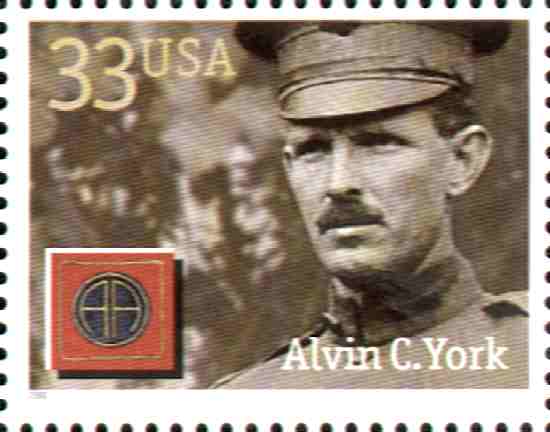

On October 8, 1918, Sgt. Alvin C. York almost single-handedly killed 25 German soldiers and captured 132 others.

By Dr. Michael Birdwell ~ Known as the greatest [American] hero of World War I, York avoided profiting from his war record before 1939. Born December 13, 1887 in a two-room dogtrot log cabin in Pall Mall, Tennessee, and raised in a rural backwater in the northern section of Fentress County, York was a semi-skilled laborer when drafted in 1917. Quite literally having never traveled more than fifty miles from his home, York’s war experience served as an epiphany awakening him to a more complex world.

The third oldest of a family of eleven children, the York family eked out a hardscrabble existence of subsistence farming supplemented by hunting, and York became a competent marksman at an early age. Living in a region that saw little need for education, York had a grand total of nine-months schooling at a subscription school he attended in his youth. York’s father, William York (who died in 1911), also acted as a part time blacksmith to provide some extra income for the family. Prior to the advent of the World War, York was employed as a day laborer on the railroad near Harriman. As a result, York had little experience with managing money and later suffered from chronic fiscal problems. (York spent money when he had it, gave it away to other people who he believed needed it, and invested poorly).

As York came of age he earned a reputation as a deadly accurate shot and a hell raiser. Drinking and gambling in borderline bars known as “Blind Tigers,” York was generally considered a nuisance and someone who “would never amount to anything.” That reputation underwent a serious overhaul when York experienced a religious conversion in 1914. In that year two significant events occurred: his best friend, Everett Delk, was killed in a bar fight in Static, Kentucky; and he attended a revival conducted by H.H. Russell of the Church of Christ in Christian Union. Delk’s senseless death convinced York that he needed to change his ways or suffer a fate similar to his fallen comrade, which prompted him to attend the prayer meeting.

A strict fundamentalist sect with a following limited to three states–Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee–the Church of Christ in Christian Union espoused a strict moral code which forbade drinking, dancing, movies, swimming, swearing, popular literature, and moral injunctions against violence and war. Though raised Methodist, York joined the Church of Christ in Christian Union and in the process convinced one of his best friends, Rosier Pile, to join as well. Blessed with a melodious singing voice, York became the song leader and a Sunday School teacher at the local church. Rosier Pile went on to become the church’s pastor. The church also brought York in contact with the girl who would become his wife, Gracie Williams.

By most accounts, York’s conversion was sincere and complete. He quit drinking, gambling, and fighting. When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, York’s new found faith would be tested. York received his draft notice from his friend, the postmaster and pastor, Rosier Pile, on June 5, 1917, just six months prior to his thirtieth birthday. Because of the Church of Christ in Christian Union’s proscriptions against war, Pile encouraged York to seek conscientious objector status. York wrote on his draft card: “Dont [sic] want to fight.” When his case came up for review it was denied at both the local and the state level because the Church of Christ in Christian Union was not recognized as a legitimate Christian sect.

Though a would-be conscientious objector, drafted at age thirty, York in many ways typified the underprivileged, undereducated conscript who traveled to France to “keep the world safe for democracy.” With great reservations, York embarked for Camp Gordon, Georgia to receive his basic training. A member of Company G in the 328th Infantry attached to the 82nd Division (also known as the “All American Division) York established himself as a curiosity–an excellent marksman who had no stomach for war. After weeks of debate and counseling, York relented to his company commander, G. Edward Buxton, that there are times when war is moral and ordained by God, and he agreed to fight.

York’s role as hero went beyond his exploit in the Argonne and continues to both inspire and confound. On October 8, 1918, Corporal Alvin C. York and sixteen other soldiers under the command of Sergeant Bernard Early were dispatched before sunrise to take command of the Decauville railroad behind Hill 223 in the Chatel-Chehery sector of the Meuse-Argonne sector. The seventeen men, due to a misreading of their map (which was in French not English) mistakenly wound up behind enemy lines. A brief fire fight ensued which resulted in the confusion and the unexpected surrender of a superior German force to the seventeen soldiers. Once the Germans realized that the American contingent was limited, machine gunners on the hill overlooking the scene turned the gun away from the front and toward their own troops. After ordering the German soldiers to lie down, the machine gun opened fire resulting in the deaths of nine Americans, including York’s best friend in the outfit, Murray Savage. Sergeant Early received seventeen bullet wounds and turned the command over to corporals Harry Parsons and William Cutting, who ordered York to silence the machine gun. York was successful and when all was said and done, nine men had captured 132 prisoners.

York at Chatel

Chehery After the War

That York deserves credit for his heroism is without question. Unfortunately, however, his exploit has been blown out of proportion with some accounts claiming that he silenced thirty-five machine guns and captured 132 prisoners single-handedly. York never claimed that he acted alone, nor was he proud of what he did. Twenty-five Germans lay dead, and by his accounting, York was responsible for at least nine of the deaths. Only two of the seven survivors were acknowledged for their participation in the event; Sergeant Early and Corporal Cutting were finally awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1927.

York’s war exploit typified that of the nineteenth century American hero. He appeared larger than life and was most often compared to three peculiarly American icons: Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Abraham Lincoln. Literally growing up in a quasi-frontier existence tucked away in a remote Tennessee backwater unscathed by industrialized America, York was born and raised in a log cabin near the Tennessee-Kentucky border–a region which bore no resemblance to the break-neck bustle of New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles–so York seemed to belong to another more idyllic time. As late as 1917, he hunted squirrel, raccoon, quail, wild boar and deer with a muzzle-loader. York’s life caught fire in the American imagination not because of who he was, but what he symbolized: a humble, self-reliant, God-fearing, taciturn patriot who slowly moved to action only when sufficiently provoked and then adamantly refused to capitalize on his fame. Ironically, York also represented a rejection of mechanization and modernization through his dependence upon personal skill. George Pattullo, the Saturday Evening Post reporter who broke the story, focused on the religio-patriotic nature of York’s feat. He titled his piece The Second Elder Gives Battle, referring to York’s status in his home congregation in Pall Mall, Tennessee.

For his actions, York was singled out as the greatest individual soldier of the war and when he returned home in 1919 he was wooed by Hollywood, Broadway, and various advertisers who wanted his endorsement of their products. York turned his back on quick and certain fortune in 1919, and went home to Tennessee to resume peacetime life. Largely unknown to most Americans was the fact that Alvin York returned to America with a single vision. He wanted to provide a practical educational opportunity for the mountain boys and girls of Tennessee. Understanding that to prosper in the modern world an education was necessary, York sought to bring Fentress County into the twentieth century. Thousands of like-minded veterans returned from France with similar sentiments and as a result college enrollments shot up immediately after the war.

The war had introduced York to a mechanized industrial world and his prolonged exposure to it made him realize the important contributions industrialization could make for his friends and relatives at home. Literally a stranger in a strange land, York recognized that he was ill-equipped to fully understand or appreciate his foreign surroundings. Initially he immersed himself in the Bible, hoping that his simplistic religious faith would see him through, but by the war’s end he longed for something more than just his faith.

Yearning to return home and wed his sweetheart, York was taken aback by his New York City hero’s welcome. He prevailed upon Tennessee Congressman and future Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, to facilitate a hasty return to his home. Once back in Tennessee further surprises awaited him. The Rotary Club of Nashville in conjunction with other Tennessee clubs wanted to present York with a home and a farm. Unfortunately not enough money was raised and they gave him an unfinished home and saddled him with a healthy mortgage to boot. As late as 1922, the deed remained in the hands of the Nashville Rotary Club.

Throughout the 1920s York went on speaking tours to endorse his hopes for education and raise money for York Institute. He also became interested in state and national politics. A Democrat in a staunchly Republican county, York’s endorsement carried a degree of clout for pols. York used his celebrity to improve roads, employment, and education in his home county.

York receded from the national spotlight during the 1930s, and focused his waning political aspirations on the state rather than the local level. He considered running for the U.S. Senate against the freshman senator, Albert Gore. In the 1932 election, he changed his party affiliation and supported Herbert Hoover over Franklin D. Roosevelt because FDR promised to repeal Prohibition. Once the New Deal got underway, however, York returned to the Democratic party and endorsed the president’s relief efforts, especially the C.C.C. and the W.P.A. In 1939, York was appointed superintendent of the Cumberland Homesteads near Crossville.

In 1935 York delivered a sermon entitled, Christian Cure for Strife, which argued that the vigilant Christian should ignore current world events, because Europe stood poised on the brink of another war and Americans should avoid it at all costs. Recalling his career as a soldier, York renounced America’s involvement in World War I. In order to achieve world peace, Americans must first secure it at home beginning with their own families. The church and the home, therefore, represented the cornerstones of world peace.

At the same time, the threat of war had rekindled the interest of some filmmakers, most notably Jesse L. Lasky, into reviving the story of York’s exploits during World War I. Lasky, having witnessed the famous New York reception of the hero from his eighth floor office window in May of 1919 had wanted then to tell York’s story. While several other studios found interest in York’s saga in 1919, only Jesse Lasky of Famous Players Paramount (later associated with Twentieth Century-Fox, and finally Warner Brothers) had persistently pursued him. In the late 1930s the world once again appeared on the verge of war and the official stance of the United States government was reminiscent of York’s initial attitude toward the first World War. America (in 1939) and York (in 1917) both had to be convinced that war was not only justifiable, but sometimes necessary.

When York at last relented, he announced that the film would “be a true picture of my life…my contributions since the war. It won’t be a war picture. I don’t like war pictures.” Yet the film that bears his name definitely was a war picture. The original screenplay presented the war as an epiphany for York which forced him to recognize his own inadequacies but fulfilled his wish to improve himself and his homeland. The motion picture that arrived in movie theatres in July of 1941 not only signaled a profound change in York’s pacifism but sounded the clarion for American involvement in World War II.

York’s heartfelt belief that war represented moral evil never wavered before his association with Lasky and the Warner Brothers. In 1937, York not only condemned war but also questioned America’s involvement in the First World War. In that same year, York joined the Emergency Peace Campaign which lobbied against any U.S. involvement in the growing tensions in Europe. A pious peaceful man, York had fought his country’s enemy only after great deliberation and had to be convinced that war was sometimes necessary. His personal struggle in World War I found new resonance in an America at odds over the recent European war, for York personified isolationist Christian America wrestling with its conscience over whether or not to engage in the current war abroad.

Because the Church of Christ in Christian Union condemned movies as sinful, Lasky had a tough time convincing York that a film based on his life was justified. York finally agreed when he decided that the money made from the film could be used to create an interdenominational Bible school. As the film progressed the focus of the project changed and York’s war exploit gained prominence. Through York’s association with Lasky and Warner Brothers, he became convinced that Hitler represented the personification of evil in the world and turned belligerent. York’s conversion to interventionism was so complete that he wholeheartedly agreed with General George C. Marshall that the U.S. should institute its first peacetime draft. Governor Prentice Cooper approved York’s endorsement by naming him chief executive of the Fentress County Draft Board, and appointed him to the Tennessee Preparedness Committee to help prepare for wartime.

In 1940-41, York joined the Fight for Freedom Committee which combated the isolationist stance of America First, and York became one of its most vocal members. Up until Pearl Harbor, York battled another legendary American hero, the man who symbolized America First to the general public, Charles Lindbergh. Meantime, the film Sergeant York starring Gary Cooper, became one of the top grossing Warner Brothers films of the entire war era and earned Cooper the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1942.

During the war, York attempted to reenlist in the infantry but could not do so due to age and obesity. Instead, through an affiliation with the Signal Corps, York traveled the country on bond tours, recruitment drives, and camp inspections. Ironically, the Bible school that was built with the proceeds from the movie opened in 1942, but the very people the school was intended for had either enlisted in the armed services or moved north to work in defense related industries. The school closed in 1943 never to reopen.

York’s health began to deteriorate after the war and in 1954 he suffered from a stroke that would leave him bedridden for the remainder of his life. In 1951, the Internal Revenue Service accused York of tax evasion regarding profits earned from the movie. Unfortunately, York was practically destitute in 1951. He spent the next ten years wrangling with the IRS, which led Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and Congressman Joe L. Evins to establish the York Relief Fund to help cancel the debt. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy ordered that the matter be resolved and considered the IRS’s actions in the case to be a national disgrace. The relief fund paid the IRS $100,000 and placed $30,000 in trust to be used in the family’s best interest.

York died on September 2, 1964 and was buried with full military honors in the Pall Mall cemetery. His funeral was attended by Governor Frank G. Clement and General Matthew Ridgway as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s official representative. He was survived by seven children and his widow.

When asked how he wanted to be remembered, the old sergeant said he wanted people to remember how he tried to improve basic education in Tennessee because he considered a solid education the true key to success. It saddened him somewhat that only one of his children went on to college, but he was proud of the fact that they all had received high school diplomas from York Institute. Most people, of course, do not remember him as a proponent for public education. York’s memory is forever tied to Gary Cooper’s laconic screen portrayal of the mountain hero and the myth surrounding his military exploits in the Argonne in 1918.

Alvin York kept an excellent diary of his war service which can be accessed at:

http://www.worldwar1.com/dbc/biograph.htm

Michael E. Birdwell, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of History at Tennessee Technological University and Archivist of Alvin C. York’s papers.