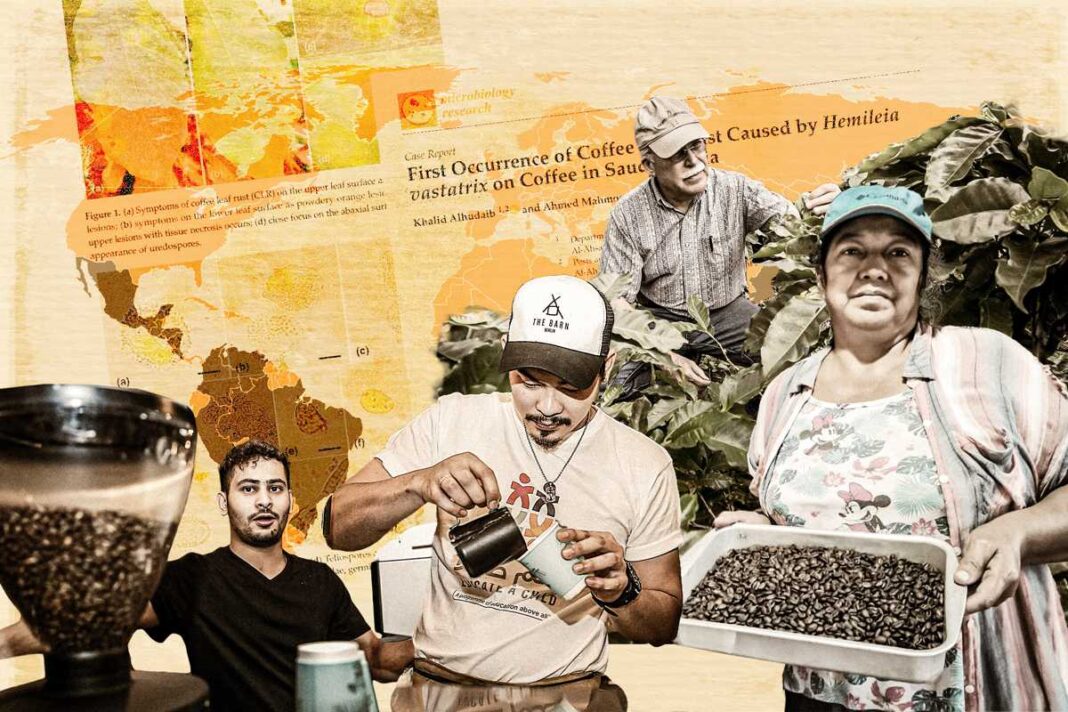

Coffee plantations face threats from bugs, plagues, and genetic fragility—putting America’s annual consumption of 1.6 billion pounds of coffee at risk.

Carmen Alvarez looks down at a five-year-old coffee plant and frowns. She points to the wide brown spots afflicting some of the leaves and says “Ashes are good for [dealing with] the plagues.”

Mrs. Alvarez and her husband Francisco Mamani have been working with coffee plants near Bolivia’s Amboro National Park for 30 years.

In that time, they’ve had their fair share of environmental setbacks.

Coffee has always been a fragile plant that requires specific microclimates to thrive. Controlling fungal diseases and pests are just part of the job.

Most growers within the world’s “coffee belt” nations are well-versed in dealing with these problems—every season brings a different challenge.

As one of the most traded commodities in the world, the global coffee market was valued at $138 billion last year, according to Expert Market Research. FairTrade says the industry employs roughly 125 million people in at least 70 countries.

In the United States, coffee represents 2.2 million jobs and creates more than $100 billion in wage revenue, according to the National Coffee Association.

Mrs. Alvarez said both the wet and dry seasons are becoming less predictable, most noticeably since a few years ago. Consequently, infestations and diseases affecting coffee are now becoming harder to predict and more difficult to mitigate.

The Alvarez family, which runs both a plantation and the coffee roasting company Buenavisteno, isn’t alone.

The increasing struggle to bring in a healthy crop of coffee “cherries” is part of a larger pattern affecting the world’s producers.

As weather and seasons become more erratic, diseases have become more widespread, threatening the future of growers everywhere.

The fungal disease known in the industry as coffee leaf rust is one of the primary blights that affects coffee—particularly the Arabica strains—and spreads like a pathogen.

The dreaded coffee leaf rust was detected for the first time in Saudi Arabia, a country that had harbored one of the few remaining coffee regions free of the disease, according to a study published in January.