (accessed August 1, 2022).

[2] James Mattis, Secretary of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, p. 2. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf (accessed August 1, 2022).