Lawless Elections Are an Existential Threat to Democracy

Conclusive evidence has just been produced that shows the 2020 election in Wisconsin was managed recklessly and lawlessly. While there are still many important questions to be addressed and investigated, we now know that changes must be made before the next election.

The non-partisan Legislative Audit Bureau (LAB) recently released its long-awaited report (here and below) following a process in which members of both parties have consistently expressed confidence. The audit, which was thorough but not comprehensive, identified no fewer than six instances in which state and local election officials “did not comply with statutes” – otherwise known as “breaking the law.”

This news should shock the nation and embarrass Wisconsin officials who participated in or condoned the lawlessness. No less an authority than the United State Constitution assigns responsibility for managing our elections to the state legislatures, yet unelected officials in municipal clerk’s offices and the Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC) took it upon themselves to ignore established laws and unilaterally invent new rules.

In the aftermath of those explosive revelations, however, the most common headline was “Wisconsin audit finds elections are ‘safe and secure.’” Another headline declared, “No findings of fraud, but Wisconsin election audit questions some of the guidance clerks relied on in 2020.”

These headlines make it seem as though Wisconsin voters have nothing to worry about. And that’s exactly the impression the left wants readers to come away with, especially as it seeks to thwart ongoing investigations and election reform efforts in Wisconsin and other states. But responsible citizens need to look beyond the headlines and hold their government officials accountable for the brazen violations of law that the LAB documented.

By Phill Kline

Read Full Article on Townhall.com

The Real Story – OAN Wisconsin Audit Results with Phill Kline

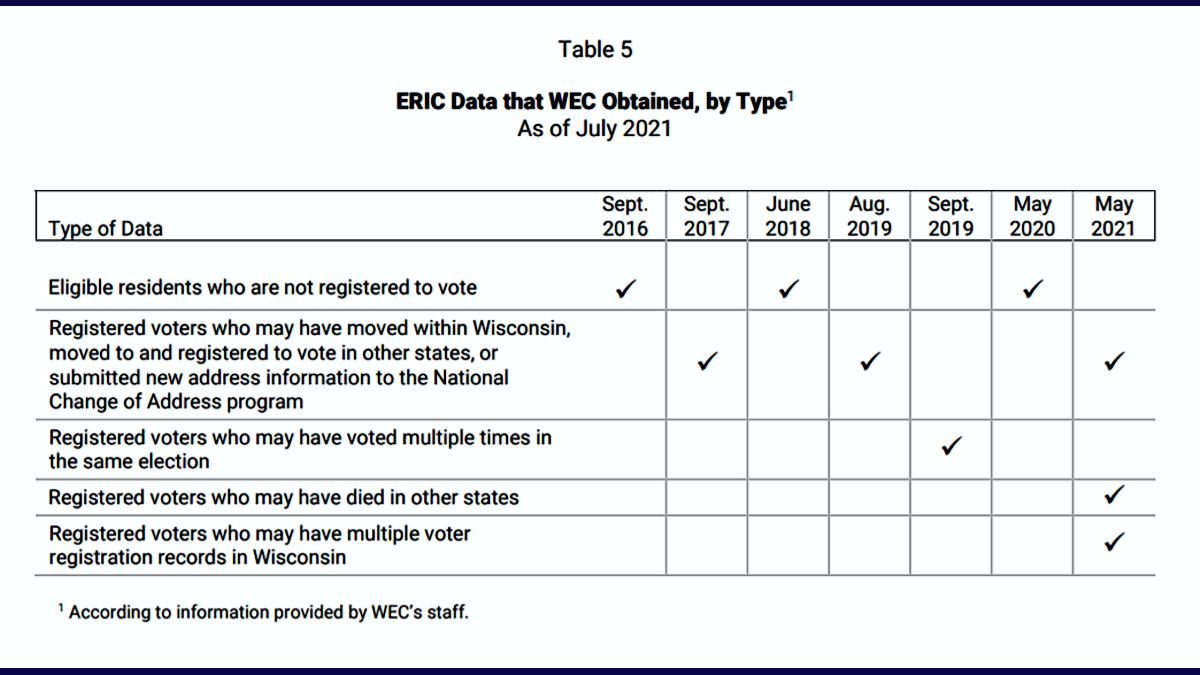

Table 5

ERIC Data that WEC Obtained, by Type1

As of July 2021

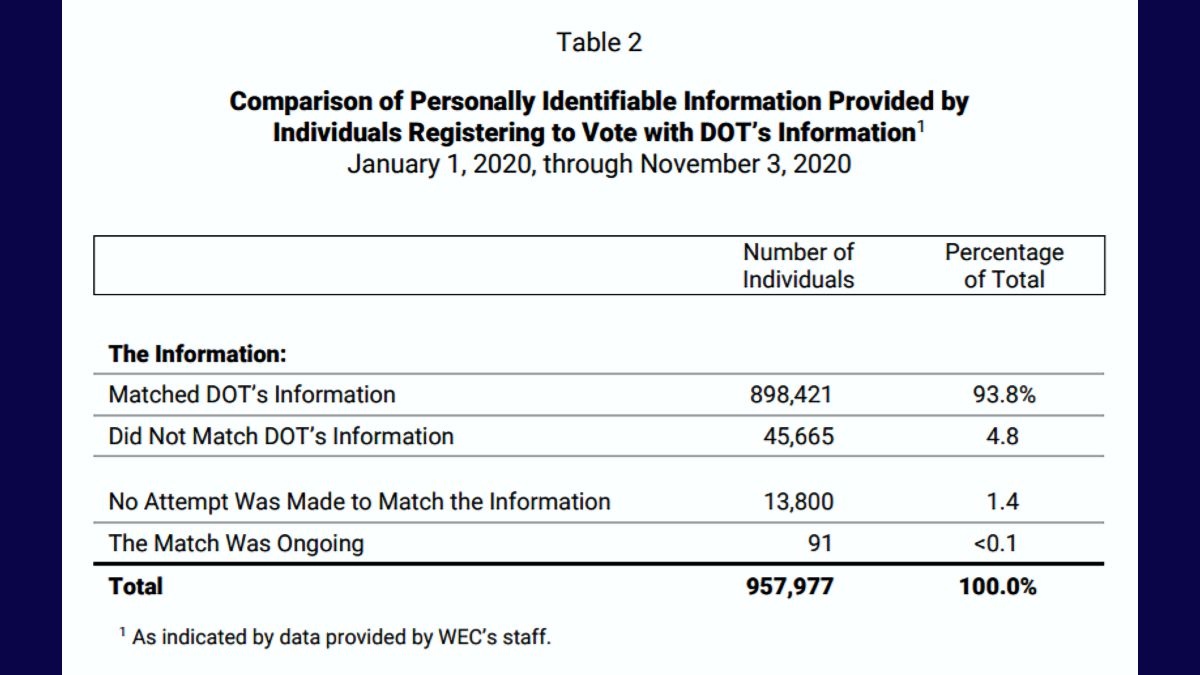

Comparison of Personally Identifiable Information Provided by

Individuals Registering to Vote with DOT’s Information1

January 1, 2020, through November 3, 2020

Elections Administration Report Introduction (Read Full PDF Report Below)

The Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC) is responsible for ensuring compliance with state and federal election laws, and county and municipal clerks administer elections. Statutes require WEC to provide training and guidance to municipal clerks in the state’s 1,849 municipalities. Statutes also require WEC to design and maintain the state’s electronic voter registration system, which is known as WisVote; maintain the MyVote Wisconsin website, through which individuals may register to vote and obtain absentee ballots and other election-related information; and approve electronic voting equipment before it can be used in Wisconsin. Statutes specify how individuals can submit complaints pertaining to elections administration issues to WEC. WEC was created by 2015 Wisconsin Act 118, which was enacted in December 2015, and began operation on June 30, 2016. WEC replaced the Government Accountability Board (GAB), which was abolished by Act 118.

WEC includes six commissioners who serve for five-year terms, including:

- one commissioner appointed by the Senate Majority Leader;

- one commissioner appointed by the Senate Minority Leader;

- one commissioner appointed by the Assembly Speaker;

- one commissioner appointed by the Assembly Minority Leader; and Introduction

- two commissioners appointed by the Governor, with the advice and consent of the Senate. These two commissioners must have formerly served as county or municipal clerks. The Governor nominates one individual from each of the lists provided by the two political parties that received the most votes for President.

Appendix 1 lists the six WEC commissioners as of October 2021 and indicates how each commissioner was appointed.

WEC is statutorily required to appoint an administrator with the advice and consent of the Senate. This administrator, who serves as the state’s chief election officer, performs the duties assigned by WEC and appoints other staff as needed to help carry out these duties. Statutes require WEC’s staff to be nonpartisan. WEC has delegated to the administrator limited authority to act without its involvement. In February 2020, WEC delegated the authority for the administrator to exempt municipalities from polling place accessibility requirements, exempt municipalities from using electronic voting equipment, and execute certain contracts up to $100,000. WEC also delegated the authority for the administrator to take specified actions in consultation with its chairperson, including when considering certain complaints.

Elections are administered by local election officials. Figure 1 shows the key statutory responsibilities of local election officials, including county clerks, municipal clerks, chief election inspectors, and election inspectors. The City of Milwaukee Election Commission, rather than the municipal clerk, administers elections in the City of Milwaukee.

The Legislative Audit Bureau has previously completed audits of elections administration issues, including Complaints Considered by the Government Accountability Board (report 15-13), Government Accountability Board (report 14-14), Compliance with Election Laws (report 07-16), and Voter Registration (report 05-12).

After the General Election on November 3, 2020, questions were raised about elections administration issues, including compliance with election laws, the use of electronic voting equipment, and complaints filed with WEC and clerks. On February 11, 2021, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee directed us to evaluate elections administration issues, including:

efforts by WEC to comply with election laws, including by working with clerks to ensure voter registration data include only eligible voters, and by providing training and guidance to clerks;

- efforts by clerks to comply with election laws, including by administering elections, processing absentee ballots, and performing recount responsibilities, as well as the observations and concerns of clerks regarding elections administration;

- the use of electronic voting equipment, including the methodology and results of WEC’s most-recent statutorily required post-election audit and the actions taken as a result of this audit; and

- General Election–related complaints filed with WEC and clerks, as well as how those complaints were addressed.

To complete this evaluation of issues pertaining to the November 2020 General Election:

- We contacted eight groups that are involved with elections administration issues. These groups are listed in Appendix 2.

- We reviewed statutory provisions pertaining to elections administration and WEC’s administrative rules. We contacted WEC’s staff and reviewed their written policies and procedures, the minutes and materials associated with WEC’s meetings, and the written guidance provided by WEC and its staff to municipal and county clerks.

- In April 2021, we invited all six WEC commissioners to discuss elections administration issues. Two commissioners spoke with us, and one other commissioner provided written information.

In April 2021, we surveyed all 1,835 municipal clerks and all 72 county clerks to obtain their perspectives on various issues pertaining to the General Election. A total of 879 municipal clerks (47.9 percent) and 59 county clerks (81.9 percent) responded to our survey.

- We contacted a total of 179 clerks in 61 counties, including 157 municipal clerks and 22 county clerks, to obtain additional information about elections administration issues. The locations of these clerks are listed in Appendix 3.

- We analyzed WisVote data pertaining to voter registration records and absentee ballots cast in the General Election.

- We physically reviewed 14,710 absentee ballot certificates, which are typically the envelopes in which individuals return absentee ballots. We attempted to review certificates in 30 municipalities, including the 10 municipalities where the most absentee ballots were cast in the General Election, the 10 municipalities where the highest proportions of absentee ballots were cast in that election, and 10 municipalities we selected randomly from counties other than those in which the first 20 municipalities were located. However, the City of Madison clerk declined to allow us to physically handle the certificates. The clerk indicated that the clerk’s office is responsible for maintaining the chain of custody of election records and ensuring these records are not inadvertently altered or damaged. As a result, we examined certificates in 29 municipalities. The results of our review are shown in Appendix 4.

- We reviewed a total of 1,233 Election Day forms completed by poll workers for the November 2020 General Election, including 571 forms completed by poll workers in 319 municipalities that we randomly selected and 662 forms completed by poll workers in 39 municipalities that had central count locations. On these forms, poll workers recorded information such as the numbers of absentee ballots that were remade and rejected. The results of our review are shown in Appendix 5.

- We reviewed a total of 175 statutorily required tests that municipal clerks had completed before the General Election for electronic voting equipment used in 25 municipalities. The results of our review are shown in Appendix 6.

We reviewed all 45 sworn, written complaints pertaining to the General Election that were filed with WEC as of late-May 2021, and we reviewed 1,521 election-related concerns that individuals provided through forms on WEC’s website from January 2020 through mid-April 2021.

- We assessed 26 reports that expressed general concerns about how the General Election was conducted and that were made to our office’s Fraud, Waste, and Mismanagement Hotline. Few reports provided information pertaining to specific municipalities or issues. One report expressed concerns about a post-election investigation. We also assessed one complaint forwarded to us by a legislative office by speaking with two municipal clerks, but we did not find information to substantiate the issues in this complaint.

- We reviewed information about the recount costs that Dane and Milwaukee counties submitted to WEC after the General Election.

- We reviewed information from other states about various elections administration issues, including ballot drop boxes, signature verification on absentee ballot certificates, indefinitely confined individuals, post-election audits, and recount costs.

Based on our audit work:

- we make 30 recommendations for improvements, which are located throughout the report and comprehensively listed in Appendix 7; and

- we include 18 issues for legislative consideration, which are located throughout the report and comprehensively listed in Appendix 8.

Because our audit was not approved until three months after the November 2020 General Election, we did not directly observe Election Day practices, including how poll workers processed ballots and how electronic voting equipment operated. The U.S. Department of Justice indicated that election officials are responsible for retaining and preserving election records, regardless of who physically possesses them. In part as a result of this guidance from the Department of Justice, the City of Madison clerk did not allow us to physically handle election records. In addition, county clerks indicated that we would not be able to handle ballots for Milwaukee County and the Town of Little Suamico. Combined, the City of Madison, Milwaukee County, and the Town of Little Suamico accounted for 623,700 of the 3.3 million ballots cast in the November 2020 General Election (18.9 percent). Therefore, to complete our audit we relied on available evidence we were able to access, including WisVote data, absentee ballot certificates that we could physically handle, other election records, and information provided to us by municipal clerks, county clerks, WEC’s staff, and other individuals.

Statutes require us at all times to observe the confidential nature of any audit being performed. As a result, we completed our audit independently from legislators, WEC, and all other individuals and organizations. Although we typically allow an audited entity the opportunity to review our draft audit report and respond in writing to it, we did not do so for this report. Because we contacted a total of 179 clerks, sharing the draft audit report with so many individuals would have compromised the report’s confidentiality. In addition, because WEC’s administrator has limited authority to act without WEC’s involvement, we would have needed to provide our confidential draft audit report to WEC for its consideration. Statutes allow governmental bodies such as WEC to convene in closed session only for specified purposes, none of which pertains to reviewing draft audit reports. Thus, to preserve the statutorily required confidentiality of our audit until its completion, we did not provide WEC with an opportunity to review a confidential draft audit report and respond in writing to this report prior to its release.