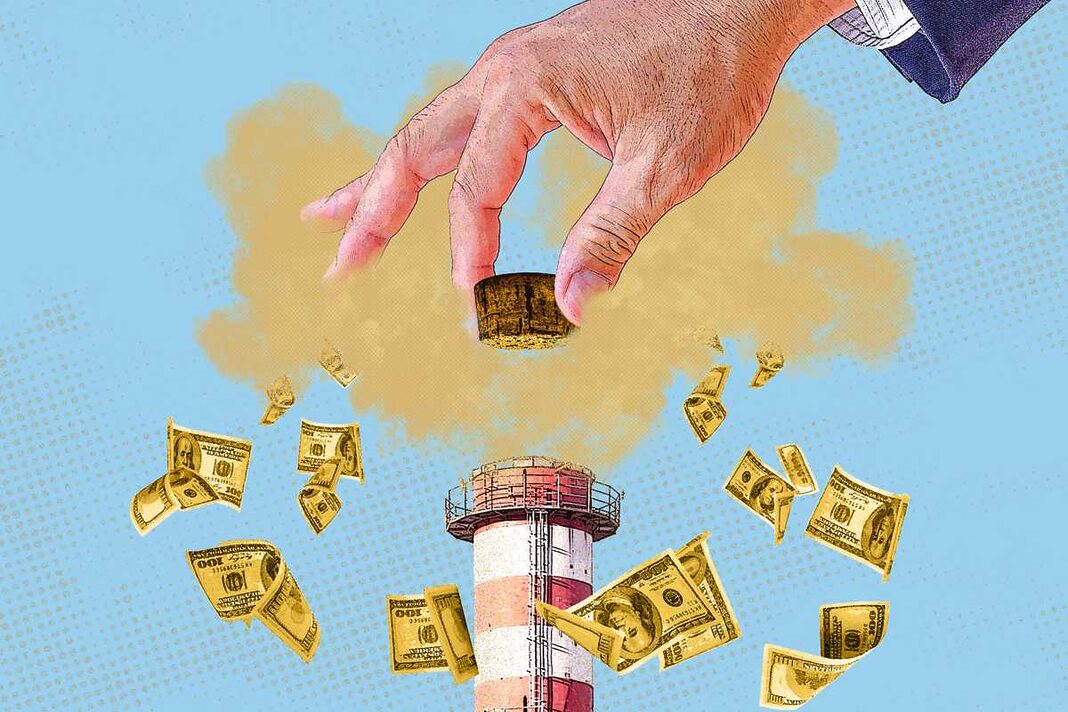

Opponents say it’s a regressive tax that doesn’t deliver anything, while proponents say it’s not a tax, but it puts a price on greenhouse gas emissions.

The United States is following Europe’s lead in instituting cap-and-trade regimes to reduce CO2 emissions, but America’s journey is split between two paths—Democrat-run states that have passed cap-and-trade mandates, and Republican-run states that appear to have no intention of doing so.

In the middle are several swing states that have entered, then exited, cap-and-trade pacts, depending on which party gains the upper hand.

As global demand for oil, gas, and coal hits record levels and shows no signs of slowing, cap-and-trade has been hailed as an alternative way to reduce the use of fossil fuels by setting caps on how much CO2 companies can emit, and then allowing those that exceed the cap to purchase credits from companies that emit less, or to invest in projects, such as preserving forests, that purport to offset emissions.

The financial currency of the cap-and-trade market is called an “allowance,” which gives companies the right to emit greenhouse gasses. Each allowance is valued in terms of tons of emitted CO2, currently priced at less than $10 per ton, though organizations such as the World Bank have said that pricing in the range of $50–$100 per ton is needed to meet the net-zero goals of the Paris Climate Accords.

Advocates of cap-and-trade hail it as a “market-based” solution.

“Cap and trade harnesses the power of the market to fight global warming,” a report by the Environmental Defense Fund states.

“The cap on emissions guarantees the environmental results we need,” the report states. “Trading gets it done in the cheapest way possible.”

But some critics are skeptical, arguing that it is essentially a tax on energy that gets passed on to consumers and commuters, and that insiders may benefit more than the environment from the enormous sums of cash paid into the system.

“Cap-and-trade is a very interesting theoretical model to try to solve a policy problem, but it’s one that ultimately ends up just moving the costs around,” Ryan Yonk, an energy economist at the American Institute for Economic Research, told The Epoch Times.