The court’s ruling could deal a blow to the abortion provider or widespread efforts to strip its government funding.

The U.S. Supreme Court may have turned the page on its previous role in ruling on national abortion policy, but it appears that the justices will still have a prominent part to play in the next chapter.

On April 2, the court will hear a case that does not directly affect abortion law but could have significant implications for the nation’s largest abortion provider.

At the heart of the case is the question of whether federal law unambiguously bestows Medicaid patients with the right to choose a specific provider. Planned Parenthood and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals say it does.

But the state of South Carolina, which bars taxpayer funding of abortion, says the law empowers states to decide which providers are qualified for Medicaid funding. South Carolina has asked the Supreme Court to step in.

Depending on how it’s decided, the case could deal a potentially fatal blow to Planned Parenthood or set back widespread efforts to defund the organization once and for all.

The Case

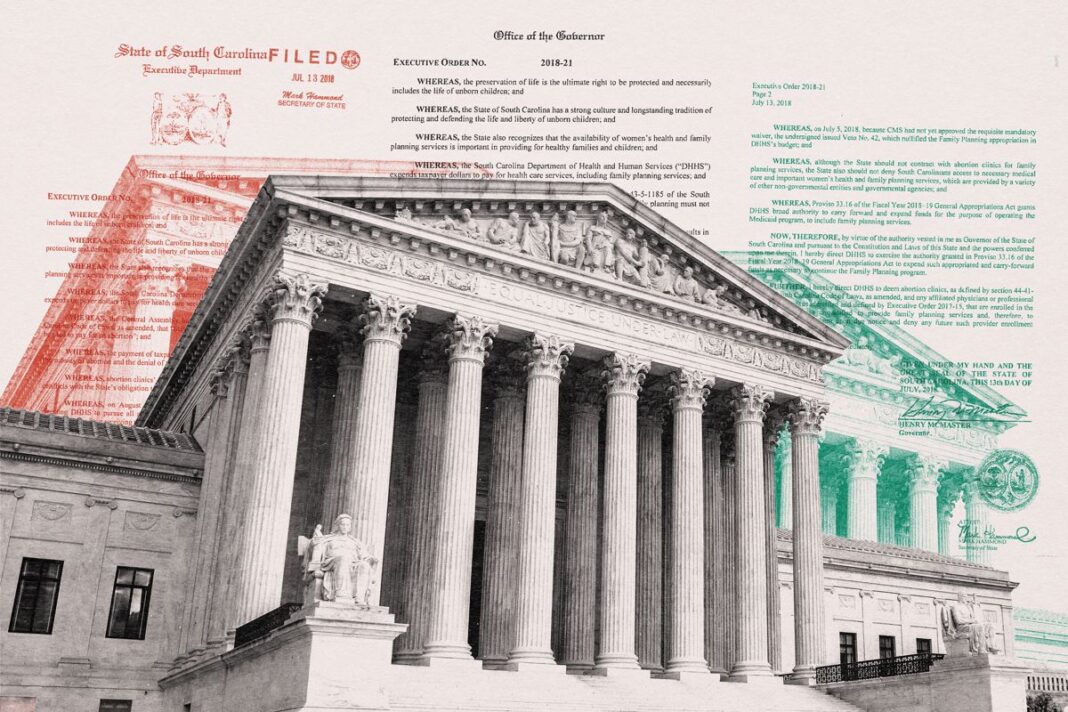

The case was prompted by South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster’s 2018 directive ordering the state’s health department to terminate all abortion providers from the Medicaid program. The order deemed all abortion clinics to be “unqualified” to provide family planning services.

Planned Parenthood South Atlantic and one of the affiliate’s Medicaid patients swiftly filed a federal lawsuit challenging the order.

At issue is a provision of the Social Security Amendments of 1965, also called the Medicare and Medicaid Act. The statute requires state Medicaid plans to “provide that any individual eligible for medical assistance … may obtain such assistance from any [provider] qualified to perform the service or services required … who undertakes to provide him such services.”

Planned Parenthood holds that verbiage grants Medicaid beneficiaries the right to receive care from the qualified and willing provider of their choice.

The district and appeals courts both agreed, finding that the law “unambiguously [creates] a right privately enforceable” under a civil rights statute.