Much has been remanded back to the District Court to decide—for now.

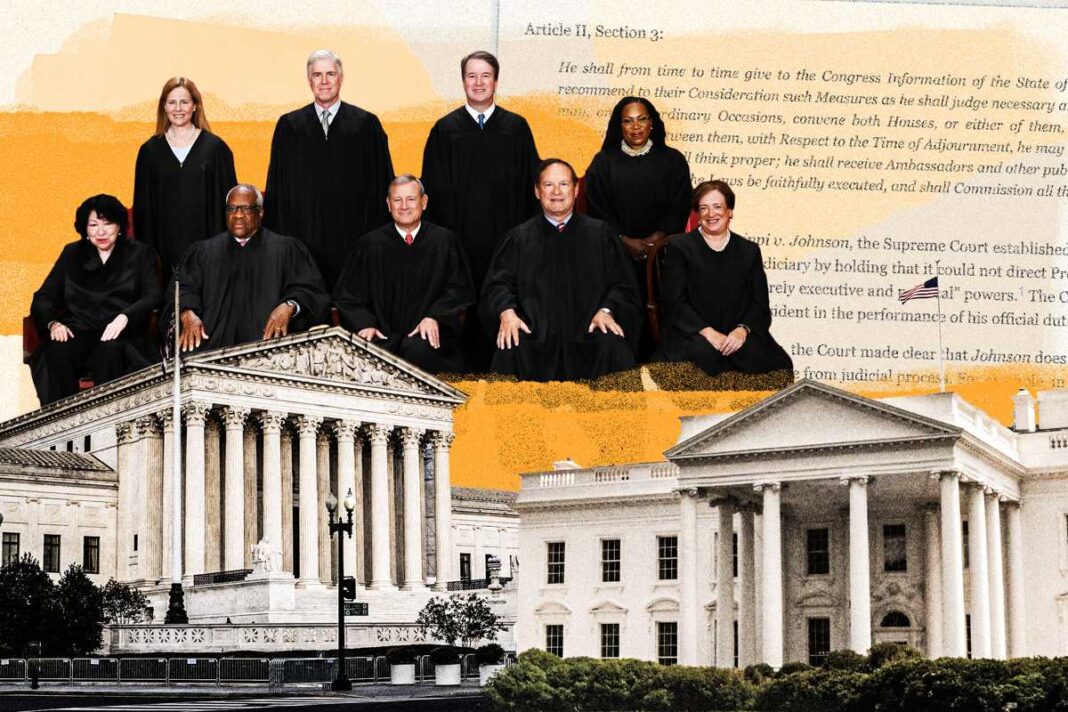

On July 1, the Supreme Court ruled that presidents and former presidents enjoy “absolute immunity” from criminal prosecution for “conduct within his exclusive sphere of constitutional authority,” setting guidelines for which acts in former President Donald Trump’s federal election case can remain in the indictment but leaving large amounts of litigation for the district court.

The case, which has been on hold since December 2023, is unlikely to proceed to trial before the November election but may soon see a flurry of legal activity.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion, with Justice Clarence Thomas adding his own concurring opinion. Justice Amy Coney Barret concurred in part, noting several lines of legal disagreement with the majority. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, who also penned a separate dissent.

Trump Case Will Continue

The Supreme Court has given the case back to the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia, where Judge Tanya Chutkan will have to determine whether several of President Trump’s actions in the indictment were, essentially, official or unofficial.

“Despite the unprecedented nature of this case, and the very significant constitutional questions that it raises, the lower courts rendered their decisions on a highly expedited basis,” the opinion reads.

Both the district and circuit courts completely rejected assertions of presidential immunity, so there has been no briefing on whether actions in the indictment were official or unofficial.

“That categorization raises multiple unprecedented and momentous questions,” the opinion reads.

When Judge Chutkan rejected the motion to dismiss based on presidential immunity last year, the appeals court fast-tracked the appeal, rejected the motion, and also fast-tracked the appeal process to the Supreme Court.

All case proceedings were paused in the meantime, and Judge Chutkan had taken the case—originally scheduled for March 4—off her calendar. At the time, the judge still had a number of motions to rule on, including a major ruling on what evidence and arguments could be used at trial.