Drawing on research from a multimillion-dollar Mark Zuckerberg-linked initiative viewed as pivotal in the 2020 presidential election, 14 states carried by Joe Biden have appealed to him for billions of dollars more to secure elections for the next decade. But most of them have spent less than half their shares of previous federal funding to counter alleged Russian election meddling and other “threats” to election security.

The states’ letter to the president cites a report by the Election Infrastructure Initiative, a progressive nonprofit that estimates $53 billion in taxpayer money will be needed to ensure election security over the next decade.

The Election Infrastructure Initiative is an arm of the Center for Tech and Civic Life, which in 2020 distributed nearly $400 million in private grants—$350 million from Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan—to local election offices in 48 states and the District of Columbia for the pandemic-challenged presidential election.

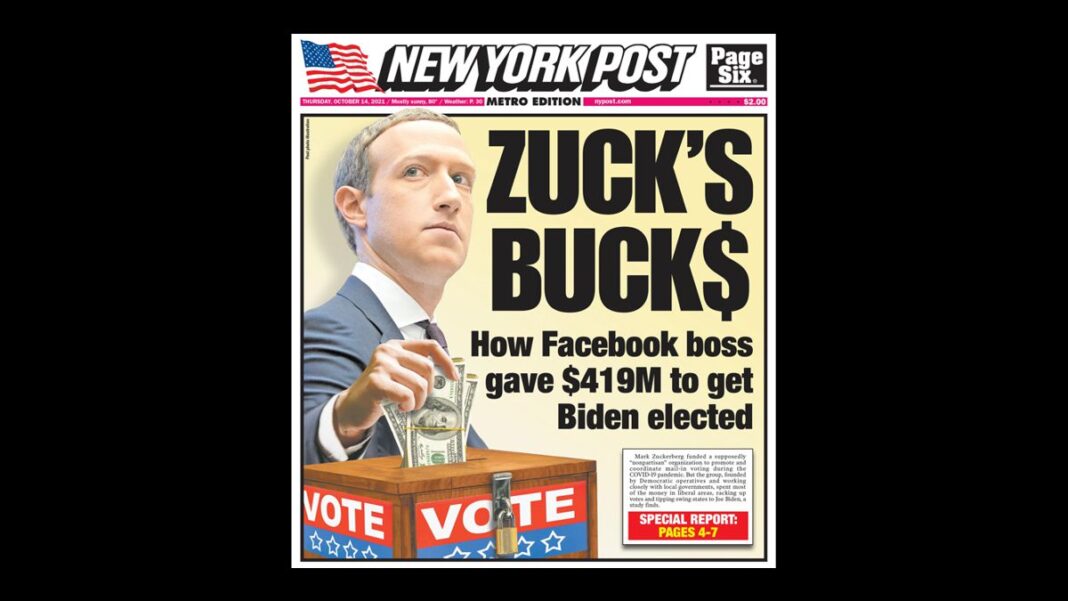

Some conservative analysts contend the money, dubbed “Zuck Bucks,” was strategic in its placement, beefing up vote totals for Biden in swing states and allowing him to win the election—a view that found support in a Time magazine cover story on the effort. Tiana Epps-Johnson, executive director of the Center for Tech and Civic Life, did not respond to an interview request.

The 14 states seek $20 billion in federal money over the next 10 years. (Theirs is not a national estimate, unlike the Zuckerberg-linked group’s). It would pay for election administration, including security, personnel, “and other essential needs.”

While no money has yet been allocated, federal funding remains a key part of Democrat-backed “voting rights” measures that would set new voting standards for federal elections. But sitting in state coffers are hundreds of millions of dollars still left from two funding rounds of $380 million (2018) and $425 million (2020) under the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA).

Colorado, for example, has spent 15 percent of its security grant money, according to the most recent report from the Elections Assistance Commission, the federal agency that oversees HAVA grant spending. Vermont has spent 27 percent of its funding, and Minnesota 13 percent. All three states are among those appealing to Biden for more money—as are swing states Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Michigan along with deep-blue states such as California, and New York.

Collectively, states still have 48 percent of the $805 million in HAVA security funding doled out over the past four years, or $383 million.

Democrats are not alone. While the Biden administration’s plan to federalize national elections has so far been thwarted in Congress, a growing number of Republicans are joining Democrats in calling for more federal money for elections—albeit insisting on retaining state autonomy.

Last month, a group of think tanks including the conservative American Enterprise Institute issued a proposal that would allow states to voluntarily accept federal money for election needs. Republicans oppose as a ”federal takeover” of elections Democratic measures like the recently defeated Freedom to Vote Act, which sought to impose uniform rules on states for federal elections while providing federal funding. Democrats contend the measure would make ballot access easier and voting more secure.

It’s not exactly clear why the 14 states and the Zuckerberg group believe an exponential increase in federal funding is required for elections in coming years when the money previously allocated proved more than sufficient in the past—and with the pandemic receding.

RealClearInvestigations emailed interview requests to the 14 secretaries of state and election chiefs who signed the letter to the administration seeking the $20 billion. Thirteen did not respond. Michigan, the lone respondent, declined to make Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson available. It asked for emailed questions, then declined to answer them.

The Brennan Center, which advocates on behalf of progressives in election issues including increased election funding, did not respond to an interview query. Elections are traditionally funded with a combination of local and state money, and budgets fluctuate, depending on factors such as the number of elections each year, recount costs, and equipment needs.

Several states and counties have boosted their election funding by double-digit percentages over the past five years.

“We don’t know how much elections cost in this country because of how decentralized it is,” said Matthew Weil, director of the Elections Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center, one of the groups that developed the report.

He acknowledged that bureaucratic inefficiency hinders the ability of funding to reach the municipalities that run elections. “Just because a state has money doesn’t mean it’s getting to the locals,” he said.

In 2018, EAC Commissioner Christy McCormick projected in congressional testimony—incorrectly, as it turns out—that states would spend $324 million of the $380 million of 2018 HAVA grant money alone in advance of the 2020 presidential election.

States in 2020 were allowed to use HAVA security grants on pandemic-related election expenses, although states are now returning unused personal protection equipment to the federal government. States were also given $400 million to help run elections in 2020 under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, also known as the CARES Act, a $2.2 trillion economic stimulus bill.

A spokeswoman at the National Association of State Election Directors declined a request for an interview on the unspent money, but in an email said it could have been “allocated to contracts that pay out over a period of years. In other cases, states keep funds in reserve, accruing interest, to make sure they can afford expenses that come up in the future. “

The HAVA grants have no expiration, said Election Assistance Commission chairman Don Palmer, a Trump appointee. He echoed the supposition that some states hold on to the money for future expenses. In the past, Congress has put deadlines on the spending of HAVA grants, he said. But in the case of the most recent security grants, it has not, which is “something unique.”

“I don’t believe these states are hoarding that money,” Palmer said. State legislatures were required to approve some matching funding for the grants—5 percent for the 2018 money and 20 percent for the 2020—which could be holding up the spending in some cases.

In other cases, he said, states may have plans for system upgrades or equipment purchases that are still being worked out. Some states outline the use of their funding in biannual reports. The spending includes voter roll upgrades, security, new hires, polling place accessibility, and messaging.

Among the places with large increases in election funding in recent years are New Mexico, where the budget jumped 73 percent between 2013 and last year. In Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston, commissioners increased the election budget by $17.1 million to $27 million in 2020 after spending $4 million in 2016.

Elections have evolved in the past 20 years, said Julie Leathers Stahl, who is director of the board of elections in Wayne County, Ohio. Stahl, a Republican, signed a letter to Congress in June along with 250 other elections administrators and local and state elected officials from around the United States asking for federal elections money.

Stahl said that she doesn’t need any funding at this point, nor has her office encountered any threats to its elections. She still sounds as though she wouldn’t turn it down. “We’ve got to have the funding to keep up with technology and bad actors,” she said. “Can’t everybody use more money?”

Since 2002, the Election Assistance Commission has made periodic grants for system upgrades and other necessities under HAVA, the law Congress passed in the wake of the 2000 presidential election, when ballot-counting snafus in Florida led to an outcome that had to be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

As the move toward regular federal election grants gains momentum—including the conservative proposal backed by the American Enterprise Institute—the EAC is increasing its own ranks as bureaucrats ask for more federal involvement in elections. In 2021, the agency added 11 full-time staffers, a personnel increase of 26 percent. Its budget was hiked to $17 million, up 84 percent from 2019’s $9.2 million, and the highest since 2010’s $17.9 million budget.

Between 2010 and 2018, there were no HAVA grants issued, and election disputes were typically limited to local problems, mostly related to mail-in balloting, and ineligible voting.

“With the debate over election security, though, there was a renewed sense that we needed to help the states,” Palmer, the EAC chairman, said.

Greater adoption of federal funding for elections poses the same mixed blessing of cash with conditions that has long applied to road allocations, education, law enforcement, and other federal largesse.

“If you continue to pump federal money into elections, the feds will eventually start trying to tell you how to run things,” said Doug Lewis, former executive director of the Elections Center, also known as the National Association of Election Officials. “That means whatever party is in control gets to control the process. “

By Steve Miller