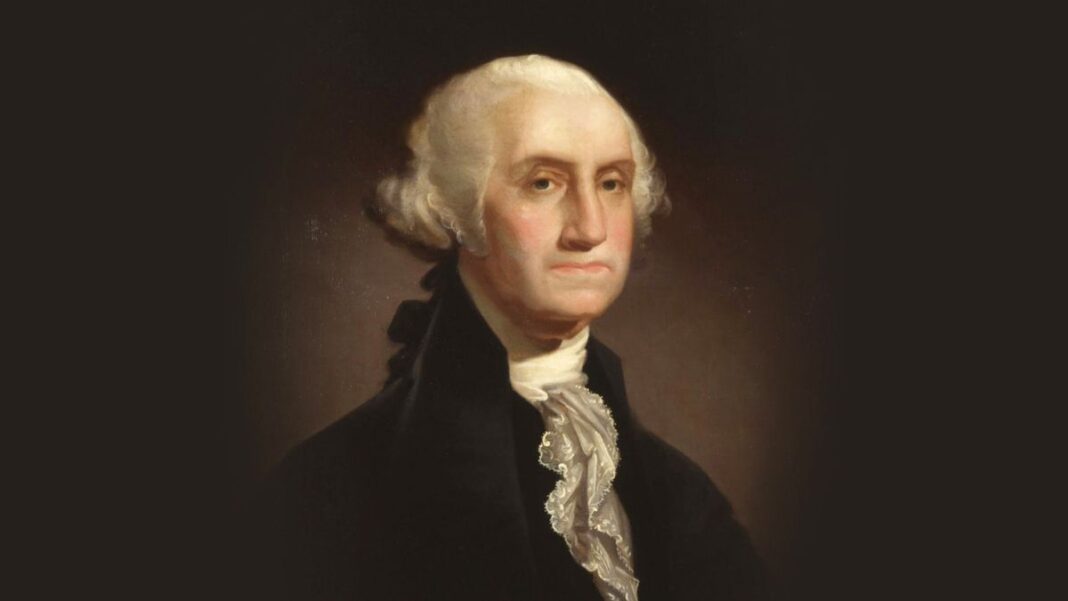

There is no better example of a great leader than that of George Washington. But too often, his leadership during the Revolutionary War and the first presidency is taken for granted. This month marks the 290th birthday of the Father of our Country.

Revolutionary War

In 1775, George Washington took command of the Continental Army. Although he often stated that he felt incapable of his position, he proved an excellent general. As commander-in-chief, Washington juggled countless duties. He arranged prisoner exchanges, replied to piles of correspondence, kept up with current politics, and campaigned for better conditions for his men. Besides fighting the enemy, the army battled extreme temperatures, smallpox, starvation, and even mutiny. Understandably Congress felt Washington was capable of anything and rarely answered his pleas for more supplies. Still, he continued to rely on that “bountiful Providence which has never failed us in the hour of distress.”

Washington considered his duty as commander-in-chief a heavy one. He confided to the President of Congress:

The reflection on my situation, and that of this army produces many an uneasy hour when all around me are wrapped in sleep. I have often thought how much happier I should have been, if, instead of accepting . . . [this] command . . . I had taken my musket on my shoulder and entered the ranks, or if I could have justified the measure to posterity and my own conscience, had retired to the back country, and lived in a wigwam.

Though Washington won few battles, his hit-and-run tactics bewildered the enemy. “As we go forward into the country the rebels fly before us,” wrote a British officer, “and when we come back they always follow us. ‘Tis almost impossible to catch them.” Meanwhile the Pennsylvania Journal applauded Washington by saying “he retreats like a general and acts like a hero.” Washington was unafraid in battle. During combat, Washington’s officers found themselves begging him not to expose himself so much.

In 1778 the British appeared to be trying to negotiate. General Washington was suspicious. Though eager for peace he wanted independence even more:

The enemy are beginning to play a game more dangerous than their efforts by arms, . . . which threatens a fatal blow to American independence, and to her liberties . . . : They are endeavoring to ensnare the people by specious allurements of peace . . . . A peace on the principles of dependence, however limited, after what has happened, would be to the last degree dishonorable and ruinous . . . . Nothing short of independence, it appears to me, can possibly do.

“Banish these thoughts”

Another event occurred when in May of 1782 Colonel Lewis Nicola offered to make Washington King of America. Washington responded with astonishment:

Be assured Sir, no occurrence in the course of the war, has given me more painful sensations . . . I am much at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address which to me seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country. . . .[Y]ou could not have found a person to whom your schemes are more disagreeable . . . .Let me conjure you then, if you have any regard for your country, concern for yourself or posterity, or respect for me, to banish these thoughts from your mind . . . .

The war over, General Washington resigned his commission, never once pointing to himself for the victory, but attributing the success to God. In 1788 Alexander Hamilton wrote the general broaching the possibility of Washington’s becoming the first President. Washington’s friends, country, and the need for greater unity in the nation convinced him to accept the office.

Washington’s Political Principles

Washington believed in an energetic government but was careful not to abuse presidential power. He reasoned that America’s great political freedom rested on representation of the people and a good executive. Jefferson observed, “He sincerely wished the people to have as much self-government as they were competent to exercise themselves.” John Adams remarked that President Washington was not influenced by anyone when making decisions. “I walk on untrodden ground,” Washington realized. “There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.”

In his first annual message to Congress President Washington spoke of providing for the common defense—a critical issue to Washington. “A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined,” he told Congress. He knew that a nation which stayed prepared for war would always be a peaceful one. As President he reinforced this statement by vetoing a bill meant to reduce the cavalry.

Whiskey Rebellion

In 1794 the Whiskey Rebellion tested Washington’s leadership and the resolve of the new government. The rebellion was begun by Pennsylvania farmers who disliked a specific tax placed on liquor. While Washington gave the farmers a chance to stop their unlawful actions, he argued that “the very existence of government, and the fundamental principles of social order, are materially involved in the issue.” He called out the militia, convinced that as President his duty was “to take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” The rebellion blew over quickly—the farmers surrendered in the face of thousands of militia.

War?

A further crucial stage in Washington’s presidency was his decision to remain neutral while France and England were at war. Many Americans wanted to remain loyal to the ally (France) that had helped the United States gain her independence. But Washington chose to stay neutral. In a letter to Gouverneur Morris he wrote:

It is well known that peace has been . . . the order of the day with me, since the disturbances in Europe first commenced. My policy has been and will continue to be, while I have the honor to remain in the administration of the government, to be upon friendly terms with, but independent of, all the nations of the earth. He went on to say, “By a firm adherence to these principles . . . I have brought on myself a torrent of abuse in the factious papers in this country. . . .”

Criticism

Sadly this was true; during his presidency Washington was not as revered as he had been during the war. He could not believe “that every act of my administration would be tortured, and the grossest, and most insidious misrepresentation of them be made.” One day in particular the criticism took a toll on Washington, as Jefferson recalled:

[He] defied any man on earth to produce one single act of his since he had been in the government which was not done on the purest motives, [said] that he had never repented but once having slipped the moment of resigning his office, and that was every moment since, and that by God he had rather be in his grave than in his present situation; that he had rather be on his farm than to be made emperor of the world, and yet that they were charging him with wanting to be king.

However much he was criticized by the public and weighed down by the cares of office, Washington could be comforted by one thought: “The acts of my administration will appear when I am no more, and the intelligent and candid part of mankind will not condemn my conduct without recurring to them.”

Looking over key moments during the war and his presidency, we see that George Washington was a great leader because of his great qualities. Two facts about his character stand out—he never once asked for any of the positions he filled, and he never abused the trust of his countrymen.

Bibliography:

Allen, W.B., ed. George Washington: A Collection. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1988.

Allison, Andrew M., Jay A. Parry, and W. Cleon Skousen. The Real George Washington, 3rd ed. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Lorant, Stefan. The Presidency. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952.

Taylor, Tim. The Book of Presidents. New York: Arno Press, 1972.