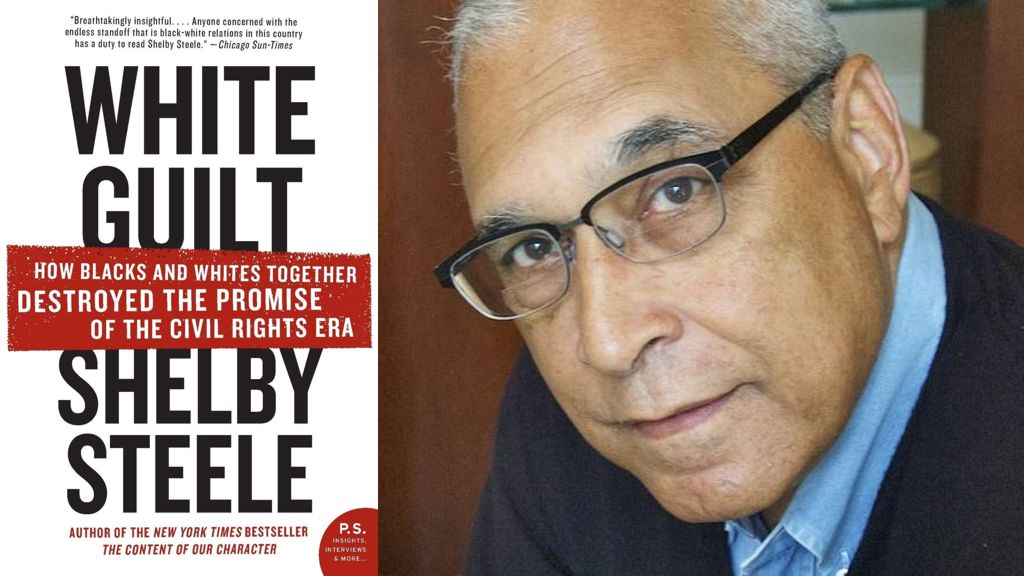

In 1955 the killers of Emmett Till, a black Mississippi youth, were acquitted because they were white. Forty years later, despite the strong DNA evidence against him, accused murderer O. J. Simpson went free after his attorney portrayed him as a victim of racism. The age of white supremacy has given way to an age of white guilt;and neither has been good for African Americans.

Through articulate analysis and engrossing recollections, acclaimed race relations scholar Shelby Steele sounds a powerful call for a new culture of personal responsibility.

Editorial Reviews

Review

“There is no writer who deserves black America’s allegiance more than Shelby Steele… Steele’s writing is a marvel.” ~ John McWhorter, National Review

“Piercing and personal… WHITE GUILT is a brilliant little essay, deserving of a large and appreciative audience.” ~ Washington Times

“Thought provoking.” ~ Library Journal

“Powerful, lucid and elegant…On questions of race in America–white guilt, black opportunism–[Steele] is our 21st century Socrates.” ~ Charles Johnson, author of MIDDLE PASSAGE, National Book Award winner

“ Shelby Steele is America’s clearest thinker about America’s most difficult problem.” ~ George F. Will

“A hard, critical look at affirmative action, self-serving white liberals and self-victimizing black leaders.” ~ Publishers Weekly

“Prophet or polemicist, Steele is a graceful and often compelling literary stylist… [and] deserves a wide readership.” ~ Cleveland Plain Dealer

“As delightful a read as one can find on a book devoted to America’s historically most contentious topic.” ~ New York Post

From Publishers Weekly

Speaking the language of moralism, individual freedom and responsibility, contrarian cultural critic Steele builds on ideas he earlier articulated in his National Book Critics Circle Award–winner The Content of Our Character (1990). Today’s problem, Steele forcefully argues, is not black oppression, but white guilt, a loose term that encompasses both an attempt by whites to regain the moral authority they lost after the Civil Rights Movement, and black contempt toward “Uncle Tom” complicity with white hegemony, resulting in a shirking of personal accountability. Steele makes a passionate case against the “Faustian bargain” he perceives on the left: “we’ll throw you a bone like affirmative action if you’ll just let us reduce you to your race so we can take moral authority for ‘helping’ you.” But progressive readers will object to his assertion that systemic racism is a thing of the past—and to his praise of the Bush administration’s philosophy on poverty, education and race. Though Steele takes a hard, critical look at affirmative action, self-serving white liberals and self-victimizing black leaders, he stops short of offering real-world solutions. (May)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. –This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From Booklist

Steele asserts that the primary focus of the civil-rights era was a legitimate quest to remove racial barriers. In the shift to the black-power era, Steele sees a paradigm shift, away from racial uplift and agency, where blacks assume responsibility for themselves, to a “race is destiny” mode. As the counterculture merged with the civil-rights movement, America was exposed for its racial hypocrisy and, consequently, lost its moral authority. Here, “white guilt” became the moral framework for America. Steele argues that liberal whites embraced guilt for two reasons: to avoid being seen as racists and to embrace a vantage point where they could mete out benefits to disadvantaged blacks through programs such as affirmative action. Steele believes blacks made a deal with the devil by exchanging responsibility and control over their destiny for handouts. He sees a deficiency in black middle-class educational achievement, further raising questions about claims of lack of equal opportunity. Despite these omissions, the cultural analysis of America’s loss of moral authority for its exposed racism has resonance today. Vernon Ford

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved –This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

About the Author

Shelby Steele is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and Stanford University, and is a contributing editor at Harper‘s magazine. His many prizes and honors include the National Book Critics Circle Award, an Emmy Award, a Writers Guild Award, and the National Humanities Medal.–This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From the Back Cover

In 1955 the murderers of Emmett Till, a black Mississippi youth, were acquitted of their crime, undoubtedly because they were white. Forty years later, O. J. Simpson, whom many thought would be charged with murder by virtue of the DNA evidence against him, went free after his attorney portrayed him as a victim of racism. Clearly, a sea change had taken place in American culture, but how had it happened? In this important new work, distinguished race relations scholar Shelby Steele argues that the age of white supremacy has given way to an age of white guilt — and neither has been good for African Americans.

As the civil rights victories of the 1960s dealt a blow to racial discrimination, American institutions started acknowledging their injustices, and white Americans — who held the power in those institutions — began to lose their moral authority. Since then, our governments and universities, eager to reclaim legitimacy and avoid charges of racism, have made a show of taking responsibility for the problems of black Americans. In doing so, Steele asserts, they have only further exploited blacks, viewing them always as victims, never as equals. This phenomenon, which he calls white guilt, is a way for whites to keep up appearances, to feel righteous, and to acquire an easy moral authority — all without addressing the real underlying problems of African Americans. Steele argues that calls for diversity and programs of affirmative action serve only to stigmatize minorities, portraying them not as capable individuals but as people defined by their membership in a group for which exceptions must be made.

Through his articulate analysis and engrossing recollections of the last half-century of American race relations, Steele calls for a new culture of personal responsibility, a commitment to principles that can fill the moral void created by white guilt. White leaders must stop using minorities as a means to establish their moral authority — and black leaders must stop indulging them. As White Guilt eloquently concludes, the alternative is a dangerous ethical relativism that extends beyond race relations into all parts of American life.–This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.