How is it that politicians often enter office with relatively modest assets, but then, as investors, regularly beat the stock market and sometimes beat the most rapacious hedge funds? How did some members of Congress know to dump their stock holdings just in time to escape the effects of the 2008 financial meltdown? And how is it that billionaires and hedge fund managers often make well-timed investment decisions that anticipate events in Washington?

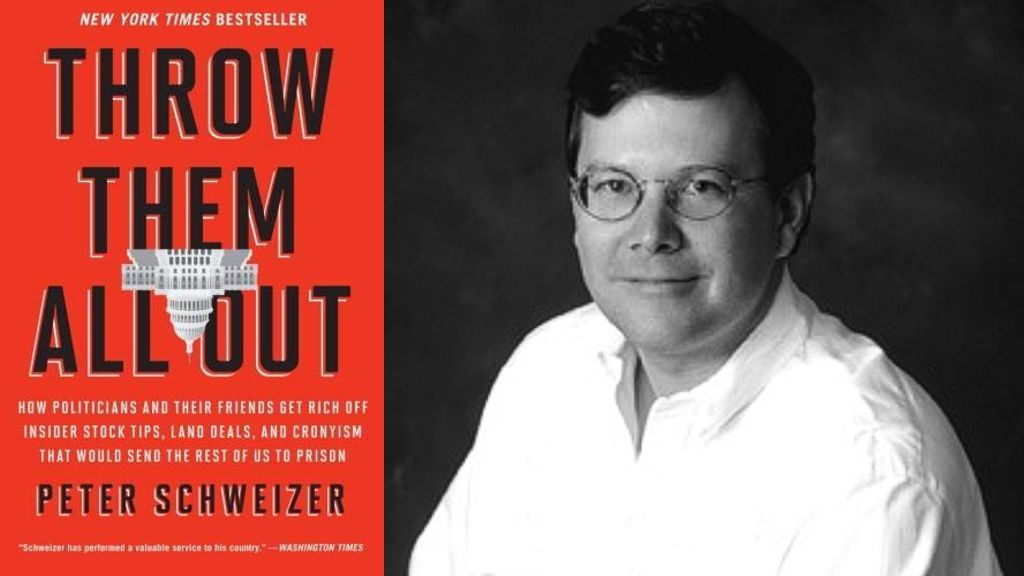

In this powerfully argued book, Throw Them All Out, Peter Schweizer blows the lid off Washington’s epidemic of “honest graft.” He exposes a secret world where members of Congress insert earmarks into bills to improve their own real-estate holdings, and campaign contributors receive billions in federal grants. Nobody goes to jail. Throw Them All Out casts light into the darkest corners of the political system — and offers ways to clean house.

“Throw Them All Out is filled with stories of petty theft and so-called ‘honest graft’ . . . Unsparingly bipartisan in [its] criticism of Washington . . . Mr. Schweizer has performed a valuable service to his country.” — Washington Times

From the Back Cover

THE BOOK WASHINGTON DOES NOT WANT YOU TO READ

How is it that politicians often enter office with relatively modest assets, but then, as investors, regularly beat the stock market and sometimes beat the most rapacious hedge funds? How did some members of Congress know to dump their stock holdings just in time to escape the effects of the 2008 financial meltdown? And how is it that billionaires and hedge fund managers often make well-timed investment decisions that anticipate events in Washington?

In this powerfully argued book, Peter Schweizer blows the lid off Washington’s epidemic of “honest graft.” He exposes a secret world where members of Congress insert earmarks into bills to improve their own real-estate holdings, and campaign contributors receive billions in federal grants. Nobody goes to jail. Throw Them All Out casts light into the darkest corners of the political system and offers ways to clean house.

“Throw Them All Out is filled with stories of petty theft and so-called ‘honest graft’ . . . Unsparingly bipartisan in [its] criticism of Washington . . . Mr. Schweizer has performed a valuable service to his country.” —Washington Times

PETER SCHWEIZER is the William J. Casey Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He is also president of the Government Accountability Institute, an organization he launched to research and investigate crony capitalism. His books have been translated into eleven languages and include Do As I Say (Not As I Do), Reagan’s War, and Architects of Ruin. He lives in Florida with his wife and children.

About the Author

Peter Schweizer was formerly the William J. Casey Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Newsweek/Daily Beast, and elsewhere. He is the cofounder and president of the Government Accountability Institute, a team of investigative researchers and journalists committed to exposing crony capitalism, misuse of taxpayer monies, and other governmental corruption or malfeasance. He lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

Peter is the author of, among other books, Clinton Cash, Extortion, Throw Them All Out, and Architects of Ruin and Secret Empires: How the American Political Class Hides Corruption and Enriches Family and Friends. He has been featured throughout the media, including on “60 Minutes” and in the “New York Times.”

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The Government Rich

The mere proposal to set the politician to watch the capitalist has been disturbed by the rather disconcerting discovery that they are both the same man. We are past the point where being a capitalist is the only way of becoming a politician, and we are dangerously near the point where being a politician is much the quickest way of becoming a capitalist. —G. K. CHESTERTON

Just follow the money. —“DEEP THROAT” TO BOB WOODWARD

We’ve all heard about the New Rich. Once, they were the Oil Rich. Then they were the Silicon Valley Rich. The Dot-Com Rich. Now it’s time to meet the New New Rich: the Government Rich.

For the Government Rich, insider deals, insider trading, and taxpayer money have become a pathway to wealth. They get to walk this exclusive pathway because they get to operate by a different set of rules from the rest of us. And they get to do this while they are working for us, in the name of the “public service.”

This is not another book about socioeconomic issues, campaign finance, or political action committees. And it’s not about the kind of corrupt politicians who stuff money in their freezers. If anything, corrupt politicians of that sort are vintage stuff now. Dishonest graft is quaint. This is a book about how a Permanent Political Class, composed of politicians and their friends, engages in honest graft. Let’s call it crony capitalism. Here the “invisible hand” is often attached to the long arm of Washington. And business is good.

Consider just one example: Dennis Hastert was a jovial ex– high school wrestling coach and member of the Illinois House of Representatives when he was first elected to Congress in 1986. Through hard work, attention to detail, and a knack for coalition building, he rose to be Speaker of the House in 1999 and served until 2007, when he resigned. When Hastert first went to Congress he was a man of relatively modest means. He had a 104-acre farm in Shipman, Illinois, worth between $50,000 and $100,000. His other assets amounted to no more than $170,000. He remained at a similar level until he became Speaker of the House.1 But by the time he set down the Speaker’s gavel, he was substantially better off than when he entered office, with a reported net worth of up to $11 million.

Washington today is full of politicians like Hastert. They have unprecedented opportunities, rich friends, and tight webs of influence. The famous sociologist Max Weber once gave a lecture where he discussed “politics as a calling.” He talked about people who would live for politics. But he also pointed out that some people would live from it.2

“Either one lives ‘for’ politics or one lives ‘off’ politics . . . He who strives to make politics a permanent source of income lives ‘off’ politics as a vocation.” Today some people are living very well thanks to crony capitalism in Washington.

Politicians have made politics a business. They are increasingly entrepreneurs who use their power, access, and privileged information to generate wealth. And at the same time well-connected financiers and corporate leaders have made a business of politics. They meet together in the nation’s capital to form a political

caste.

How is it that politicians manage to enter office with relatively meager resources and often retire rich? It’s certainly not by clipping coupons or a hefty paycheck. Politicians learned long ago that they could not pay themselves extravagant salaries. People would simply not tolerate it. Back in the spring of 1816, Congress passed a compensation bill that roughly doubled its members’ pay. The result? A populist revolt. John Randolph of Roanoke, a Virginia congressman, likened the public’s reaction to “the great Leviathan rousing into action.” There was universal outrage. As a result, more than half the members of the House of Representatives declined to stand for reelection, and only 15 of the 81 who voted for the raise and who did run for reelection managed to keep their seats. Three states—Ohio, Delaware, and Vermont—elected entirely new congressional delegations. Henry Clay managed to retain his seat only after apologizing for voting in favor of the bill and promising he would never do such a thing again. When the new Congress sat, it quickly repealed the act.3

Ever since 1816 a large pay raise has been out of the question. In 2011, rank-and-file members of the House and Senate earned salaries of $175,000.4

If you include their benefits, the pay is more like $285,000 a year, which means they made approximately 3.4 times more than the average full-time worker in America, and twice what private sector workers with master’s degrees earn. That salary makes them the second-highest-paid legislators in the world—Japan is number one. (Luckily for our legislators, their contracts don’t include pay based on performance standards.)5

It’s a respectable paycheck, but hardly the kind of money that leads to millions of dollars in savings, especially for men and women who maintain a Washington residence in addition to a house or apartment in their home state.

For many, serving in Congress is the best job they will ever get. Besides the income, they are rewarded with power and responsibility. But increasingly, members are leveraging that power and responsibility to create wealth, too.

Crony capitalism unites these politicians with a certain class of businessmen who act as political entrepreneurs. They make their money from government subsidies, guaranteed loans, grants, and set-asides. They seek to steer the ship of state into profitable seas. Twenty-first-century privateers, they pursue wealth through political pull rather than by producing new products or services. In addition to these political entrepreneurs, big investors turn to lobbying and insider information from their sponsored politicians to make their investment decisions. And business is very good.

Political contacts, inside information, financial connections, and influence are increasingly replacing open competition. Hard work and innovation should be driving the American economy, but in Washington, crony connections have thrown these stable economic helmsmen overboard. Under crony capitalism, access to government officials who can dole out grants, special tax breaks, and subsidies is an alternative path to wealth.

So how does it work?

In his novel The Reivers, William Faulkner describes an entrepreneurial scoundrel who uses his mules and plow to make a boggy road even less passable. When the main character’s car inevitably gets stuck there, the scoundrel shows up with a mule and offers to pull the car out—for two dollars, a hefty price in 1905. Shift the scene to Washington, and this form of extortion becomes a much bigger profit opportunity. And it’s the political class that muddies the road before charging to pull us out.

The new crony capitalists use several kinds of mud. They obtain access to initial public offerings on the stock market that can often be lucrative. They make their investment decisions and trade stock based on what is happening behind closed doors in Washington. This might entail buying or selling stock based on what they know to be going on, or they might “prime the pump,” trading stocks based on legislation they have introduced.

Politicians are often extraordinarily good investors—too good to be true. They may not have figured out how to help our economy prosper, but the Permanent Political Class is itself prosperous to a degree that should make us all suspicious. One study used a statistical estimator to determine that members of Congress were “accumulating wealth about 50% faster than expected” compared with other Americans.6

According to the Center for Responsive Politics in Washington, members saw their net worth soar, on average, an astonishing 84% between 2004 and 2006.7

(Other Americans didn’t do quite so well, averaging about a 20% jump in the same period.)8

And when times turned lean, in 2009, with the rest of the country mired in recession, members of Congress nonetheless saw their net worth increase by 6%, while the average American’s net worth plunged by 22%.9

Reuters even ran a story on the subject, titled “Get Elected to Congress and Get Rich.”10

A study in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis found that U.S. senators may have missed their calling: they should all be running hedge funds. How else to explain these results, based on 4,000 stock trades by senators:

• The average American investor underperforms the market.

• The average corporate insider, trading his own company’s stock, beats the market by 7% a year.

• The average hedge fund beats the market by between 7% and 8% a year.

• The average senator beats the market by 12% a year.11

When the same team looked at 16,000 trades by members of the House of Representatives, they found similar if less spectacular results. House members beat the market by 6% a year, almost as much as what corporate insiders achieve when trading their own stock.12 (It is unclear why senators are better investors than are representatives. Perhaps it is because they have relatively more power and therefore greater access to market-moving information.)

Another study, by scholars at MIT and Yale, looked at a shorter period of time, from 2004 to 2008, and found that while many individual legislators do not beat the market, they do extremely well with stock in companies with which they are “politically connected.” They beat the market by almost 5% a year. As the researchers put it, “Members of Congress seem to benefit as investors from knowledge of companies to which they are politically connected (and particularly those headquartered in their districts), and they appear to take advantage of this knowledge by investing disproportionately in those companies.”13

“They seem to know something that other people don’t know,” said Jens Hainmueller, coauthor of the study and an assistant professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.14

The winners are the politicians who possess insider knowledge, or who are most likely to receive favors from wealthy supplicants.

That’s one side of the crony-capitalist spider web. On the other side are the political entrepreneurs and private investors. There is disturbing evidence that politically connected hedge funds perform dramatically better than those without Washington contacts. One study found that politically connected hedge funds beat their equivalent nonpolitical counterparts by about 2% per month.15

In short, the Permanent Political Class has clearly figured out how to extract wealth from the rest of us based solely on their position and proximity to power. If you have a seat at the table, you are in for a feast. If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu. Exactly how crony capitalists are consuming public wealth and fattening themselves is the subject of this book.

Ideology and political philosophy matter in Washington, but often less than you might think. Honest graft is generally bipartisan. Complex bills that are hundreds or even thousands of pages long can contain a single sentence or word that translates into money and that can influence how a politician votes. One study by scholars at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business and the University of Chicago found that during the critical votes on the subprime-mortgage bailout and subsequent matters related to the financial crisis of 2008, a key factor in how members of Congress voted was whether they held stock in banks and in the financial sector. Personal equity ownership also influenced congressional committee decisions on the amount of bailout money particular financial institutions received and how quickly they got it. Apparently the vote had less to do with your politics and more to do with your pocketbook.16

Is it any surprise that Washington lawmakers are staying in office longer than they did before, and that in recent years we’ve had the oldest Congress ever?17 Long gone are the days when Thomas Jefferson could write, as he did in 1807 to Count Jules Diodati, “I have the consolation of having added nothing to my private fortune during my public service, and of retiring with hands as clean as they are empty.”18 Now, politicians’ fortunes are rising, and they are clinging to their jobs for all they’re worth.

But hasn’t it always been this way? Graft has a long and sordid history in America. In 1789, Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. secretary of the Treasury, announced plans to pay off both the federal Revolutionary War debt and the debt obligations of the individual states, all at 100%. The deal was preceded by massive insider trading in federal and state government bonds. Members of Congress were among the speculators who traded these bonds, based on advance knowledge of the Treasury’s intent. According to Senator William Maclay, Democrat of Pennsylvania, speculators sent people in stagecoaches all over the country to buy up federal and state notes at a fraction of their face value.19

Crony capitalism is not new, but it has become a dominant force in Washington. The amount of money to be made is much larger. And the opportunities have become more frequent. In fact, it is now threatening the health and integrity of our entire economic system. “Crony capitalism” is a term that used to be applied almost exclusively to developing countries that were rife with corruption. Now the label can be applied to many sectors of our economy. It is an important part of the reason we face the economic crisis that we do.

One of the best-known chroniclers of crony capitalism in the nineteenth century was one of its participants. George Washington Plunkitt was a party boss of the infamous Tammany Hall, the corrupt political machine that ruled New York City for decades. Plunkitt was born in poverty, in a squatter’s hut in what is now Central Park. He left school at the age of eleven and became a multimillionaire through elective office. He explained quite candidly in a series of newspaper interviews in the 1870s how he did it.

Plunkitt’s philosophy was that politics is a business. How did he begin his career? “Did I get a book on municipal government . . . ? I wasn’t such a fool. What I did was get some marketable goods. What do I mean by marketable goods? Let me tell you: I had a cousin. I went to him and said, ‘Tommy, I’m goin’ to be a politician, and I want a followin’, can I count on you?’ He said, ‘Sure, George.’ That’s how I started in business. I got a marketable commodity—one vote.”20

Plunkitt continued with the classic description that has kept his name alive long after his death:

“There is a distinction between honest graft and dishonest graft. I’ve made a big fortune out of the game, and I’m getting richer every day, but I’ve not gone in for dishonest graft—blackmailing gamblers, saloonkeepers, disorderly people, etc.—and neither has any of the men who have made big fortunes in politics. There’s an honest graft, and I’m an example of how it works. I might sum up the whole thing by saying: ‘I seen opportunities and I took ’em.’ ”

He goes on: “Just let me explain by examples. My party’s in power in the city, and it’s going to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. Then the board of this or that makes its plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before. Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft.”21

More recently, Lyndon Johnson, while he served in the House and the Senate, told people to purchase advertising on his Austin radio station, KBTC, in order to get his attention.22 LBJ also frequently used his power at the Federal Communication Commission to obtain licenses for his radio and television stations and to block competitors from invading his markets in Texas. His company, needless to say, prospered. An initial investment of $17,500 grew into a media empire worth millions.23

Or consider the case of the late Congressman Tom Lantos of California. He was one of the most respected representatives and a champion of human rights. But no mention has ever been made of the glaring conflict of interest that was central to his personal financial life. A former economics professor at San Francisco State University, he served in the House for more than twenty-five years. Through much of his later public life, Lantos invested heavily in the stock of a single company. He never worked for the company. Indeed, the company was not even in his district.

When he first went to Congress, Lantos had little in the way of Boeing shares. But he kept buying and buying, year after year. According to his last financial disclosures, Lantos ended up owning between $1 million and $5 million of stock in the airplane maker. This when his total net worth was between $1.9 and $11 million.24

Lantos did very well with his investment. When he first arrived in Congress, Boeing stock was trading at $5 a share. By the time he died in 2008, it was $85 a share. It’s hard not to come to the conclusion that Lantos had something to do with Boeing’s success.

So why did Lantos tie up so much of his wealth in the fortunes of one company? It probably had something to do with the fact that because of his congressional position, he had an extraordinary amount of influence over the health of Boeing. Lantos served as chairman and ranking member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, which had direct oversight of the Export-

Import Bank, a little-known federal agency that operates as one of the most blatant examples of corporate welfare in America. (Both the libertarian Cato Institute and Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-professed socialist, have denounced the Export-Import Bank as “corporate welfare at its worst.”) Created at the height of the Great Depression, the bank had the goal of boosting American manufacturing.

Today, the Ex-Im Bank is often referred to as “Boeing’s bank.” The bank helped fund more than 25% of the airliners Boeing delivered in 2009, for example. In 2008, the year Lantos died, Boeing deals accounted for almost 40% of the bank’s $21 billion in business. Boeing is a major manufacturer in the United States, to be sure, but the amount of support it receives is totally out of proportion to its size. The recent Ex-Im investments are actually down from their height. In 1999, 75% of the Export-Import Bank’s financing went to Boeing. That same year, shareholders like Lantos saw the stock price jump from $32 to $45 a share.25

About 2% of all U.S. exports get Ex-Im financing; about 20% of Boeing’s business does. In other words, it’s ten times more likely to get funds than are other exporters.26 As the Wall Street Journal put it, “No company has deeper relations with Ex-Im Bank than Chicago-based Boeing.”27

Lantos was a champion of Ex-Im, fighting off efforts by conservative Republicans to end it and aggressively pushing for its reauthorization. He was a tireless advocate of a government program that was directly benefiting his largest single stock asset.

Honest graft is so insidious because it piggybacks on legitimate service, and cloaks both in the name of public good.

Give someone the chance to feel that they are serving the public and getting rich at the same time and you have created a nightmare. Always a practical observer of human nature, Benjamin Franklin in 1787 expressed concern to the Constitutional Convention that when you give politicians the opportunity to “do good and do well” you are asking for trouble: “There are two passions which have a powerful influence in the affairs of men. These are ambition and avarice; the love of power and the love of money. Separately, each of these has great force in prompting men to action; but when united in view of the same object, they have in many minds the most violent effects. Place before the eyes of such men a post of honor that shall at the same time be a place of profit, and they will move heaven and earth to obtain it.”

Ben Franklin knew human nature. He would not have been surprised by the deep sense of entitlement claimed by the Government Rich. Because of their “public service” and “sacrifice” to us, they feel entitled to the manipulation of the business market for their own benefit. Their attitude is that the rules that apply to the rest of us—insider trading laws, conflict-of-interest statutes—don’t apply to them and never should. The Permanent Political Class is, and expects to continue to be, untouchable.

The Permanent Political Class does not produce any goods or services. Their ability to make money rises from their ability to extract wealth by leveraging it from others. Politicians can write legislation that can destroy corporations or help them prosper. They can perform constituent services to benefit friends or punish enemies. They can intervene with bureaucrats in a way that can reap billions for a company. They have access to information that can dramatically affect the economy and financial markets, information that few other people have.

All of this crony capitalism comes at a high price for the rest of us. Under free market capitalism, the idea is that a rising tide lifts all boats. Henry Ford wanted Americans to become more prosperous because then he could sell them more cars. Crony capitalism is a zero-sum game. Crony capitalists don’t care whether a rising tide lifts all boats. They just want to buy their way onto the big party boat.

All too often people assume that corporations and special interests have the real power and that politicians are mere corks tossed around in the rough surf of capitalism. The fact is that the Permanent Political Class has immense formal and informal powers that are both blunt and subtle. For example, your chance of getting audited by the Internal Revenue Service often depends on who your congressman is. One study found that the IRS actually shifts enforcement away from congressional districts represented by legislators who sit on committees with oversight of the IRS.28

A study by Stanford University’s Rock Center for Corporate Governance found evidence that firms that make political contributions and hire lobbyists are less likely to face enforcement actions by the Securities and Exchange Commission. And if they are subject to an SEC enforcement action, they are likely “to face lower penalties on average.”29

Two professors found that companies that hire lobbyists are, on average, much less likely to be detected for fraud, or they can evade detection for 117 days longer than average. These firms are also 38% less likely to be detected by regulators. The scholars note that “the delay in detection leads to a greater distortion in resource allocation during fraudulent periods. It also allows managers to sell more of their shares.” Having friends in Washington can be extremely valuable.30

Washington’s financial leveraging power can be found even in something as seemingly innocuous as the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The act can have an enormous economic effect on property owners and developers. Scholars at Auburn University found that the implementation of the ESA has been highly political. Politics determine which species gets listed as threatened or endangered and how quickly (or slowly) a certain species gets recognized and protected. The researchers found that states with House members on the budget oversight subcommittee responsible for funding the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Environmental Protection Agency had significantly fewer listings than other states. As the researchers put it, “Congressional representatives who sit on the Interior subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee use their position to shield their constituents, at least partially, from the adverse consequences of ESA.”31

By looking at Department of Housing and Urban Development grants designed to combat economic blight and help “distressed” cities, researchers found that there was no evidence that these factors had any real effect on how the HUD grants were awarded. The decisions were instead based on political influence, by bureaucrats rewarding friends.32

Has anything really changed since George Washington Plunkitt’s day? The methods, techniques, and tools are similar. But while Tammany Hall corruption controlled a city, today’s crony capitalism is about a system that operates at the highest levels of an entire nation.

There is a lot of money sloshing around in the nation’s capital. As of 2010, seven of the ten richest counties in the United States were in the Washington, D.C., area. During the Great Recession of 2008–2009, Washington boasted the best-performing real estate market in the country. What is it that drives the D.C. economy? Not private enterprise, certainly. And we can only expect these trends to continue, unless we make changes.33

The upper tiers of the U.S. economy are increasingly a network of individuals who make special deals with politicians—and the politicians themselves. The distinction between the public and private sectors has become blurred. More than half of the Fortune 1000 companies have an ex-politician or ex-bureaucrat sitting on their corporate boards.

Before plunging into the specifics and key offenders of modern crony capitalism, we need to ask: How is this possible, and why does our system of laws allow all this to happen? As you will see, the answer isn’t simply a matter of overlooked corruption. The system of crony capitalism has powerful defenders.

The bank robber Willie Sutton was once asked why he robbed banks. His well-known response: “Because that’s where the money is.” Why has crony capitalism become so widespread? The response is the same. Let’s take a look at how the crony insiders get their loot.