This killer light beam can be pinpointed to target something smaller than a single cell.

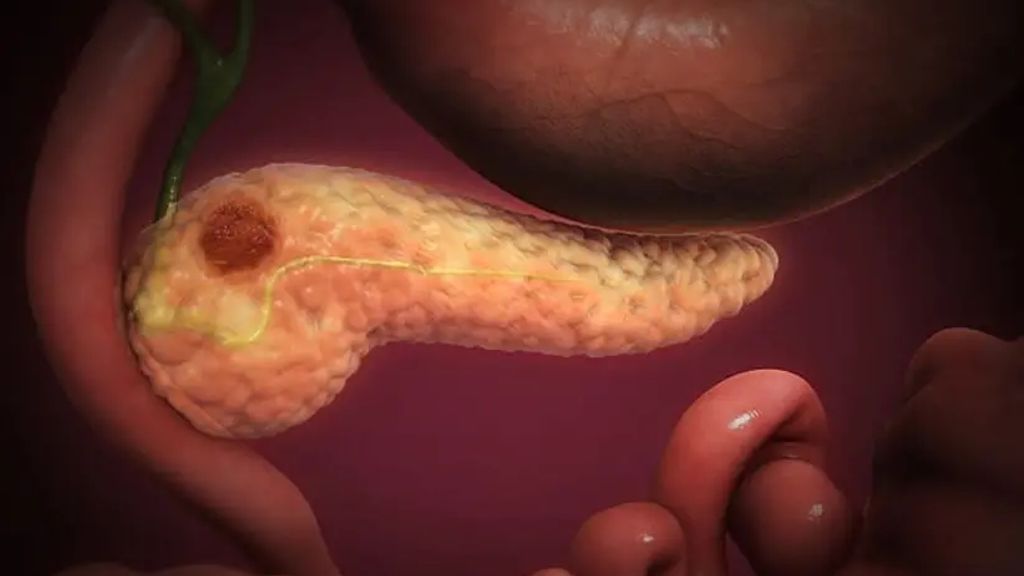

Cancer treatments that aim to destroy deadly cells often cause damage and pain as they wreak havoc on neighboring cells and tissues. However, scientists have discovered a new method of targeting harmful cells using light for precise destruction, according to a recent study.

“Usually treatments for cancer use pharmacological induction to kill the cells, but those chemicals tend to diffuse throughout the tissues and it’s hard to contain to a precise location,” said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign biochemistry professor and study leader Kai Zhang in a press release. “You get a lot of unwanted effects.”

The researchers deploy optogenetics, an approach that uses optical systems to control cell functions, to focus a light beam on a target smaller than one cell.

“That is how we can use light to very precisely target a cell and turn on its death pathway,” Mr. Zhang said in the press release.

In addition to killing the cancer cell, another intended outcome is to trigger the immune system to respond to the light. Mr. Zhang said that the ruptured cells release cytokines, a type of small protein, attracting white blood cells that help the immune system fight infection. By killing cancer cells, the researchers hope to train T-cell white blood cells to recognize and attack the cancer, Mr. Zhang said.

The researchers made the cells respond to light by borrowing a light-activated gene from plants and inserting it into intestine cell cultures. They then attached those genes to the genes for a protein, RIPK3, that regulates necroptosis, a form of cell death caused by various stimuli.

Teak-Jung Oh, a graduate student and the paper’s first author, said the light activation process causes the RIPK3 proteins to cluster together, mimicking the natural death pathway.

“Understanding the cell signaling pathway for necroptosis is especially important because it has been known to be involved with diseases like neurodegenerative disease and inflammatory bowel disease,” said Mr. Oh. “Knowing how necroptosis affects progression in these diseases is important. And if you don’t know the molecular mechanisms, you don’t really know what to target to slow the progression.”

The study was published in the July issue of the Journal of Molecular Biology.

By Huey Freeman