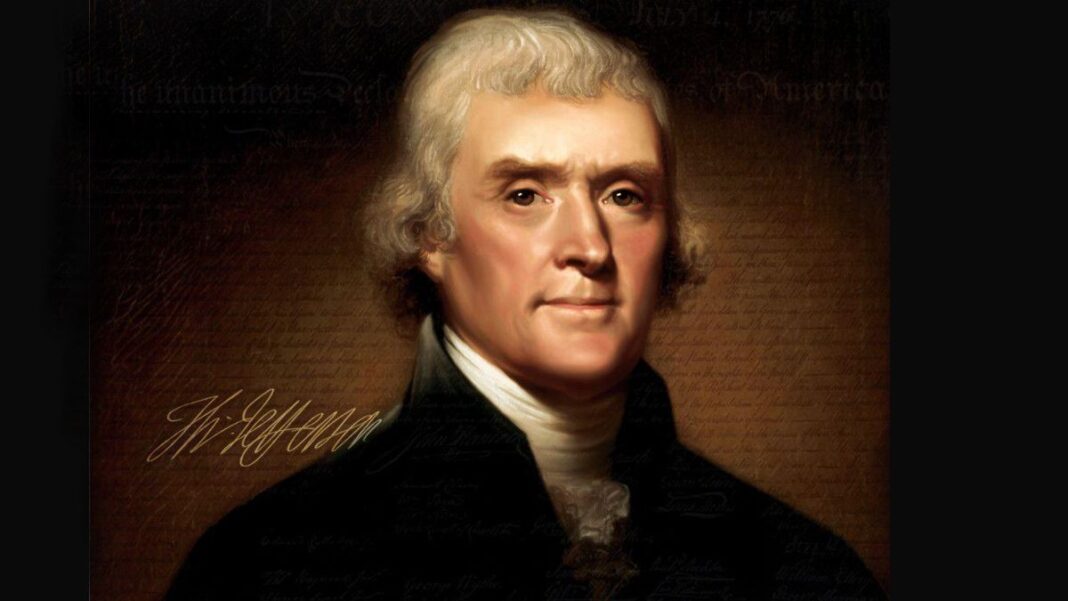

Thomas Jefferson is most renowned for his being the author of the Declaration of Independence. But when he had the chance to put his philosophy into action as President, his great leadership has frequently been overlooked.

Jeffersonian Politics

In the late 1790s Jefferson emerged as the leader of the Republican party. He believed Americans should remain attached to the “principles of 1776”—something he felt the Federalist party did not do. When Jefferson replaced the Federalists by becoming President in 1801, some people, misjudging Jefferson’s character, expected a revolution. These individuals were calmed by his inaugural address, which stressed the importance of and need for unity, advocating “a wise and frugal government.” His goal, he explained, was to put America back on Republican principles.

Throughout his life, Thomas Jefferson supported the sovereignty of the people, local self-government, strict interpretation of the Constitution, a well-trained militia and a small standing army, and rotation of office. His character was most prominently stamped with a great faith in mankind and a willingness to let the people rule. His biggest fear was of monarchy and tyranny. “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man,” he declared.

Praise and Criticism

An individual in Jefferson’s day summed up the current administration by writing—“Never was there an administration more brilliant than that of Mr. Jefferson up to this period. Taxes repealed; the public debt amply provided for . . . sinecures abolished; Louisiana acquired; public confidence unbounded.”

Even though Jefferson was a popular President, he faced criticism, coming mostly from a disgruntled Republican journalist named James Callender. When Callender started writing for a Federalist newspaper, he began slurring Jefferson’s moral character. Jefferson made no reply to these attacks, saying he would feel guilty if he even took notice of them. A free press was always defended by Jefferson: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

Louisiana Purchase

By 1803 the land called Louisiana had become French property, including a port important to America—New Orleans. Jefferson, attempting to be diplomatic, began negotiations with Napoleon for the port, only to be astonished when Napoleon was willing to sell all of Louisiana. However, Jefferson was concerned about whether the Constitution authorizes this type of acquisition:

The Constitution has made no provision for our holding foreign territory, still less for incorporating foreign nations into our Union. The executive, in seizing the fugitive occurrence which so much advances the good of their country, have done an act beyond the Constitution. . . . It is the case of a guardian investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory, and saying to him when of age, [“]I did this for your good; I pretend to no right to bind you; you may disavow me, and I must get out of the scrape as I can; I thought it my duty to risk myself for you.[“] But we shall not be disavowed by the nation, and their act of indemnity will confirm and not weaken the Constitution, by more strongly marking out its lines.

Jefferson, wishing to expand the U.S., took advantage of this great opportunity and accepted Napoleon’s offer. The nearly 512 million acres (five time the size of France) more than doubled the U.S. for fifteen million dollars. Jefferson considered the purchase the greatest act of his presidency.

Embargo Act

Jefferson, in his second inaugural address, reminded his countrymen that “I shall need. . . the favor of that Being in whose hands we are.” Indeed, during Jefferson’s second term it seemed as if war with Great Britain were certain. One reason war was a possibility was because of Great Britain’s searching American ships under the pretext of locating deserters. Thousands of American sailors were forced to serve in the Royal Navy (this was called impressment). There was also the incident involving the British ship Leopard, which opened fire on the American ship Chesapeake and proceeded to search it for “deserters.” These factors combined to produce clamors for war with England. Jefferson remarked he had not seen the U.S. in such a state since the days of the Battle of Lexington.

Still President Jefferson remained determined to prevent war. In March of 1807 he refused to accept a treaty negotiated with Great Britain because it did not include a provision regarding impressment or the seizure of American ships. A few months later he ordered all British warships to leave American waters. However, conditions only worsened. “We have to choose between the alternatives of embargo and war,” Jefferson insisted. He asked Congress to pass the Embargo Act, which proposed a total stop on American shipping abroad. He realized the embargo would be uncomfortable for the U.S., but he intended to display to foreign nations the firmness of the U.S. government; and to the public, the need for unity in times of crisis.

At first the nation supported the President’s decision, but before long it was evident that rather than affecting England or France the embargo crippled the U.S. In 1809 the Non-Intercourse Act was signed, repealing the embargo and reopening trade with all nations but Great Britain and France.

Jefferson versus the Judiciary

Jefferson was always wary of the federal judiciary: “We find the judiciary, on every occasion, still driving us into consolidation.” In 1803 a precedent-setting court-case, Marbury v. Madison, authorized all federal courts to review the constitutionality of legislation. This was called judicial review. Jefferson opposed this practice, thinking it “a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.” He felt there were not enough checks on the judicial branch and believed judges were conspiring to undermine the independent rights of the states. As a result, he lobbied for an amendment which would restrain the judiciary. To Abigail Adams Jefferson explained:

Nothing in the Constitution has given them [judges] a right to decide for the executive, more than to the executive to decide for them. Both magistrates are equally independent in the sphere of action assigned to them. . . . But the opinion which gives to the judges, the right to decide what laws are constitutional and what not, not only for themselves in their own sphere of action, but for the legislative and executive also in their spheres, would make the judiciary a despotic branch.

Conclusion

In contrast to his drafting of the illustrious Declaration of Independence, Jefferson’s presidency seems rather unnoticed. The overwhelming confidence he placed in the trust of the people also underemphasized his own achievements. Thomas Jefferson’s leadership should be emphasized because he was content to take care of the country without attempting to do anything unnecessary. Furthermore, his caution towards all forms of power made him a great leader, and one to be trusted.

Bibliography:

Allison, Andrew M., M. Richard Maxfield, K. DeLynn Cook, and W. Cleon Skousen. The Real Thomas Jefferson. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Athearn, Robert G. The American Heritage Illustrated History of the United States, Vol. IV: A New Nation. New York: Dell Publishing Company, 1963.

Freidel, Frank. Our Country’s Presidents. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1966.

Lorant, Stefan. The Presidency. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952.

Skousen, W. Cleon. The Making of America, 3rd ed., revised. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2007.

Taylor, Tim. The Book of Presidents. New York: Arno Press, 1972.