KEY TAKEAWAYS

- With trillions of dollars at stake, bad decisions are inevitable if Congress rushes through a poorly vetted plan to pay for its buffet of new social spending.

- The wealth taxes—cousins of unrealized capital gains taxes—tried in Europe have “frequently failed to meet their redistributive goals.”

- These additional layers of complexity are good news for auditors and accountants, but bad news for businesses.

In ongoing discussions with House Democrats about their ever-evolving plan to expand the role of government in American life, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi reportedly told her members: “There is no bad decision.”

With trillions of dollars at stake, bad decisions are inevitable if Congress rushes through a poorly vetted plan to pay for its buffet of new social spending.

The parade of different taxes that congressional Democratic leaders have put forth in recent weeks demonstrate that Congress is, in fact, deliberating from among a menu of bad decisions.

Last month, the House Ways and Means Committee advanced a plan that contained increased tax rates on corporate income, individual income, and capital gains income. That plan would have given the United States one of the highest business tax rates in the developed world, and everyday Americans would ultimately pay in the form of lower real wages.

Last week, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., firmly rejected the taxes in the House proposal.

With those damaging taxes apparently off the table, Congress quickly turned its focus to what Democrats are referring to as a “wealth tax.”

Only a shell of that plan existed as of last week, but Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., hurriedly pieced together a 107-page proposal, released on Wednesday. The move would fundamentally change taxation in America, arguably more than any other change since the 16th Amendment instituted the income tax.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated that the new tax “would help get at capital gains.” Specifically, the plan would tax unrealized capital gains. As one’s company or assets increase in market value, he or she would pay annual taxes to the IRS on that increase, even though no actual income was received.

The premise of taxing an asset that hasn’t created actual income is especially problematic when most of an individual’s wealth is tied up in a single asset. Without sufficient income from other sources, taxpayers might be forced to sell their asset—or a portion of it—to pay the taxes they owe.

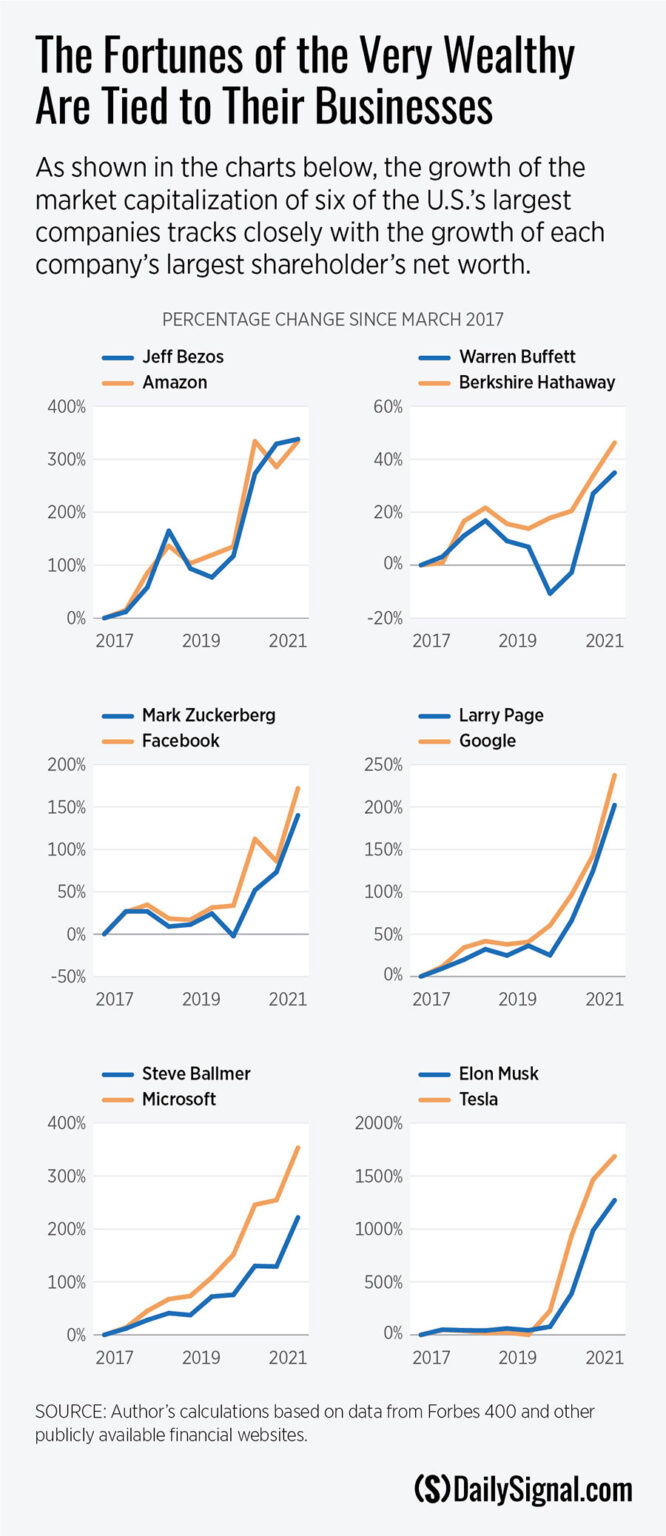

Perhaps counterintuitively, the wealthiest Americans often have 90% or more of their fortunes in a single asset; namely, stock in their business. The vast majority of the wealth of Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Warren Buffett, and Elon Musk is held as stock in Amazon, Facebook, Berkshire Hathaway, and Tesla, respectively. Much of their remaining wealth is invested in other business ventures, like Bezos’ Blue Origin and Musk’s SpaceX.

When a company like Tesla increases in value by fivefold or tenfold in a year, the owner would have little choice but to sell stock to cover the massive tax on the new value.

Even under more typical levels of growth, it’s still unrealistic to think that a billionaire would come up with the money for the tax by “cutting back” on the, say, 2% of his wealth supporting his lifestyle. Rather, the business owner would almost certainly pay the tax out of the 98% of his wealth invested in supporting his or her business.

This outflow of capital is the same mechanism that causes a corporate income tax to ultimately fall on labor through the reduction of real wages. It should come as no surprise, then, that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development observed that the wealth taxes—cousins of unrealized capital gains taxes—tried in Europe have “frequently failed to meet their redistributive goals.”

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development also stated that, with few exceptions, the revenues collected from wealth taxes have been very low. Economist Eric Pichet estimated that the French wealth-tax experiment led to negative revenue effects. French President Emmanuel Macron said that more than 10,000 individuals with 35 billion euros’ worth of assets fled the country to avoid the tax.

Because of the dismal record of wealth taxes (and one constitutional challenge), many European countries such as France, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Iceland, and Finland abandoned their counterproductive wealth taxes in recent years.

Taxes on unrealized capital gains are also enormously burdensome to administer. There’s no easy way to determine the value of many assets on an annual basis. Therefore, legislators face a trade-off: Put in place a complicated, bureaucratic process to measure all assets’ values, or make certain hard-to-value assets tax-exempt until they are sold. The more assets that are exempt, the easier it is for the wealthy to avoid the tax.

Fortunately, a deal involving a tax on unrealized capital gains also appears to be off the table after Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., blasted the “convoluted” tax proposal. However, in its place, congressional Democrats are now floating a different convoluted tax proposal, a corporate profits minimum tax.

The minimum tax involves a 15% tax on large companies’ book income, which is what companies report in their financial statements. It’s troubling that the rules for determining book income are determined by a Connecticut-based nonprofit, the Financial Accounting Standards Board. Effectively, Congress could be handing some of its taxing authority over to a private organization.

Advocates of the new minimum tax justify the tax on the grounds that some corporations “get away with” not paying tax in certain years.

Corporations often pay zero taxes in a year because of losses in that year or because they accrued net operating losses in prior years. Net operating losses are an efficient, desirable feature of a corporate income tax because they help ensure that the tax code is not biased against businesses that suffer periodic losses.

Suppose Company A has $1 million of profit in Year 1 and another $1 million profit in Year 2. Company B, on the other hand, suffers a loss of $10 million in Year 1, followed by a gain of $12 million in Year 2.

Note that both companies have a total profit of $2 million over the two years. If not for the allowance of net operating losses, Company B would have to pay tax on $12 million of profit in Year 2, but would get no tax relief for the losses incurred in Year 1.

Introducing a minimum tax on book income complicates and distorts the net operating losses system. Book income does not factor in net operating losses, introducing a bias in the tax code against loss-making companies, including companies that have a significant one-time investment expense leading to a taxable loss.

Taxpayers with legitimate losses one year may be unable to use net operating losses to offset future gains.

Under the current tax system, when companies do consistently avoid paying taxes, it’s usually because they are able to claim preferential tax credits that are only available to favored businesses or industries.

Unfortunately, there are more than 30 new provisions in the House tax proposal that would expand corporate tax credits.

Minimum taxes are burdensome to administer and comply with, as they effectively represent whole new parallel tax systems.

In addition to the corporate profits minimum tax, Congress is also weighing expansion of another minimum tax system in the international tax code.

These additional layers of complexity are good news for auditors and accountants, but bad news for businesses that want to focus on improving the goods and services they provide.

Congress should reject a new corporate profits minimum tax and the host of other tax proposals that add further layers of complexity on top of an already convoluted tax system.

Lawmakers should say “no” to bad legislation. Instead of heeding Pelosi’s suggestion that there are “no bad decisions,” they should remember the counsel of Hippocrates: First, do no harm.

Read Original Article on Heritage.org

Preston Brashers, Senior Policy Analyst, Tax Policy, Hermann Center

Preston is a senior policy analyst for tax policy in The Heritage Foundation’s Grover M. Hermann Center for the Federal Budget.