Mark Twain once observed, “History never repeats itself, but it rhymes.”

As midterm elections approach, Democrats face challenges eerily similar to those following President Richard Nixon’s 1972 landslide reelection. Their response was a select committee to stage a legislative show trial where they controlled the agenda and disgraced witnesses could be called to account without the inconvenience of due process rights guaranteed by our Constitution.

They appear to be following the same playbook today, half a century later. Times have changed, but Democrats’ willingness to abuse government power to punish political enemies hasn’t. Let’s jump inside their heads for a few moments (if you can bear it) to follow the logic of their plots.

Democrats Circa 1972

We lost the election in a landslide by putting up Sen. George McGovern (D-S.D.), a progressive candidate who favored “Amnesty, Acid, and Abortion” and promised to raise taxes. Nixon won every state except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Fortunately, we maintained our huge congressional margins and should harness them to destroy Nixon and his people. It’s our only chance to turn the tide in our favor.

Our best opportunity stems from skillful exploitation of the Watergate break-in earlier this year. The burglars were caught red-handed, making their convictions a certainty. But these were low-level people and federal trials are not televised, so there’s no real drama there. The key is a public investigation by a congressional committee, where we have full control. By getting actual prosecutions delayed, we’ll be the only game in town. We can rely on our media friends to echo our narrative. One thing’s for sure: the press hates Nixon and will be with us every step of the way.

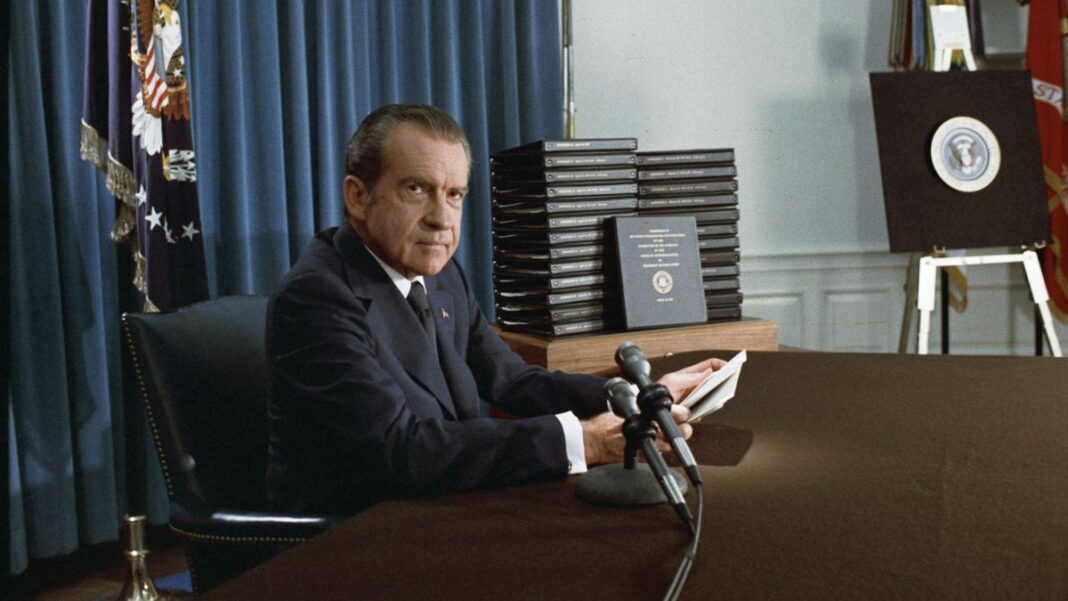

The result is that America’s understanding of Watergate comes from the riveting, nationally televised hearings of the Senate Watergate Committee, popularly known as the Ervin Committee, after its folksy chairman, Sam Ervin of North Carolina.

Democrats Circa 2022

We won a squeaker election in 2020, but that was mainly due to Trump’s combative style and to special circumstances from the pandemic. The tide’s turning against us, and we’re virtually certain to lose our razor-thin congressional majorities in the 2022 midterms. The 2024 outlook isn’t all that rosy, either. America doesn’t seem ready for our progressive policies, including open borders, defunding the police, and appeasement abroad. We have to regain control of the narrative — the sooner, the better.

Our best option is exploiting the January 6 Capitol riot by characterizing it as an armed insurrection, knowingly encouraged by Trump. The challenge is that it’s not at all clear how or why that demonstration got so out of hand — or why law enforcement was so unprepared for that possibility. Let’s use a select committee to launch widespread investigations into every aspect of the Trump presidency, preparatory to staging our own legislative show trial. Let’s also get our Justice Department friends to delay any actual prosecutions, so no adverse evidence or issues of reasonable doubt can surface. As with Watergate, we’ll be the only game in town. And we can count on the mainstream media to echo our narrative of how Trump and his people are responsible for fomenting an armed insurrection.

So how were these situations resolved? Congress has the power to pass laws and to exercise oversight of the executive branch — but not to conduct criminal investigations or to hold “show trials” of political opponents. Yet that’s clearly what has happened. Both select committees see their mission as expanding responsibility for known crimes (the Watergate break-in and the January 6 riot) to the most senior levels of a hated Republican presidency.

Again, the similarities between the two proceedings are striking.

Then: The Ervin Committee

The Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities was created on February 7, 1973, following the convictions of the Watergate burglars. The vote was 77-0, since twenty-three GOP senators abstained rather than join in the political witch hunt. Their abstentions followed party-line votes, giving Democrats a voting majority and limiting the Committee’s investigation to the 1972 presidential election instead of chancing any second look at those from ’60, ’64, and ’68, in which Nixon and Barry Goldwater were on the receiving end of campaign improprieties. The 1976 Church Committee hearings included testimony indicating that Nixon’s campaign was bugged in 1960 and again in 1968 and that the FBI had forwarded derogatory information on Goldwater’s staff to the Johnson White House.

Minority Leader Hugh Scott, an Eastern Establishment Republican from Pennsylvania and no friend of Nixon’s, appointed Howard Baker (R-Tenn.), Edward Gurney (R-Fla.), and Lowell Weicker (R-Ct.) to the Republican minority. Baker, who anticipated a future run for the presidency, concluded it was in his political interest to pose as a nonpartisan truth seeker. Weicker proudly announced his overriding goal was to sink Nixon. Gurney, hardly a hard worker, received critical press whenever appearing to side with Nixon.

The committee staff was equally mismatched. The majority got 75 percent of the funds and most of the personnel. Chief Counsel Sam Dash really ran the operation, helpfully providing questions for each senator to pose in carefully scripted hearings. The result was a consistent anti-Nixon plot line, devoid of any hint of partisan bickering.

Minority Counsel Fred Thompson, while later a movie star and senator in his own right, was a babe in the Washington woods. He’d run Baker’s recent reelection campaign and saw his job as making his senator look good, rather than defending the embattled President. Following Nixon’s resignation, Thompson wrote a book — At That Point in Time: The Inside Story of the Senate Watergate Committee (1975) — lamenting the missed opportunities to help the GOP, including the fact that both the Democrats and the CIA were well aware a break-in was being planned.

The Ervin Committee is primarily responsible for the portrayal of John Dean as an innocent whistleblower. Dean was the president’s lawyer but had exposed himself to criminal prosecution by running the cover-up. As it collapsed, Dean had sought out career prosecutors, looking for immunity in exchange for testimony against his former colleagues. They refused, believing Dean’s leadership role was too significant to overlook. His well-connected Democrat lawyer, however, succeeded in obtaining immunity from the Senate committee. He became their principal witness, deliberately portrayed as a national hero and fitting perfectly into the Democrat/media narrative. Archibald Cox, the original special prosecutor, even went into court, seeking to condition Dean’s immunity on him not testifying in public, saying the publicity would poison the jury pool. The committee and Chief Judge John Sirica disagreed. After all, it was the publicity that they wanted most.

Dash even met secretly on several occasions with Dean, at his home, to help craft his dramatic testimony. Unlike other witnesses, Dean was not required to submit his opening statement in advance so members and staff could prepare questions, and he was allowed to read its full 240 pages on live television. The committee promptly adjourned upon his completion, preventing any opportunity to challenge or respond to his assertions. No GOP member was willing to pose suggested questions submitted by Nixon’s defense team. Instead, they were read into the record by Sen. Joseph Montoya (D-N.M.), with Dean offering canned responses, clearly prepared in advance.

The media’s saturation coverage of Dean’s testimony contrasts with the near-total lack of coverage when Dean was disbarred the following year: for suborning perjury by others, embezzling campaign funds to pay for his honeymoon, , and authorizing “hush money” payments to the Watergate burglars, including to Howard Hunt, who had helped to plan the break-in. The contents of Hunt’s office safe had been delivered to Dean, who helpfully destroyed documents which Hunt later maintained would have shown his close connections to Dean.

It later developed that Dash also had secretly met with Sirica on numerous occasions and even convinced him to dangle sentence reductions for any defendants cooperating with Ervin Committee investigations. Such ex parte meetings, if known at the time, may well have resulted in Sirica’s disqualification. His “encouragement” of witnesses also conveyed judicial approval of the Ervin Committee and the conduct of its investigations. It was a united front of all three branches of government: the Ervin Committee, the special prosecutors, and Judge Sirica — with the full, enthusiastic support of a monolithic, Nixon-hating media.

The Ervin hearings dominated national news for most of the summer of 1973, and they remain the primary source of public knowledge regarding Watergate. The Committee leaked like a sieve, resulting in massive negative publicity. With Nixon’s people already convicted in the court of public opinion, the hostility in the hearing room was palpable. Unlike an actual trial, the Committee was not required to present its case first, through testimony under oath of witnesses, who were subject to cross-examination by the accused. That had already been accomplished through rumor and innuendo. Nixon’s people were the only ones in the hearing room that were under oath. Because of the publicity, they were fearful of exercising their Fifth Amendment rights not to testify out of concern it would further poison an already biased D.C. jury pool. For their part, special prosecutors postponed any criminal indictments for ten months, while witness after witness was subjected to the Ervin Committee’s legislative “show trial.”

Contrast this with today.

Now: The January 6 Committee

The U.S. House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol was established on July 1, 2021, largely on a party-line vote. The scope of its investigation appears to be incredibly broad: a criminal investigation that, so far, has interviewed over five hundred witnesses. There appears to be no interest in exploring what law enforcement knew in advance of the riot, what role FBI infiltrators may have played, or why the Capitol was left so unprotected. Such questions might complicate the desired narrative. Instead, the Committee seems intent on gathering information far afield from the Capitol Hill riot itself — no doubt to use against any and all Trump supporters in the future.

We don’t know how this will end, but we can expect the Committee to hold extensive public hearings, replete with massive press coverage, and then to recommend the Justice Department initiate criminal investigations — almost as though those weren’t already underway. One legal analyst has already opined that any Fifth Amendment claims by potential witnesses can be used against them in future proceedings.

Neither any of the Committee’s members nor its staff have any intention of defending Trump or his supporters. There’s not a ripple of partisan bickering apparent in any of the proceedings. The two GOP members — Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) and Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) — were selected by Speaker Nancy Pelosi after rejecting GOP leadership nominations for their seven allotted slots. Both voted for Trump’s impeachment and have become “estranged” from most of their Republican colleagues as a result of their committee participation.

This is a situation certain to get worse once public hearings actually begin. While Howard Baker was lionized by the press at the time, it could be argued that his lack of partisan advocacy resulted in Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976 — and that Liz Cheney’s anti-Trump posture could underlie similar GOP losses in 2022 and 2024.

In February of this year, Chief District Judge Beryl Howell publicly urged the Justice Department to promise reduced sentences to riot defendants choosing to cooperate with the Committee — almost an exact parallel to what Chief Judge Sirica did in Watergate. It is not known if she was encouraged to make this announcement by members of the legislative or executive branches, but it has all the appearance of a judicial seal of approval on the January 6 Committee.

While there have been plea bargains for some who entered the Capitol and, after a full year’s delay, several insurrection indictments, federal prosecutors have yet to bring many defendants to trial. As with Watergate, it is almost as though they are deferring prosecutions to the anticipated hearings of the House Select Committee.

All three branches are again united: the January 6 Committee, Merrick Garland’s Justice Department, and Chief Judge Howell — with the full, enthusiastic support of the Trump-hating mainstream media.

GOP commentators reassuringly point out that lingering concerns regarding the January 6 riot don’t show up in public opinion polls, but this was also true of Watergate — at least until the Ervin Committee began its nationally televised hearings, coupled with gavel-to-gavel coverage by the monolithic media. Today, Democrats don’t have the luxury of time: they have to “go public” soon to influence November’s midterms. If they lose control of the House, the January 6 Committee could turn on them and refocus attention on Democratic intelligence and security failures — and decisions made by the Speaker. If they lose in November and I were Nancy Pelosi, I’d resign, too.

The singular and dramatic difference today is the absence of a monolithic media, set on advancing a single, agreed-upon narrative. There is plenty of coverage casting doubt on the legitimacy of the January 6 Committee, as well as on the motives and objectivity of its members. That was certainly not the case with the Ervin Committee. Thank heavens for a free, vibrant, and diverse press!

Watergate legitimized the criminalization of politics, which has continued to this day. To many Americans, we’ve seen the movie on select committees before, and we don’t like the actors, the plot, or the ending.

Read Full Article on ShepardOnWatergate.com